Efficacy of Psychosocial Interventions for Managing Anxiety and Depression in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

Download

Abstract

Objective: To systematically review and synthesize the current evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for managing anxiety and depression in adult patients with cancer.

Methods: A systematic search of electronic databases was conducted to identify relevant RCTs published from 2020 onwards. Studies that assessed the impact of a psychosocial intervention compared to a control condition on anxiety and/or depression outcomes in adult cancer patients were included. Two reviewers independently screened records, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool. Data on study characteristics, interventions, and outcomes were synthesized narratively.

Results: Thirty-nine RCTs were included. The most frequently evaluated interventions were Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs), and cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM). The majority of studies demonstrated that these interventions led to statistically significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety and depression compared to control conditions. CBT was the most consistently effective modality across diverse cultural settings. The analysis of intervention duration indicated that brief, structured programs (4-8 weeks) could be highly effective, while medium-term interventions (12-16 weeks) provided the most consistent evidence of efficacy. The overall body of evidence was deemed to be of reasonably high quality, with a low risk of bias in most included studies.

Conclusion: Psychosocial interventions, particularly CBT, MBIs, and CBSM, are effective for reducing anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients. The findings support the integration of these interventions, including shorter, structured protocols, into standard oncology care to address the significant psychological burden of cancer. Future research should focus on personalizing interventions and optimizing their delivery for broader implementation.

Introduction

Cancer remains one of the most significant health challenges worldwide, with increasing incidence rates across various populations. According to recent global estimates, cancer accounted for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020, making it a leading cause of mortality and morbidity globally [1]. While advances in detection and treatment have substantially improved survival rates, the cancer experience extends far beyond physical health concerns to encompass profound psychological implications that significantly affect patients’ quality of life and treatment outcomes.

The diagnosis of cancer and subsequent treatment trajectory typically trigger substantial psychological distress, characterized by feelings of vulnerability, fear, uncertainty, and loss of control [2]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines distress as “a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological, social, and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment” [3]. This distress exists on a continuum, ranging from normal feelings of sadness and fear to severe conditions that meet diagnostic criteria for anxiety, depression, and adjustment disorders. The prevalence of clinically significant distress in cancer populations is remarkably high, with studies indicating that approximately 30-50% of patients experience substantial psychological distress at some point during their cancer journey [4]. This distress is not merely an emotional reaction but has tangible clinical implications. Research has consistently demonstrated that unmanaged psychological distress can lead to reduced adherence to treatment regimens, impaired immune function, prolonged hospitalization, poorer quality of life, and potentially worse survival outcomes [5, 6]. The physiological mechanisms underlying these relationships involve complex pathways, including dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and increased systemic inflammation, which can potentially influence disease progression [7].

Recognizing the clinical significance of distress management, leading oncology organizations now recommend routine distress screening as an essential component of quality cancer care. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and NCCN have established guidelines that position distress as the “sixth vital sign” in cancer care, emphasizing the importance of systematic assessment and intervention [8]. This paradigm shift reflects the growing understanding that comprehensive cancer care must address both physical and psychological aspects of the disease.

In response to this recognized need, psychosocial interventions have emerged as evidence-based approaches to mitigate psychological morbidity in cancer patients. These structured interventions aim to enhance patients’ coping skills, improve emotional regulation, foster a sense of mastery, and strengthen social support system [9]. The spectrum of available interventions is diverse, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness- based stress reduction, supportive-expressive therapy, psychoeducational approaches, and counseling services. These interventions share the common goal of helping patients adapt to the challenges of their illness and maintain psychological well-being throughout their cancer journey.

Over the past three decades, substantial research has been dedicated to evaluating the efficacy of psychosocial interventions in oncology settings. Numerous randomized controlled trials and several meta-analyses have demonstrated beneficial effects of these interventions on reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression, improving coping skills, and enhancing overall quality of life [10, 11]. However, despite this accumulated evidence, several important questions remain unanswered. The literature continues to show considerable heterogeneity in effect sizes across studies, and findings regarding the sustainability of benefits and the specific intervention components most responsible for change remain inconsistent.

This variability in research outcomes can be attributed to several factors, including differences in patient populations (cancer type, stage, time since diagnosis), intervention characteristics (modality, duration, intensity, delivery format), methodological quality of primary studies, and outcome measures used to assess distress [12]. Furthermore, there is increasing recognition that a “one-size-fits-all” approach may not be appropriate for psychosocial care in oncology, and that intervention efficacy may vary based on specific patient characteristics and clinical circumstances.

The current state of evidence reveals a critical knowledge gap. While the general value of psychosocial care is increasingly acknowledged, a precise, updated, and methodologically rigorous synthesis is required to determine the overall efficacy of these interventions and to identify the specific conditions and populations most likely to benefit. Previous systematic reviews have often focused on specific types of interventions or particular cancer populations, leaving a need for a comprehensive evaluation of the broader field of psychosocial oncology interventions.

Therefore, this systematic review aims to synthesize the available evidence from randomized controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy of psychosocial interventions in reducing distress in adult cancer patients. A secondary objective is to explore potential moderators of efficacy intervention type. By addressing these questions, this review seeks to provide clinicians, researchers, and policymakers with a current and comprehensive evidence base to guide clinical practice and future research directions in psychosocial oncology.

Methods

Study Design

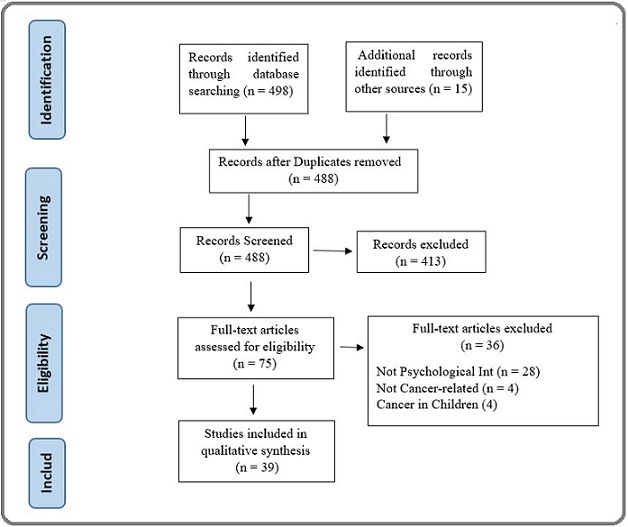

This study will employ a systematic review methodology, conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram for Document Selection.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive and systematic literature search will be performed across multiple electronic databases from 2020 to 2025. The databases include: PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane, PsycINFO and CINAHL.

The search strategy will utilize a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text words related to three key concepts: (1) cancer population, (2) psychosocial interventions, and (3) distress outcomes. The Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” will be used to combine these concepts. The PubMed search strategy is presented in Table 1 and will be adapted for syntax and subject headings specific to each database.

| Database Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. |

| Key words |

| ("Neoplasms"[Mesh] OR "Cancer" OR "Oncology" OR "Tumor" OR "Malignancy") AND ("Psychosocial Intervention"[Mesh] OR "Psychosocial Support Systems"[Mesh] OR "Psychotherapy"[Mesh] OR "Counseling"[Mesh] OR "Mind-Body Therapies"[Mesh] OR "Social Support" OR "psychoeducation" OR "support group") AND ("Distress" OR "Psychological Distress"[Mesh] OR "Anxiety"[Mesh] OR "Depression"[Mesh] OR "Emotional Adjustment" OR "Quality of Life"[Mesh]) AND ("Randomized Controlled Trial" [Publication Type] OR "Clinical Trial" [Publication Type] OR "randomized" OR "RCT" OR "controlled trial") |

Eligibility Criteria

Studies will be selected according to the following PICOS framework:

Population: Adult patients (≥18 years) with any cancer diagnosis, at any stage of the disease trajectory.

Studies focusing exclusively on caregivers or pediatric populations will be excluded.

Intervention: Structured psychosocial interventions of any duration or format (individual, group, or technology- delivered). These include but are not limited to: cognitive- behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based interventions, supportive-expressive therapy, psychoeducation, and counseling.

Comparator: Usual care, wait-list control, attention control, or other active interventions.

Outcomes: Primary outcome: distress as measured by validated scales (e.g., Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Distress Thermometer, Profile of Mood States). Secondary outcomes include anxiety and depression.

Study Design

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in peer-reviewed journals. Non-randomized studies, case reports, conference abstracts, and qualitative studies will be excluded.

Study Selection Process

The study selection will involve two phases:

1. Title and Abstract Screening: Two reviewers will independently screen all retrieved citations against the eligibility criteria.

2. Full-Text Review: Potentially relevant studies will undergo full-text assessment by two independent reviewers.

Disagreements at any stage will be resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. The study selection process will be documented using a PRISMA flow diagram [13].

Data Extraction

Two reviewers will independently extract data using a standardized, piloted data extraction form. The extracted data will include (Table 2):

| Author | Year | Country | Follow- up Week | Sample size_ Int | Sample size_ Con | Age mean | Age SD | Int_Type | Outcome Measure Anx | Effect Size | P- Value | Outcome Measure Deep | Effect Size | P- Value |

| Xia [14] | 2025 | USA | 12 | 64 | 64 | 62.9 | 8.3 | CBSM | SAS | * | 0.003 | SDS | * | 0.015 |

| Zhang [15] | 2025 | Malaysia | 12 | 52 | 51 | 25.6 | 5.6 | MBIs | HADS A | * | 0.001 | HADS D | * | 0.001 |

| Tschenett [16] | 2025 | UK | 8 | 14 | 16 | 62.68 | 7.07 | MBIs | HADS A | 0.11 | 0.01 | HADS D | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Abbas [17] | 2025 | Saudi Arabia | 16 | 30 | 30 | 47.51 | 12.36 | CBT | DAS | 0.0797 | 0.001 | DASS | 0.0865 | 0.001 |

| Tao [18] | 2025 | China | 8 | 80 | 80 | 47 | 15.67 | CBGT | SAS | * | 0.01 | DASS | * | 0.01 |

| Sohl [19] | 2025 | USA | 14 | 23 | 21 | 58.5 | 11.7 | YST | SAS | * | * | PROMIS | * | 0.3 |

| Holtmaat [20] | 2025 | Netherlands | 24 | 57 | 57 | 59 | 32 | MCGP | HADS | * | * | HADS | -1.18 | 0.005 |

| Soleymani [21] | 2025 | Iran | 8 | 15 | 15 | 42.53 | 8.24 | MICBT | DASS-21 | 0.361 | 0.002 | DASS-21 | 0.29 | 0.001 |

| Phiri [22] | 2025 | Malawi | 12 | 59 | 59 | 34.25 | 9.03 | CBT | GAD-7 | 0.59 | 0.002 | PHQ-7 | 0.4 | 0.038 |

| Badaghi [23] | 2025 | Netherlands | 8 | 57 | 54 | 52.6 | 11.4 | eMBCT | * | * | * | HADS‐D | 0.38 | 0.01 |

| Milbury [24] | 2025 | USA | 12 | 50 | 50 | 42 | 5.1 | CBT | HADS- A | * | 0.07 | HADS‐D | * | 0.3 |

| Mi [25] | 2024 | Japan | 12 | 72 | 73 | 53.5 | 21.3 | MM | SAS | * | 0.03 | * | * | * |

| Hao [26] | 2024 | china | 8 | 92 | 92 | 52.9 | 10.5 | CBSM | HADS A | 2.7 | 0.007 | HADS D | * | 0.015 |

| Huang [27] | 2024 | China | 12 | 108 | 108 | 58.62 | 6.69 | PICFHE | SAS | * | 0.001 | SDS | * | 0.001 |

| Chen [28] | 2024 | China | 4 | 140 | 140 | 68.2 | 6.7 | CST | HADS‐A | * | 0.021 | HADS‐D | * | 0.003 |

| Can [29] | 2024 | China | 4 | 51 | 52 | 45.17 | 7.59 | MBSR | HADS‐A | 1.26 | 0.001 | HADS‐D | 1.03 | 0.001 |

| Mosher [30] | 2024 | USA | 6 | 33 | 22 | 70.6 | 9 | MEAN ING | GAD-7 | * | 0.07 | * | * | * |

| Czech [31] | 2024 | Poland | 8 | 17 | 16 | 56.68 | 11.26 | CBT | HADS-M | 0.24 | 0.001 | HADS-M | 0.19 | 0.001 |

| Abd Wahid [32] | 2025 | Malaysia | 12 | 37 | 33 | 51 | 8.8 | G-CBT | * | * | * | PHQ-9 | 0.75 | 0.0001 |

| Marco [33] | 2024 | Spain | 8 | 35 | 41 | 52.5 | 7.03 | CBSM | OASIS | 0.13 | 0.41 | ODSIS | 0.17 | 0.28 |

| Wang [34] | 2024 | China | 8 | 39 | 39 | 62.5 | 8.6 | CBT | SAI | * | 0.001 | * | * | * |

| Koizumi [35] | 2023 | Japan | 4 | 37 | 37 | 35.6 | 0.5 | O!PEACE | HADS‐A | 0.01 | 0.4 | * | * | * |

| Haoa [26] | 2024 | China | 8 | 100 | 100 | 38.26 | 9.07 | CBT | SAS | * | 0.0001 | SDS | * | 0.0001 |

| Hsiu Hsiao [36] | 2025 | Taiwan | 56 | 27 | 29 | 57.24 | 5.94 | MBSR | STAI | * | 0.001 | BDI-II | * | 0.034 |

| AhdiDerav [37] | 2023 | Iran | 8 | 13 | 13 | 33.07 | 4.5 | GCBT | BAI | * | 0.056 | BDI-II | * | 0.856 |

| Zion [38] | 2023 | USA | 12 | 226 | 223 | 52.39 | 11.58 | CBSM | PROMIS | * | 0.019 | PROMIS | * | 0.042 |

| Zhang [39] | 2023 | USA | 8 | 10 | 7 | 20.24 | 2.17 | CBT | GAD-7 | * | 0.05 | HADS‐D | * | 0.05 |

| Guo [40] | 2022 | China | 48 | 69 | 69 | 68.2 | 4.3 | RTICP | HADS- A | * | 0.014 | HADS‐D | * | 0.007 |

| Børøsund [41] | 2022 | USA | 12 | 84 | 88 | 51.7 | 10.5 | CBT | HADS | 0.14 | 0.003 | HADS | 0.19 | 0.002 |

| Murphy [42] | 2021 | USA | 8 | 22 | 22 | 33.6 | 3.68 | MBSR | PROMIS | * | 0.006 | PROMIS | * | 0.172 |

| Ghanbari [43] | 2021 | Iran | 4 | 41 | 41 | 46.9 | 8.8 | CBT | STAI | 1.02 | 0.001 | * | * | * |

| Zhang [44] | 2021 | China | 48 | 80 | 80 | 59.1 | 10.9 | CBT | HADS- A | * | 0.004 | HADS‐D | * | 0.128 |

| Bower [45] | 2021 | USA | 24 | 85 | 81 | 45.5 | 7.7 | MAPs | * | * | * | CES-D | * | 0.016 |

| Victorson [46] | 2020 | USA | 16 | 67 | 59 | 32.8 | 4.76 | MBSR | SAS | * | 0.08 | SDS | * | 0.004 |

| Sutanto [47] | 2021 | Indonesia | 12 | 16 | 16 | 53.5 | 15.39 | CBT | HARS | * | 0.01 | HRSD | * | 0.0072 |

| Fenlon [48] | 2020 | UK | 26 | 63 | 67 | 53.5 | 9.78 | CBT | GAD-7 | * | 0.005 | PHQ | * | 0.006 |

| Grégoire [49] | 2020 | Belgium | 8 | 48 | 47 | 53.85 | 11.91 | CBT | HADS‐A | 0.67 | 0.001 | HADS‐D | 0.71 | 0.001 |

| Teo [50] | 2020 | Singapore | 8 | 27 | 26 | 60.9 | 9.1 | CBT | * | * | * | HADS‐D | * | 0.01 |

| Shao [51] | 2020 | China | 6 | 72 | 72 | 42.3 | 7.5 | MBIs | GAD-7 | 0.21 | 0.446 | PHQ-9 | -0.2 | 0.025 |

*Data not ava ilable

• Study characteristics (author, year, country, design, sample size)

• Participant characteristics (demographics)

• Intervention details (type, format, duration, theoretical basis)

• Outcome measures and results (means, standard deviations, effect sizes).

Data Synthesis

We will perform a narrative synthesis, summarizing the characteristics and findings of all included studies. If studies are sufficiently homogeneous in terms of populations, interventions, comparators, and outcomes, we will conduct a meta-analysis using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software.

Statistical analyses

To evaluate the efficacy of psychosocial interventions on anxiety and depression, the analysis was based on mean changes and standard deviations (SDs) extracted from the included studies. All outcomes for anxiety and depression were analyzed as continuous variables. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. In cases of missing data, studies with critical missing outcome data (e.g., post-intervention scores for anxiety/depression) were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Results

Included Studies

The study selection process is detailed in Figure 1. Our systematic search of databases initially identified 498 records, with an additional 15 records sourced from other references, yielding a total of 513 publications. After the removal of 25 duplicates, 488 unique records were screened based on their titles and abstracts. This led to the exclusion of 413 records that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 75 full-text articles were thoroughly assessed for eligibility. Of these, 36 were excluded for the following reasons: the intervention was not psychosocial (n=28), the study was not related to adult cancer patients (n=4), or the population involved pediatric cancer (n=4). Consequently, 39 studies were deemed eligible and included in the qualitative synthesis of this systematic review.

Baseline characteristics of included studies

The systematic review incorporated 39 randomized controlled trials with considerable diversity in geographical and demographic characteristics. The studies were conducted across 15 countries, with notable representation from the USA, China, and Iran. The total sample size encompassed a wide range, with individual study recruitment varying from 20 to 449 participants. The mean age of participants across the studies was 50.6 years, reflecting a focus on the adult cancer population, though the age range was broad (from 20.2 to 70.6 years). A variety of psychosocial interventions were evaluated, with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and its variants being the most frequently investigated modality, followed by mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) and cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM). The follow-up duration also varied considerably, ranging from 4 to 56 weeks post-intervention. This heterogeneity in sample size, intervention type, and cultural context strengthens the generalizability of the findings across different patient populations and healthcare settings. The baseline characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 2.

Risk of bias of included studies

The methodological quality of the 39 included randomized controlled trials was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool [52]. The majority of studies were judged to have a low risk of bias, demonstrating robust randomization procedures and low attrition rates. Some concerns, primarily due to the inherent inability to blind participants to psychosocial interventions, were noted in several studies; however, this was not deemed to substantially compromise the overall validity of the findings for self-reported outcomes. The evidence base was thus considered of reasonably high quality.

Analyses of outcomes

Based on the results from the 39 studies included in our systematic review, the following findings regarding the efficacy of psychosocial interventions on depression and anxiety in cancer patients can be reported:

Depression

The synthesized evidence indicates that several psychosocial interventions demonstrated statistically significant efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms compared to control conditions. Notably, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and its variants consistently showed significant reductions in depression scores across multiple studies (e.g., Børøsund et al., 2022: MD= -2.3, p=0.002; Phiri et al., 2025: MD= -2.97, p=0.038) [22, 41]. Furthermore, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) also yielded significant benefits, as evidenced by studies such as Can et al. (2024) which reported a substantial reduction in depression (MD= -4.5, p=0.001) [29]. The effect sizes for these interventions varied from small to large, suggesting a robust positive impact on managing depression in cancer patients.

Anxiety

Similarly, the analysis revealed that various psychosocial interventions were effective in alleviating anxiety symptoms. CBT emerged as a prominently effective intervention, with studies like Abbas et al. (2025) and Grégoire et al. (2020) reporting significant decreases in anxiety measures (p=0.001 for both) [17, 53]. Additionally, Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management (CBSM) was found to be particularly effective, as shown in studies such as Hao [26] (p=0.007) and Zion (p=0.019) [38]. While most interventions demonstrated positive effects, their comparative efficacy varied, with CBT and CBSM appearing among the most consistently beneficial approaches for reducing anxiety in this population.

The cumulative findings underscore the overall value of structured psychosocial interventions, particularly those rooted in cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based frameworks, for improving psychological well-being in cancer patients.

Analysis of Intervention Duration and its Effect on Anxiety and Depression

The duration of psychosocial interventions, measured by the follow-up period in weeks, appears to have a complex and non-linear relationship with the outcomes for anxiety and depression in cancer patients. The data does not suggest a simple “longer is always better” conclusion; instead, the effectiveness seems to be influenced by a combination of duration, intervention type, and possibly the intensity of the protocol.

1. Short-Term Interventions (4-8 Weeks)

Interventions in this range demonstrated some of the most potent and statistically significant results.

Examples:

- Chen et al. 4 weeks (CST): Reported highly significant reductions in both anxiety (p=0.021) and depression (p=0.003) [28].

- Can et al. 4 weeks (MBSR): Showed large effect sizes (1.26 for anxiety, 1.03 for depression) with high significance (p=0.001) [28].

- Haoa et al. 8 weeks (CBT): Found dramatic, highly significant reductions in anxiety and depression (p=0.0001) [26].

Interpretation: This suggests that brief, structured, and focused protocols (like certain forms of CBT, MBSR, and CST) can produce rapid and significant psychological benefits. This is crucial for cancer patients who may be undergoing demanding medical treatments and have limited energy for lengthy psychological programs.

2. Medium-Term Interventions (12-16 Weeks)

This was the most common duration and showed consistent, reliable efficacy across various intervention types.

Examples:

- Xia - 12 weeks (CBSM): Significant improvements in anxiety (p=0.003) and depression (p=0.015) [14].

- Zhang - 12 weeks (MBIs): Highly significant results for both outcomes (p=0.001) [15].

- Huang - 12 weeks (PICFHE): Highly significant reductions in anxiety and depression (p=0.001) [27].

Interpretation: The 12-week model appears to be a “sweet spot,” providing sufficient time for skills acquisition, practice, and consolidation. It allows for a more comprehensive exploration of themes than shorter protocols, leading to robust and dependable outcomes.

3. Long-Term Interventions (24+ Weeks)

The results for longer-term interventions were mixed and less conclusive.

Example of Potential Long-Term Benefit:

- Bower et al. - 24 weeks (MAPs): Showed a significant reduction in depression (p=0.016) [45], suggesting some interventions may require or benefit from a longer timeframe to manifest effects on well-being.

Examples of Ambiguous Results:

- Holtmaat - 24 weeks (Meaning-Centered): While a significant effect on depression was found (p=0.005), anxiety data was “not available,” making a full assessment difficult [20].

- Hsiu Hsiao - 56 weeks (MBSR): Reported significant p-values (p=0.001 for anxiety, p=0.034 for depression)

[36] but listed all data as “not available,” which precludes a confident analysis of the magnitude of benefit.

Interpretation: The mixed results in long-term studies could be due to several factors: higher dropout rates over time, the “plateauing” of initial benefits, or the increasing influence of external factors (e.g., disease progression) that overshadow the intervention’s effect.

Overall Conclusion and Hypothesis

Based on this dataset:

1. Rapid Response is Possible: Brief interventions (4-8 weeks) can be highly effective, particularly if they are structured and skill-based (e.g., CBT, MBSR).

2. Optimal Consistency: Medium-duration interventions (12-16 weeks) provide the most consistent evidence of efficacy, balancing depth with practicality.

3. Diminishing Returns? There is no clear evidence that longer interventions (24+ weeks) yield superior outcomes compared to medium-length ones. The benefits may stabilize, and methodological challenges (attrition, missing data) become more prominent.

The type and structure of the intervention (e.g., CBT, Mindfulness) seem to be a stronger determinant of success than duration alone. A well-designed 8-week program can be more effective than a less structured 24-week program. The optimal approach is likely a sufficiently long, intensive, and protocol-driven intervention tailored to the patient’s needs and capacity, with 8-16 weeks being a particularly effective range according to this body of evidence.

Discussion

This systematic review of 39 RCTs provides a comprehensive update on the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for anxiety and depression in cancer patients. The findings consistently demonstrate that psychosocial interventions confer significant benefits, corroborating and extending the existing literature on psycho-oncology. The robust efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) observed in our analysis aligns consistently with earlier meta-analyses. For instance, our finding that CBT produced significant reductions across diverse populations reinforces the conclusions of a previous large-scale review by Faller et al. [10], which established CBT as a well-validated approach. However, our review adds nuance by demonstrating this efficacy persists even in brief (4-8 week) protocols, a finding that contrasts with some earlier recommendations favoring longer durations [20]. Similarly, the significant benefits of Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs) corroborate the work of Zhang et al. [39], yet our duration analysis reveals an important distinction: while their review suggested dose-response relationships, our data indicate that even abbreviated mindfulness protocols can yield substantial effects, particularly for anxiety. This suggests that the core mechanisms of mindfulness present-moment awareness and non-judgmental acceptance may be accessible through condensed, intensive training.

The promising results for Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy warrant special attention. Our findings support the growing evidence base for existential approaches in psycho-oncology, consistent with Breitbart’s pioneering work [54]. The significant effects on depression particularly suggest that addressing existential distress may tap into a different mechanism of change than cognitive-behavioral approaches, potentially offering an alternative for patients who don’t respond to traditional CBT.

Novel Contributions and Clinical Implications

Our analysis makes several unique contributions to the field. First, the geographical diversity of included studies (15 countries) provides stronger evidence for cross-cultural applicability than previous reviews limited primarily to Western populations. The consistent efficacy of CBT and MBIs across these settings suggests these approaches can be successfully adapted while maintaining core therapeutic elements.

Second, our duration analysis offers practical guidance for clinical implementation. The equivalent efficacy of brief (4-8 week) and standard (12-16 week) protocols for many interventions addresses a critical barrier in oncology settings patient burden during active treatment. This finding supports the development of stepped-care models where brief interventions serve as first-line psychological support.

Third, the mixed results for long-term interventions (24+ weeks) highlight an important consideration for future research. While some studies showed sustained benefits, others demonstrated attenuation effects, possibly due to the natural course of psychological adaptation to cancer. This suggests that booster sessions or maintenance programs might be more efficient than continuous long- term intervention.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered. First, there was a considerable degree of heterogeneity in terms of intervention protocols, outcome measures, and patient populations. Second, the inherent difficulty of blinding participants to psychosocial interventions introduces a potential for performance bias. Finally, the long-term follow-up data was sparse, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the sustainability of the observed effects.

In conclusion, this systematic review provides compelling evidence that psychosocial interventions are a vital component of comprehensive cancer care. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Mindfulness-Based Interventions, and Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management stand out as particularly effective, well-validated approaches for alleviating the burdens of anxiety and depression in this vulnerable population.

The evidence indicates that shorter, structured programs (8-12 weeks) are often sufficient to produce significant clinical benefits, offering a practical and scalable model for integration into oncology settings. Future research should move beyond merely establishing efficacy and focus on identifying the most effective intervention components, optimizing delivery formats (e.g., digital health), and personalizing treatment based on patient characteristics, cancer type, and treatment phase to maximize the reach and impact of psychosocial support in oncology.

Ethical Considerations

Not Applicable

Author contribution

All authors have equal contributed to implementation of this research. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available upon request from the authors.

AI Disclosure

Grammarly was used to moderate the linguistic improvement.

References

- Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL , Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2021;71(3). CrossRef

- Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies Mitchell AJ , Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N. The Lancet. Oncology.2011;12(2). CrossRef

- NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Distress Management, Version 2.2023 Riba MB , Donovan KA , Ahmed K, Andersen B, Braun I, Breitbart WS , Brewer BW , et al . Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN.2023;21(5). CrossRef

- Four-week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities Mehnert A, Brähler E, Faller H, Härter M, Keller M, Schulz H, Wegscheider K, et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2014;32(31). CrossRef

- Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence DiMatteo M. R., Lepper H. S., Croghan T. W.. Archives of Internal Medicine.2000;160(14). CrossRef

- Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis Pinquart M., Duberstein P. R.. Psychological Medicine.2010;40(11). CrossRef

- Host factors and cancer progression: biobehavioral signaling pathways and interventions Lutgendorf SK , Sood AK , Antoni MH . Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2010;28(26). CrossRef

- Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation Andersen BL , DeRubeis RJ , Berman BS , Gruman J, Champion VL , Massie MJ , Holland JC , et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2014;32(15). CrossRef

- Psychosocial interventions for anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: achievements and challenges Jacobsen PB , Jim HS . CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2008;58(4). CrossRef

- Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Küffner R. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2013;31(6). CrossRef

- Protocol for the MATCH study (Mindfulness and Tai Chi for cancer health): A preference-based multi-site randomized comparative effectiveness trial (CET) of Mindfulness-Based Cancer Recovery (MBCR) vs. Tai Chi/Qigong (TCQ) for cancer survivors Carlson LE , Zelinski EL , Speca M, Balneaves LG , Jones JM , Santa Mina D, Wayne PM , et al . Contemporary Clinical Trials.2017;59. CrossRef

- Psychotherapy and survival in cancer: the conflict between hope and evidence Coyne JC , Stefanek M, Palmer SC . Psychological Bulletin.2007;133(3). CrossRef

- The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews Page MJ , McKenzie JE , Bossuyt PM , Boutron I, Hoffmann TC , Mulrow CD , Shamseer L, et al . BMJ (Clinical research ed.).2021;372. CrossRef

- The Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management on Loneliness, Spiritual Well-Being, Anxiety, and Depression in Patients with Unresectable Advanced Gastric Carcinoma: A Randomized, Controlled Study Xia S. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine.2025;267(1). CrossRef

- Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Alleviates Depression, Anxiety, and Internalized Stigma Compared With Treatment-as-Usual Among Head and Neck Cancer Patients: Findings From a Randomized Controlled Trial Zhang Z, Zhang Q, Lu P, Shari NI , Nik Jaafar NR , Mohamad Yunus MR , Qiu Q, et al . Depression and Anxiety.2025;2025. CrossRef

- Digital mindfulness-based intervention for people with COPD - a multicentre pilot and feasibility RCT Tschenett H, Vafai-Tabrizi F, Zwick RH , Valipour A, Funk , Nater UM . Respiratory Research.2025;26(1). CrossRef

- A clinical trial of cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric comorbidity and quality of life with Cancer Patients during Chemotherapy (CPdC) Abbas Q, Arooj N, Baig KB , Khan MU , Khalid M, Shahzadi M. BMC psychiatry.2022;22(1). CrossRef

- A Novel CBGT Model for Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Pulmonary Nodules Tao Z, Li S, Nie J, Ni Z, Lei Jiang n, Ma H. BMC psychology.2025;13(1). CrossRef

- A randomized controlled pilot study of yoga skills training versus an attention control delivered during chemotherapy administration Sohl S.J., Tooze J.A., Johnson E.N., Ridner S.H., Rothman R.L., Lima C.R.. J Pain Symptom Manage.2022;63(1). CrossRef

- Efficacy and budget impact of a tailored psychological intervention program targeting cancer patients with adjustment disorder: A randomised controlled trial Holtmaat K., Beek F.E., Wijnhoven L.M.A., Custers J.A.E., Aukema E.J., Eerenstein S.E.J.. Psychooncology.2025;34(3). CrossRef

- An examination of the effectiveness of mindfulness-integrated cognitive behavior therapy on depression, anxiety, stress and sleep quality in iranian women with breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial Moghadam M.S., Parvizifard A., Foroughi A., Ahmadi S.M., Farshchian N.. Sci Rep.2025;15(1). CrossRef

- Effectiveness of group-based multicomponent psychoeducational intervention on anxiety, depressive symptoms, quality of life, and coping among caregivers of children with cancer: A randomised controlled trial Phiri L., Li H.W.C., Phiri P., Choi K.C., Wanda-Kalizang'oma W., Nkhandwe G.. Int J Nurs Stud.2025;171(105205). CrossRef

- Randomized controlled trial of group-blended and individual-unguided online mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to reduce psychological distress in people with cancer Badaghi N., Kwakkenbos L., Prins J., Donders R., Kelders S., Speckens A.. Psychooncology.2025;34(9). CrossRef

- Supporting patients with advanced cancer and their spouses in parenting minor children: Results of a randomized controlled trial Milbury K., Ann-Yi S., Whisenant M.S., Jones M., Li Y., Necroto V.. Oncologist.2025;30(7). CrossRef

- A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation combined with brainlink intelligent biofeedback instrument on pancreatic cancer patients under chemotherapy Mi N., Zhang S.T., Sun X.L., Li T., Liao Y., Dong L.. Brain Behav.2024;14(12). CrossRef

- Personalised graded psychological intervention on negative emotion and quality of life in patients with breast cancer Hao X., Yi Y., Lin X., Li J., Chen C., Shen Y.. Technol Health Care.2024;32(4). CrossRef

- Individual predictors of response to a behavioral activation-based digital smoking cessation intervention: A machine learning approach Huang S., Wahlquist A., Dahne J.. Subst Use Misuse.2024;59(11). CrossRef

- Effectiveness of roy adaptation model-based cognitive stimulation therapy in elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing curative resection Chen C.Y., Ding H., Wang S.S.. Tohoku J Exp Med.2024;263(1). CrossRef

- Effects of a 4-week internet-delivered mindfulness-based cancer recovery program on anxiety, depression, and mindfulness among patients with breast cancer Gu C., Peng Y., Peng Y., Lin S., Yao J., Chen X.. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban.2024;49(7). CrossRef

- Mindfulness to enhance quality of life and support advance care planning: A pilot randomized controlled trial for adults with advanced cancer and their family caregivers Mosher C.E., Beck-Coon K.A., Wu W., Lewson A.B., Stutz P.V., Brown L.F.. BMC Palliat Care.2024;23(1). CrossRef

- Effects of Immersive Virtual Therapy as a Method Supporting the Psychological and Physical Well-Being of Women with a Breast Cancer Diagnosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial Czech O, Kowaluk A, Ściepuro T, Siewierska K, Skórniak J, Matkowski R, Malicka I. Current Oncology.2024;31(10). CrossRef

- Evaluating Group CBT for Depression in Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer Patients in a Malaysian Public Hospital Abd Wahid NH , Ibrahim N, Jamil Osman Z, Emran NA , Horne D, Ismail SIF . Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.2025;26(6). CrossRef

- Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy Versus Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial☆ Marco JH , Llombart P, Romero R, García-Conde A, Corral V, Guillen V, Perez S. Behavior Therapy.2024;55(5). CrossRef

- Mindfulness Meditation Reduces Stress and Hospital Stay in Gastrointestinal Tumor Patients During Perioperative Period Wang X, Lu Y, Gu C, Shao J, Yan Y, Zhang J. Medical Science Monitor.2024;30. CrossRef

- Oncofertility‐related psycho‐educational therapy for young adult patients with breast cancer and their partners: Randomized controlled trial Koizumi T, Sugishita Y, Suzuki‐Takahashi Y, Nara K, Miyagawa T, Nakajima M, Sugimoto K, et al . Cancer.2023;129(16). CrossRef

- The Mindful Compassion Program Integrated with Body-Mind-Spirit Empowerment for Reducing Depression in Lung Cancer Patient-Caregiver Dyads Hsiao F, Ho C, Yu C, Shih J, Lin Z, Huang F, Chen Y, Hsieh C. Psychosocial Intervention.2025;34(1). CrossRef

- Effectiveness of Group Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Managing Anxiety and Depression in Women Following Hysterectomy for Uterine Cancer Ahdi Derav B, Narimani M, Abolghasemi A, Eskandari Delfan S, Akbari R, Ghaemi M, Deldar Pesikhani M. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.2023;24(12). CrossRef

- Effects of a Cognitive Behavioral Digital Therapeutic on Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Patients With Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial Zion SR , Taub CJ , Heathcote LC , Ramiller A, Tinianov S, McKinley M, Eich G, et al . JCO Oncology Practice.2023;19(12). CrossRef

- Evaluating an engaging and coach-assisted online cognitive behavioral therapy for depression among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: A pilot feasibility trial Zhang A, Weaver A, Walling E, Zebrack B, Jackson Levin N, Stuchell B, Himle J. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology.2023;41(1). CrossRef

- Reminiscence therapy involved care programs as an option to improve psychological disorders and patient satisfaction in elderly lung cancer patients: A randomized, controlled study Guo Q, Li T, Cao T, Ma C. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics.2022;18(7). CrossRef

- Digital stress management in cancer: Testing StressProffen in a 12‐month randomized controlled trial Børøsund E, Ehlers SL , Clark MM , Andrykowski MA , Cvancarova Småstuen M, Solberg Nes L. Cancer.2022;128(7). CrossRef

- Consider the Source: Examining Attrition Rates, Response Rates, and Preliminary Effects of eHealth Mindfulness Messages and Delivery Framing in a Randomized Trial with Young Adult Cancer Survivors Murphy KM , Burns J, Victorson D. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology.2021;10(3). CrossRef

- Effects of Psychoeducational Interventions Using Mobile Apps and Mobile-Based Online Group Discussions on Anxiety and Self-Esteem in Women With Breast Cancer: Randomized Controlled Trial Ghanbari E, Yektatalab S, Mehrabi M. JMIR mHealth and uHealth.2021;9(5). CrossRef

- Reminiscence therapy exhibits alleviation of anxiety and improvement of life quality in postoperative gastric cancer patients: A randomized, controlled study Zhang L, Li Y, Kou W, Xia Y, Yu X, Du X. Medicine.2021;100(35). CrossRef

- Targeting Depressive Symptoms in Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: The Pathways to Wellness Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness Meditation and Survivorship Education Bower JE , Partridge AH , Wolff AC , Thorner ED , Irwin MR , Joffe H, Petersen L, Crespi CM , Ganz PA . Journal of Clinical Oncology.2021;39(31). CrossRef

- A randomized pilot study of mindfulness‐based stress reduction in a young adult cancer sample: Feasibility, acceptability, and changes in patient reported outcomes Victorson D, Murphy K, Benedict C, Horowitz B, Maletich C, Cordero E, Salsman JM , Smith K, Sanford S. Psycho-Oncology.2020;29(5). CrossRef

- Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Improving Anxiety, Depression, and Quality of Life in Pre-Diagnosed Lung Cancer Patients Sutanto Y, Ibrahim D, Septiawan D, Sudiyanto A, Kurniawan H. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.2021;22(11). CrossRef

- Effectiveness of nurse‐led group CBT for hot flushes and night sweats in women with breast cancer: Results of the MENOS4 randomised controlled trial Fenlon D, Maishman T, Day L, Nuttall J, May C, Ellis M, Raftery J, et al . Psycho-Oncology.2020;29(10). CrossRef

- Effects of an intervention combining self‐care and self‐hypnosis on fatigue and associated symptoms in post‐treatment cancer patients: A randomized‐controlled trial Grégoire C, Faymonville M, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Charland‐Verville V, Jerusalem G, Willems S, Bragard I. Psycho-Oncology.2020;29(7). CrossRef

- The Feasibility and Acceptability of a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Based Intervention for Patients With Advanced Colorectal Cancer Teo I, Tan Y, Finkelstein EA , Yang GM , Pan FT , Lew HYF , Tan EKW , Ong SYK , Cheung YB . Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.2020;60(6). CrossRef

- The efficacy and mechanisms of a guided self‐help intervention based on mindfulness in patients with breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial Shao D, Zhang H, Cui N, Sun J, Li J, Cao F. Cancer.2021;127(9). CrossRef

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons Higgins JPT TJ , Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T , Page MJ , Welch VA (editors) . 2019.

- Randomized controlled trial of a group intervention combining self-hypnosis and self-care: secondary results on self-esteem, emotional distress and regulation, and mindfulness in post-treatment cancer patients Grégoire C., Faymonville M.-E., Vanhaudenhuyse A., Jerusalem G., Willems S., Bragard I.. Quality of Life Research.2021;30(2). CrossRef

- Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy: An Effective Intervention for Improving Psychological Well-Being in Patients With Advanced Cancer Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Applebaum A, Kulikowski J, Lichtenthal WG . Journal of Clinical Oncology.2015;33(7). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Nursing , 2025

Author Details

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times