Clinical Profiles and Survival Outcomes in Patients with De Novo Metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma – A Real World Analysis from a Tertiary Cancer Centre

Download

Abstract

Background: Lung cancer remains the most common cancer worldwide, accounting for 11.4% of all cancers and 18% of all cancer deaths. The age-adjusted incidence of lung cancer in India shows a rising trend since 1980s (NCDIR). Understanding the clinico-epidemiological profile is crucial to assess the impact of prevention and treatment strategies.

Methods: This study retrospectively analysed patients (>18 years) with de novo metastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) treated at our centre between January 2020 to December 2022. Data on demography, disease profile, treatment and outcomes were analysed, and survival analysis done using Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression models.

Results: Total 358 patients were analysed. Mean age at diagnosis was 52 (range 24-81) years with male preponderance (77%) and 55% had history of tobacco use. Adenocarcinoma was the predominant histology (79%). Common driver mutations seen were EGFR mutation (25%; MC are EGFR exon 19 deletion and L858R point mutation), ALK gene rearrangement (4%), and ROS1 mutation (<1%). Targetted therapy with TKI was used alone in 108 patients and in combination with chemotherapy in 58 patients (total 166). The remaining 192 patients received chemotherapy alone. Response evaluation data available for 205 patients with overall response (CR+PR), disease control (CR+PR+SD) and disease progression (PD) rate were 44%, 73% and 27% respectively. With median follow-up of 37 (range 24-48) months, median progression free survival (mPFS) and overall survival (mOS) were 14 and 21 months, respectively. One- and two-year PFS rates were 42% and 10%, while OS rates were 58% and 22%, respectively. Cox-regression analysis revealed histology (Adenocarcinoma vs. SCC; p<0.001) and treatment plan (TKI alone vs. Chemo + TKI; p=.009) as key prognostic factors for disease progression. SCC was associated with a 42% increased hazard (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43-0.78) of progression. Median overall survival with TKI alone, chemotherapy alone and TKI plus chemotherapy were 21, 18 and 15 months, respectively (p=.789). Tobacco use showed a trend towards worse survival (p=0.071).

Conclusions: This study highlights evolving care of NSCLC in Northeast India, emphasising importance of tobacco control measures in view of trend towards worse survival in tobacco users, broader molecular testing, and improved access to targeted therapies.

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, accounting for approximately 1.8 million deaths annually and representing 18% of all cancer mortalities worldwide [1]. Among all cancer types, it holds the distinction of being both the most frequently diagnosed and the most lethal. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, lung cancer constituted 11.4% of new cancer cases globally, underscoring its significant public health burden [1]. In India, the age-adjusted incidence rate of lung cancer has been steadily increasing since the 1980s, particularly among males, with a growing trend also observed in females, likely due to changing patterns in tobacco use, environmental pollution, and occupational exposure [2].

Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of all lung cancers and includes histological subtypes such as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and large cell carcinoma [3]. De novo metastatic NSCLC, defined as stage IV disease at initial diagnosis, is the most common presentation, primarily due to its insidious onset and lack of specific early symptoms. At this stage, curative intent treatment is typically not feasible, and therapy is focused on prolonging survival and maintaining quality of life [4].

In recent years, major advances in the molecular characterization of NSCLC have transformed its management. Identification of driver mutations such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangements, and ROS1 (ROS proto-oncogene) fusions has enabled the use of targeted therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which have significantly improved outcomes in selected patients [5-7]. Additionally, immune checkpoint inhibitors have emerged as a viable option, particularly in patients with high PD-L1 expression and no actionable mutations [4, 8]. Despite these advances, overall survival in de novo metastatic NSCLC remains suboptimal and varies significantly depending on patient factors, tumor biology, and treatment access [9].

Understanding the clinico-epidemiological profile of patients with metastatic NSCLC is essential to guide public health interventions, enhance early detection, and optimize individualized treatment. In India, especially in the North-Eastern region, limited data exist on the real-world presentation, molecular profile, treatment strategies, and survival outcomes of NSCLC [10]. The population in this region is diverse, with unique genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors that may influence disease behavior and therapeutic response. Tobacco use remains high, particularly in the form of smokeless tobacco and beedis, and access to advanced diagnostics and targeted therapies may be limited due to economic constraints and healthcare disparities [2, 10].

This study aims to fill this knowledge gap by evaluating the clinical profiles, molecular characteristics, treatment patterns, and survival outcomes of patients diagnosed with de novo metastatic NSCLC in a tertiary cancer center in Northeast India. It also seeks to identify prognostic factors associated with disease progression and overall survival, providing evidence to inform regional policy, improve access to molecular testing, and support tobacco control initiatives.

Through this retrospective analysis, we aim to contribute valuable insights into the evolving landscape of lung cancer care in a low-resource, high-burden setting, where challenges in infrastructure, awareness, and treatment accessibility persist. The findings are expected to highlight the critical need for equitable healthcare delivery and the integration of precision oncology into routine practice, ultimately improving outcomes for patients with advanced NSCLC.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a retrospective observational study conducted at Dr. B Borooah Cancer Institute, a tertiary cancer center in Northeast India. The study aimed to evaluate the clinical characteristics, molecular profile, treatment patterns, and survival outcomes in patients diagnosed with de novo metastatic NSCLC. The data were collected from the institutional hospital registry and electronic medical records. The study received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Study Population

The study included all consecutive adult patients (≥18 years) diagnosed with de novo stage IV NSCLC between January 2020 and December 2022. Patients were included if they had histologically or cytologically confirmed NSCLC, radiologically measurable metastatic disease at diagnosis, and had received at least one line of systemic treatment at the study center. Patients with small cell lung cancer, mixed histology, or those with incomplete records (e.g. pathology or survival data) were excluded.

Data Collection

Demographic and clinical data including age at diagnosis, gender, smoking history, performance status, histological subtype, metastatic sites, and comorbidities were extracted. Performance status was assessed using Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) criteria. Tumor characteristics such as histology (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or NSCLC-not otherwise specified) and molecular profile (EGFR, ALK, ROS1 mutations/fusions) were recorded. Molecular testing was performed using PCR-based assays for EGFR mutations and immunohistochemistry (IHC) followed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for ALK and ROS1 rearrangements as per availability. PDL1 status was not routinely done for patients due to the lower and middle income nature of the population and non affordability for the checkpoint inhibitors.

Treatment data included the type of systemic therapy received in the first line (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or a combination), use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), number of chemotherapy cycles, and radiotherapy details (if any). Response evaluation was done using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 guidelines based on available imaging reports.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes were progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Secondary outcomes included response rates [complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD)], disease control rate (DCR = CR + PR + SD), and factors associated with survival outcomes.

PFS was defined as the duration from the start of treatment to the date of documented disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurred earlier. OS was calculated from the date of diagnosis until death from any cause or last follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges, as appropriate.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to estimate median PFS and OS, and log-rank tests were used to compare survival curves between groups. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to identify independent prognostic factors for disease progression and death. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Variables with a p-value <0.05 in univariate analysis were considered significant, and included in multivariate models.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM Corp), and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

As depicted in Table 1, a total of 358 patients with de novo metastatic NSCLC were included in the analysis.

| Mean age | 52 year (24 - 81 years) |

| Gender: | n (%) |

| Male | 276 (77) |

| Female | 82 (23) |

| History of smoking | 197 (55) |

| HPE: | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 283 (79) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 61 (17) |

| NSCLC-NOS | 14 (4) |

| ECOG-PS | |

| 0-1 | 243 (68) |

| ≥2 | 115 (32) |

| Metastatic sites | |

| Bone | 165 (46) |

| Brain | 64 (18) |

| Pleura | 75 (21) |

| Adrenal gland | 57 (16) |

| Liver and | 42 (12) |

| Contralateral lung | 50 (14) |

| Metastatic disease: | |

| Single site metastasis | 186 (52) |

| Multiple site metastases | 172 (48) |

The mean age at diagnosis was 52 years (range: 24–81), with the majority being male (n=276, 77%) and 55% (n=197) reporting a history of tobacco use, predominantly in the form of smoking bidis or cigarettes.

Histologically, adenocarcinoma was the most prevalent subtype, seen in 79% (n=283) of cases, followed by squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in 17% (n=61), and poorly differentiated NSCLC-not otherwise specified (NSCLC-NOS) in 4% (n=14). Performance status at diagnosis was good (ECOG 0-1) in 68% of patients, while 32% presented with ECOG ≥2. Comorbidity data were not uniformly available and were therefore not analysed. Common metastatic sites at presentation included bone (46%), brain (18%), pleura (21%), adrenal gland (16%), liver (12%), and contralateral lung (14%). Multiple metastatic sites were present in 48% of patients at the time of diagnosis.

3.2 Molecular Profile and Targetable Mutations

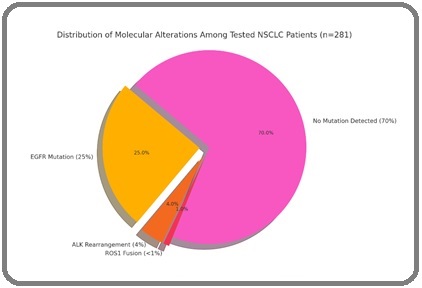

Of the 358 patients, 281 (79%) underwent molecular testing. EGFR mutations were identified in 90 patients (25%), with exon 19 deletion (58%) and L858R point mutation (42%) being the most common. ALK gene rearrangements were seen in 14 patients (4%), and ROS1 fusions were identified in only three patients (<1%). PD-L1 testing was not routinely performed due to logistical limitations during the study period (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of Molecular Alterations among Tested NSCLC Patient (n=281).

3.3 Treatment Patterns

Among all patients, 108 (30%) received targeted therapy with TKIs as first-line treatment, either due to confirmed actionable mutations or clinical judgment in highly probable cases pending testing results. The remaining 250 patients (70%) received platinum-based doublet chemotherapy, most commonly paclitaxel or pemetrexed with platinum (carboplatin/cisplatin).

Of the chemotherapy group, 192 patients received chemotherapy alone, while 58 received chemotherapy followed by or combined with targeted therapy (TKI) based on mutation confirmation post-initiation.

Radiotherapy was used selectively for symptomatic metastases, particularly brain and bone lesions.

3.4 Response Rates

Response evaluation data (RECIST 1.1) were available for 205 patients. The overall response rate (ORR; complete response plus partial response) was 44%, with a disease control rate (DCR; complete response plus partial response plus stable disease) of 73%. Disease progression at first evaluation (most commonly done at 3months of treatment initiation) was observed in 27% of these patients.

In subgroup analysis, patients receiving TKI alone had a higher ORR (55%) and DCR (81%) compared to those receiving chemotherapy alone (ORR 41%, DCR 68%) (p=0.043). Amongst patients who received TKI, patients with ALK-positive disease showed the highest DCR (although numbers were small, n=14).

3.5 Survival Outcomes

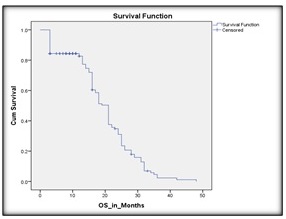

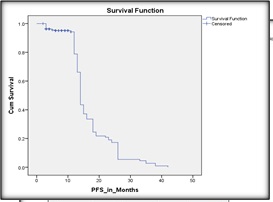

The median follow-up duration was 37 months (range: 24 – 48 months). The median progression-free survival (mPFS) for the entire cohort was 14 months, and the median overall survival (mOS) was 21 months, CI 95% (as depicted in Figures 2 and 3)

Figure 2. Kaplan Meier Curve Demonstrating the Overall Survival in the Study Population.

Figure 3. Kaplan Meier Curve Demonstrating the Progression Free Survival in the Study Population.

The 1-year PFS and OS rates were 42% and 58%, respectively. The 2-year PFS and OS rates dropped to 10% and 22%, respectively, reflecting disease progression and limited long-term control.

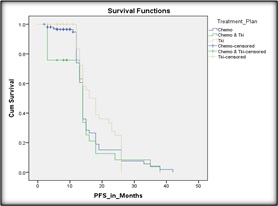

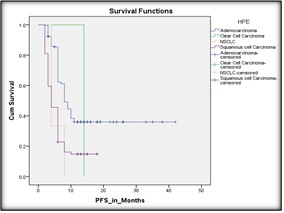

Survival analyses when done as per treatment plans showed the following pattern: TKI with chemotherapy, chemotherapy alone and TKI alone has OS of 15, 18 and 21 months, respectively which was statistically significant (p=0.002). Median PFS followed a similar trend, TKI with chemotherapy, chemotherapy alone and TKI alone showed PFS of 10, 12 and 17 months respectively (p= 0.041) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Kaplan Meier Curve Depicting the PFS as per Treatment Plan.

3.6. Prognostic Factors

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with disease progression and overall survival (as shown Table 2).

| Variables | Months | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| PFS | Smoker | 13 | 1.112 (0.874 – 1.416) | 0.372 |

| Non-smoker | 15 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 19 | 0.580 (0.430 – 0.783) | <0.001 | |

| Squamous cell ca | 14 | |||

| TKI alone | 17 | 0.841 (0.338 – 2.092) | 0.009 | |

| Chemotherapy | 12 | |||

| TKI- chemotherapy | 10 | |||

| OS | Smoker | 16 | 1.301 (0.978 -1.730) | 0.071 |

| Non-smoker | 21 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 20 | 0.905 (0.674 – 1.215) | 0.487 | |

| Squamous cell ca | 18 | |||

| TKI alone | 21 | 0.944 (0.615 – 1.448) | 0.789 | |

| Chemotherapy | 18 | |||

| TKI- chemotherapy | 15 |

Multivariable analysis of PFS and OS showed that type of treatment i.e., TKI vs TKI with chemotherapy (as shown in Figure 4 and Table 2) and histology i.e., SCC vs adenocarcinoma (as shown in Figure 5 and Table 2) showed a statistically significant correlation with PFS. However no variable showed a statistically significant correlation with OS.

Figure 5. Kaplan Meier Curve Demonstrating the Progression Free Survival as Per Histology.

Survival analysis by mutational profile was not done as not enough patients had been tested for same.

3.6.1. Type of treatment also has significant impact on progression free survival:

Patients receiving TKI alone had better survival outcomes than those receiving chemotherapy ± TKI (HR: 0.841, 95% CI 0.338 – 2.092, p=0.009) (as shown in Figure 4).

3.6.2. Histology was significantly associated with progression-free survival:

Patients with SCC had a 42% higher hazard of progression compared to those with adenocarcinoma (HR 0.58; 95% CI: 0.43–0.78; p<0.001) (as shown in Figure 5).

4. Discussion

This retrospective study provides a comprehensive overview of the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and survival outcomes of patients diagnosed with de novo metastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) in Northeast India. Our findings highlight important trends relevant to regional cancer control and resource-adapted treatment strategies in real-world practice.

4.1. Demographic and Clinical Features

The mean age at diagnosis (52 years) in our cohort is substantially lower than typical Western/global NSCLC cohorts (60–70 years) and aligns with recent Indian “young-onset” lung cancer series reporting a median overall survival ~26 months with a high prevalence of oncogenic drivers in younger patients [11]. The younger age may reflect earlier tobacco exposure, indoor biomass fuel exposure, and environmental pollutants in this region [12]. The marked male predominance (77%) and high prevalence of tobacco use (55%) further support tobacco smoking as a key etiological factor, although smokeless forms of tobacco may also contribute in this region [3].

Adenocarcinoma emerged as the most common histology (79%), in line with the global shift from squamous to glandular subtypes due to changes in smoking patterns and improvements in histological classification [4,5]. This predominance also correlates with the higher detection of driver mutations in adenocarcinoma, which allows for targeted therapy use.

4.2. Molecular Testing and Targetable Mutations

Molecular testing for EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 mutations was performed in 79% of patients. EGFR mutations were observed in 25% of tested patients, with the majority harboring exon 19 deletions or L858R mutations. This mutation rate aligns with other Indian data (20–35%) and highlights the need to implement universal mutation testing at diagnosis [6, 7].

ALK rearrangements were identified in 4% and ROS1 fusions in <1% of patients, figures that are consistent with global averages [8]. However, PD-L1 testing was not routinely performed during the study period due to logistic and financial constraints, limiting the use of immunotherapy in our cohort. These findings stress the importance of strengthening diagnostic infrastructure to facilitate broader biomarker-based treatment decisions. Current guidance emphasizes reflex biomarker testing, including PD-L1 and broader next-generation sequencing (NGS), to minimize delays and expand access to matched therapies [13, 14].

4.3. Treatment Patterns and Response

In terms of therapy, 30% of patients received first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), either alone or after a brief course of chemotherapy, while the majority received platinum-based doublet chemotherapy. Targeted therapy showed better response rates and disease control compared to chemotherapy, reaffirming its role in driver mutation- positive patients [9]. However, a significant proportion of patients could not access timely molecular testing or targeted agents, possibly due to delayed referrals, high out-of-pocket costs, or limited drug availability.

The overall response rate (44%) and disease control rate (73%) in our cohort are comparable to other real-world studies, reflecting the benefits of systemic therapy even in advanced-stage disease [10]. Patients receiving TKIs alone achieved higher response rates, with longer progression- free and overall survival, emphasizing the importance of timely mutation profiling and access to targeted agents.

4.4. Survival Outcomes

With a median follow-up of 37 months, the median progression-free survival (mPFS) for the entire cohort is 14 and median overall survival (mOS) is 21 months, respectively. These figures compare favorably to historical data for metastatic NSCLC, where mOS was <12 months before the advent of targeted therapies [15]. One- and two- year OS rates (58% and 22%) as seen in our study also reflect the benefits of molecularly guided therapy, even in a resource-limited setting.

Subgroup analysis revealed a clear survival advantage in patients receiving TKI monotherapy (mOS 21 months) compared to those receiving chemotherapy alone (18 months) or combined therapy (15 months). Interestingly, the TKI plus chemotherapy group had worse outcomes, possibly due to selection bias (e.g., rapidly progressive disease or delayed mutation confirmation). These findings align with prior clinical trials and real-world registries demonstrating superior survival in EGFR/ALK-mutant NSCLC when appropriately treated [16].

Squamous histology was associated with worse prognosis (HR 0.58, CI 0.430 – 0.783), likely reflecting both the biology of the disease and the absence of actionable mutations in most cases [17]. Smoking history also independently predicted poorer outcomes, supporting existing literature on the adverse impact of tobacco on treatment response and progression [18].

4.5. Regional Implications and Challenges

This study sheds light on the evolving landscape of NSCLC management in Northeast India. Despite challenges in infrastructure, socioeconomic barriers, and diagnostic limitations, the incorporation of molecular testing and targeted therapy has begun to reshape outcomes in this high-burden region. However, large gaps remain in equitable access to care.

The relatively younger age at diagnosis underscores the need for earlier screening and tobacco cessation initiatives. Public health efforts should prioritize awareness campaigns, access to low-dose CT screening in high-risk individuals, and integration of molecular diagnostics into public sector oncology services.

Additionally, the lack of immunotherapy in this cohort highlights a critical unmet need. While PD-L1 testing and checkpoint inhibitors are standard in Western practice, their high cost limits use in many Indian settings. Strategies such as tiered pricing, generic manufacturing, and inclusion in government schemes may help bridge this gap. Limited immunotherapy use during our study window reflects access and testing constraints; however, the therapeutic landscape continues to broaden rapidly with multiple approvals between 2021 and 2024, suggesting future cohorts may benefit further as access improves [12].

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is the large, single- institution dataset with uniform data capture and a relatively long follow-up. The inclusion of molecular profiling and survival analysis adds clinical depth and relevance.

However, the study has limitations. As a retrospective analysis, it is subject to selection bias and missing data. Not all patients underwent comprehensive molecular testing or regular imaging follow-up, and immunotherapy use could not be evaluated. Socioeconomic factors and comorbidity data were also not uniformly captured, limiting multivariable risk adjustment.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable real- world insights into the clinical and molecular profile, treatment approaches, and survival outcomes of patients with de novo metastatic NSCLC in Northeast India. The predominance of adenocarcinoma and high prevalence of EGFR mutations emphasize the need for routine molecular profiling at diagnosis to guide therapy. Patients receiving targeted therapy had significantly improved survival compared to those treated with chemotherapy alone, underscoring the importance of early and equitable access to TKI based therapy. There is a need for targeted public health interventions, including tobacco cessation and early detection strategies.

Overall, this study highlights the evolving landscape of NSCLC care in India and advocates for broader implementation of molecular diagnostics, access to targeted agents, and stronger tobacco control policies. Further prospective studies with comprehensive biomarker analysis and inclusion of immunotherapy are warranted to optimize outcomes for lung cancer patients in low- and middle-income countries.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Department of Medical Oncology for their support in data retrieval. Special thanks to the patients and their families whose clinical journeys contributed to this analysis.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate:

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Dr. B Borooah Cancer Institute (BBCI- TMC/Misc-01/MEC/294/2025). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for informed consent was waived. All procedures performed were in accordance with institutional and national ethical standards. All data was anonymized to ensure privacy of participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PSR and KM conceptualized the study. KM contributed to data collection. KM performed the statistical analysis. PSR and KM drafted the manuscript. PSR supervised the manuscript finalization process. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the final version.

References

- Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL , Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2021;71(3). CrossRef

- Indian Council of Medical Research, National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research (ICMR-NCDIR). National Cancer Registry Programme Report 2020. Bengaluru: ICMR-NCDIR 2020.

- The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer Herbst RS , Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. Nature.2018;553(7689). CrossRef

- NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2021 Ettinger DS , Wood DE , Aisner DL , Akerley W, Bauman JR , Bharat A, Bruno DS , et al . Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN.2021;19(3). CrossRef

- Adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage non–small-cell lung cancer Araujo LH , Horn L. Clin Lung Cancer. 2016;17(1):1–5..2016;17(1).

- Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma Mok TS , Wu Y, Thongprasert S, Yang C, Chu D, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, et al . The New England Journal of Medicine.2009;361(10). CrossRef

- Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Peters S, Camidge DR , Shaw AT , Gadgeel S, Ahn JS , Kim D, Ou SI , et al . The New England Journal of Medicine.2017;377(9). CrossRef

- New and emerging targeted treatments in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer Hirsch FR , Suda K, Wiens J, Bunn PA . Lancet (London, England).2016;388(10048). CrossRef

- Therapy for Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Without Driver Alterations: ASCO and OH (CCO) Joint Guideline Update Hanna NH , Schneider BJ , Temin S, Baker S, Brahmer J, Ellis PM , Gaspar LE , et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2020;38(14). CrossRef

- Real-world scenario of lung cancer management in North India: A single-center experience Arora G, Saini R, Gill M, Yadav P, Ghoshal S, Bahl A. South Asian J Cancer.2021;10(2):103-7.

- A profile of lung cancer in the young population with a highlight on the Indian perspective Tansir G, Sharma A, Khurana S, Pushpam D, Malik PS . Frontiers in Oncology.2025;15. CrossRef

- Real-World Survival Outcomes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The Impact of Genomic Testing and Targeted Therapies in a Latin American Middle-Income Country Hernandez-Martinez J, Guijosa A, Flores-Estrada D, Cruz-Rico G, Turcott J, Hernández-Pedro N, Caballé-Perez E, Cardona AF , Arrieta O. JCO global oncology.2024;10. CrossRef

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 4.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Riely GJ , Wood DE , Ettinger DS , Aisner DL , Akerley W, Bauman JR , Bharat A, et al . Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN.2024;22(4). CrossRef

- Expert Consensus on Diagnosis and Molecular Testing Strategies for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in India Biswas B, Pai T, Raut N, Narasimhamurthy VM , Kulkarni B, Singh A, Pasricha S, Deshmukh J, Limaye S. Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology.2025. CrossRef

- The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ , Meza R, Kong CY , Cronin KA , Mariotto AB , Lowy DR , Feuer EJ . The New England Journal of Medicine.2020;383(7). CrossRef

- Osimertinib or Platinum-Pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-Positive Lung Cancer Mok TS , Wu Y, Ahn M, Garassino MC , Kim HR , Ramalingam SS , Shepherd DA , et al . The New England Journal of Medicine.2017;376(7). CrossRef

- Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer Scagliotti GV , Parikh P, Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, Serwatowski P, et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2008;26(21). CrossRef

- Lung cancer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-- incidence and predicting factors Torres JP , Marín JM , Casanova C, Cote C, Carrizo S, Cordoba-Lanus E, Baz-Dávila R, et al . American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.2011;184(8). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Nursing , 2026

Author Details

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times