First Line Platinum Based Chemotherapy in Malignant Testicular Germ Cell Tumours – A Single Institutional Observational Study

Download

Abstract

Background: Testicular germ cell tumours (TGCTs) are the most common solid malignancy in young men, with excellent prognosis due to the efficacy of platinum-based chemotherapy. However, prospective data from low- and middle-income countries like India are limited.

Materials and methods: This prospective observational study was conducted over two years at a tertiary care hospital in western India. Eligible patients with newly diagnosed malignant testicular GCTs received platinum-based chemotherapy per NCCN 2024 guidelines. Baseline and treatment-related parameters were documented. Treatment response was assessed via RECIST 1.1, and toxicities were graded using CTCAE v5.0. Progression-free survival (PFS) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results: Among 51 registered patients, 34 were eligible. Median age was 34.5 years. Seminoma and non-seminomatous GCT (NSGCT) were equally represented. Most patients (59%) presented with Stage III disease. All patients underwent radical orchiectomy followed by chemotherapy. BEP was the most common regimen. Grade 3 toxicity was rare; pulmonary toxicity occurred in three patients. Overall radiological response rate was 94% (CR 53%, PR 41%), with higher CR in seminoma (76%) than NSGCT (35%). Median follow-up was 11.25 months, with a PFS rate of 91.2%. PFS was 100%, 85%, and 85% in good, intermediate, and poor risk groups, respectively.

Conclusions: Platinum-based chemotherapy remains highly effective and well tolerated in TGCTs, even in resource-constrained settings. Despite delays in diagnosis and treatment, outcomes in this Indian cohort were comparable to global standards, supporting continued adherence to established treatment protocols.

Introduction

Testicular germ cell tumours (TGCTs) are the most common solid malignancy in men aged 15-35 years [1]. The two most common variables that enhance the incidence of testicular cancer by 2-4 times are undescended testis and cryptorchidism [2]. Other risk factors include a family history of TGCT, infertility, testicular dysgenesis syndrome, and certain genetic factors [3]. The advent of Cisplatin based chemotherapy revolutionised the treatment of malignant GCTs resulting in improved outcomes. Even in cases of advanced disease, the prognosis for TGCTs is excellent. When retroperitoneal lymph nodes are involved, the 5-year survival rate can exceed 90% and the cure rate can reach 99% in cases of early-stage disease [4]. Depending on the location and severity of the cancer, the 10-year survival rate in advanced metastatic disease might range from 66 to 94 percent [5].

This study aims to assess the clinical outcomes of Platinum based chemotherapy regimens as first line in treatment of malignant testicular germ cell tumours in a tertiary care hospital in western India in terms of safety and efficacy.

Materials and Methods

A prospective observational study was initiated in July 2022 with collection and analysis of data on patients of malignant testicular germ cell tumours for a period of two years. This cohort of patients after diagnostic and staging workup was treated with platinum-based chemotherapy as per existing guidelines and standard protocols. A structured proforma was designed and used to comprehensively capture data including demographics, baseline characteristics of the disease including clinical, histopathological, radiological and biochemical parameters, stage and risk group (when applicable), details of surgery and chemotherapy and treatment outcomes in terms of response and toxicity parameters. Eligible patients, based on pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) underwent baseline clinical and laboratory assessment for chemotherapy fitness including complete blood counts, liver and renal function tests, 2D Echocardiogram for evaluating cardiac function, pulmonary function test as well as radiological imaging and measurement of serum tumour markers prior to chemotherapy.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| ·Age above 18 years | · Pediatric patients |

| · Newly diagnosed pathologically proven malignant Germ Cell Tumours | · Patients previously treated at any other institution |

| · Testicular primary tumours | · Patients who refuse chemotherapy |

| · Baseline serum tumour markers present (Beta-HCG, AFP, LDH) | · Patients unfit for chemotherapy |

| · Stage I, II and III | · Patients with prior history of other malignancy |

| · ECOG Performance Status ≤ 2 (fit for full dose chemotherapy) | |

| · Eligible for platinum-based chemotherapy | |

| · Baseline blood counts, serum biochemistry & 2D Echocardiogram – Within normal limits | |

| · Normal pulmonary function test for patients receiving Bleomycin |

Patients were treated with platinum-based chemotherapy as per NCCN 2024 guidelines [6]. Serum tumour markers were evaluated prior to each cycle of chemotherapy and at treatment completion.

Radiological reassessment was done at treatment completion and response was defined according to RECIST (Response evaluation criteria in solid tumours) [7] criteria version 1.1. Adverse events were documented using CTCAE (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events) version 5.0 [8]. Data analysis included calculation of response rates and progression free survival (PFS). PFS was calculated as the time from initiation of treatment to disease progression or death. Safety data was calculated in terms of incidence of toxicities, grades of each toxicity and their effect on treatment in terms of necessitating dose reductions, treatment interruptions and/ or treatment discontinuation.

Data was collected and tabulated on Microsoft Excel and analysed using IBM SPSS version 26.0. Quantitative variables were analysed using appropriate statistical methods. Survival analysis was done using the Kaplan-Meier method. For all analysis, p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

51 patients of malignant germ cell tumours were registered at our institution during the defined study period. Three of these patients had mediastinal GCTs and were excluded. Five patients had received some form of chemotherapy prior to attending our institution and were excluded. Nine patients did not review after initial registration and did not receive a single cycle of chemotherapy and were also excluded. Therefore, a total of 34 patients were eligible for the study according to the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

(I) Baseline Characteristics (Table 2)

The median age of the study population was 34.5 years (range – 20 to 53 years).

| Seminoma | NSGCT | Total | ||

| N | 17 | 17 | ||

| Median Age | 37 | 32 | 34.5 | |

| Laterality | Left | 8 | 10 | 18 |

| Right | 9 | 7 | 16 | |

| T stage | 1 | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| 2 | 12 | 4 | 16 | |

| 3 | 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| N stage | 0 | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| 3 | 5 | 9 | 14 | |

| M stage | 0 | 16 | 9 | 25 |

| 1 | 1 | 8 | 9 | |

| S stage | 0 | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| 2 | 9 | 6 | 15 | |

| 3 | 2 | 7 | 9 | |

| AJCC Stage Groups | I | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| II | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| III | 7 | 13 | 20 | |

| IGCCCG Risk Groups | Good | 17 | 3 | 20 |

| Intermediate | 0 | 7 | 7 | |

| Poor | N/A | 7 | 7 |

The median age of patients presenting with Seminomas was 37 years (range – 20 to 50 years) while that for patients with NSGCT was 32 years (range – 19 to 53 years). 31 of the patients had ECOG PS 0-1 at the time of initiation of the study. 3 patients had ECOG PS 2. Patients with ECOG PS 3-4 were not included in the study as they were not fit for optimum intensity and frequency of platinum-based chemotherapy.

The most common initial presenting symptom was painless testicular swelling, accounting for 73.5% cases. 20.6% patients had painful testicular swelling while only 5.9% presented with abdominal or back pain. The median time from onset of first symptom to diagnosis was 3 months (range – 1 to 6 months).

Semen analysis and fertility counselling, including the option of sperm preservation, were offered to all patients. Semen analysis was done in 22 patients. 17 patients underwent sperm preservation. All five unmarried patients underwent sperm preservation. Among the married patients, twelve declined semen analysis and sperm preservation as they had completed their families.

18 of the patients had left-sided testicular tumours while 16 had right testicular involvement. None of the patients had bilateral tumours at the time of presentation. There was equal distribution of seminoma and NSGCT in the study population.

Among patients with NSGCT, mixed NSGCT was most common (59%) followed by Yolk Sac tumours (23%). Among mixed NSGCTs, embryonal component was predominant in 40%.

All patients underwent primary radical high inguinal orchiectomy (HIO). Twelve patients had pT1, sixteen patients had pT2 and six patients had pT3 tumours on histopathological examination of the HIO specimen.

Nodal staging was based on radiological evaluation with CECT scan. Ten patients were cN0, three patients were cN1, seven patients were cN2 and fourteen patients had advanced nodal disease (cN3). In terms of histological type, incidence of node positive disease was 58.8% for seminomas compared to 82.3% for NSGCT.

Nine patients had metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. The incidence of metastatic disease was 5.8% in seminomas and 47% in NSGCT

Seven patients had S0 markers, three patients had S1 markers, thirteen patients had S2 markers, and eight patients had S3 markers. Elevation of tumour markers was more common in NSGCT compared to seminoma. 35% of seminoma patients had S0 markers compared to 6% for NSGCT. Conversely S3 markers were seen in 41% of NSGCT compared to 12% of seminomas.

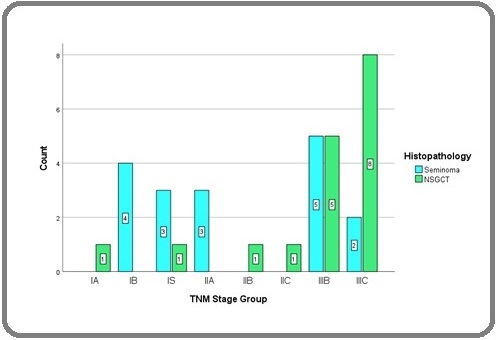

Nine patients had Stage I disease, five patients had Stage II disease, and twenty patients had Stage III disease. Among Seminomas, Stage III was seen in 41% patients while 76% of patients with NSGCT had Stage III disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bar Diagram Showing Distribution of Different Histologies According to AJCC TNM Stage Groups.

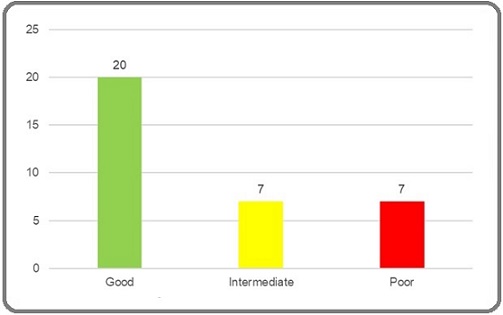

Twenty patients had good risk disease, while seven patients had intermediate and poor risk disease each (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Bar Diagram Showing Distribution of Cases According to IGCCCG Risk Groups.

All patients of seminoma had good risk disease. Among patients with NSGCT, 18% had good risk disease while intermediate and poor risk disease constituted 41% of the cases each.

All patients received platinum-based chemotherapy based on current NCCN [6] recommendations according to TNM stage group and IGCCCG risk group. Pre-treatment evaluation consisted of liver, renal and pulmonary function (including DLCO) tests and evaluation of cardiac function by 2D Echocardiography. All regimens were highly emetogenic and appropriate anti-emetics were prescribed. Peg-GCSF was given to all patients receiving two drug and three drug regimens. Two patients were considered ineligible for Bleomycin based on abnormal pulmonary function and received EP.

(II) Safety

Safety profile depends on the type of regimen used (single agent v/s two drug regimen v/s three drug regimen) and the number of cycles. Data was collected and analysed based on the number of cycles of chemotherapy and the number of toxicity events (Table 3).

| No. of Cycles | Nature of Toxicity | No. of Events | |

| 102 | Haematological | Anaemia | 67 (65.7%) |

| Neutropenia | 11 (11%) | ||

| Thrombo-Cytopenia | NIL | ||

| Non-Haematological | Alopecia | ALL | |

| CINV | 101 (99%) | ||

| Pulmonary Toxicity | 3 (2.9%) | ||

| Cardio-Vascular Toxicity | NIL | ||

| Nephrotoxicity | NIL | ||

| Neurological Toxicity | NIL | ||

| Ototoxicity | NIL | ||

| Skin Changes | 2 (1.9%) |

The salient findings are as follows:

a) Alopecia was seen in all patients.

b) The most common toxicity was CINV occurring in 99% of the chemotherapy cycles.

c) Among haematological toxicities, anaemia was the most common. Neutropenia was seen in 11% of the cases.

d) Pulmonary toxicity was seen in three patients attributable to the use of Bleomycin.

e) There was no incidence of acute cardiac or renal events and no patients reported ototoxicity or neurological symptoms.

Assessment of long-term toxicities was beyond the scope of this study When analysed according to the type of chemotherapy used, the findings were as follows:

(A) BEP Regimen

(i) Grade 1 CINV was seen in 75% cycles. Appropriate antiemetics were used. There was a single event of grade 3 CINV requiring further escalation of antiemetics.

(ii) Anaemia was the most common haematological event.

(iii) There were four events of neutropenia (in spite of primary prophylaxis with Peg-GCSF) and three events of pulmonary toxicity.

(A) EP Regimen

(i) CINV was seen in each cycle and was managed with appropriate anti-emetics

(ii) There was no incidence of neutropenia. (All patients received primary prophylaxis with Injection Peg-GCSF, 24-72 hours after completion of chemotherapy.)

(B) AUC=7 Carboplatin

All patients developed neutropenia. However, none of the patients developed febrile neutropenia. Primary prophylaxis was not used in these cases.

(III) Eficacy

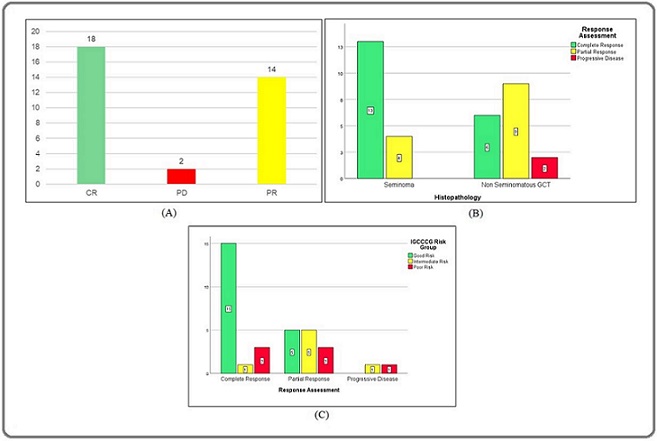

On post-chemotherapy re-evaluation with CECT of thorax, abdomen and pelvis, eighteen patients had complete response (53%), fourteen had partial response (41%) and two patients had progressive disease (6%) according to RECIST criteria version 1.1 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. A, Bar Diagram Showing Radiological Response (N) According oo Recist 1.1. 3B, Bar Diagram Showing Radiological Response (N) According to Histological Type. 3C, Bar Diagram Showing Radiological Response (N) According to IGCCCG Risk Groups.

The overall response rate (ORR, complete and partial radiological responses) was 94%. Complete radiological response was seen in 76% of seminoma compared to 35% of NSGCT (Figure 3B). The respective ORR were 100% and 88.2%. On comparison of radiological ORR by stage, the rates were 100%, 85% and 85% respectively for good, intermediate and poor risk patients (Figure 3C).

On comparison of radiological complete response rates after chemotherapy and pathological complete response rates in patients undergoing evaluation of residual retroperitoneal disease, it is evident that rates of CR are underestimated while considering radiological response alone (Table 4).

| Seminoma (N=17) | NSGCT (N=17) | ||

| Radiological CR | Pathological CR | Radiological CR | Pathological CR |

| 13 (76.4%) | 16 (94.1%) | 6 (35.2%) | 12 (70.5%) |

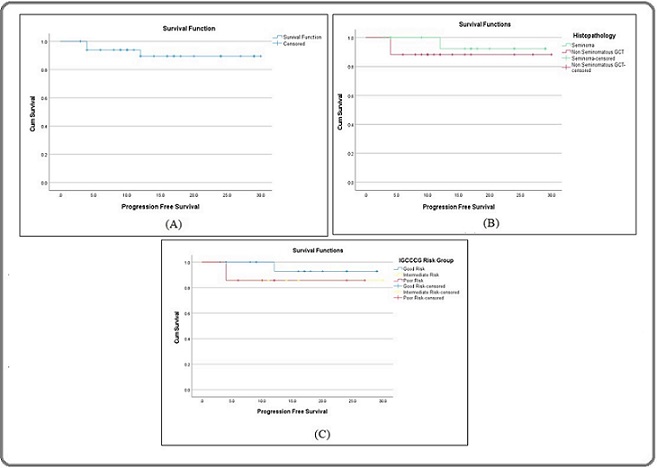

After a median follow-up of 11.25 months (range 1-29 months), the progression free survival rate in the overall study population was 91.2% (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. A, Kaplan Meier Plot Showing Progression Free Survival for the Study Population. B, Kaplan Meier Plot Showing Progression Free Survival According to Histopathology. C, Kaplan Meier Plot Showing Progression Free Survival According to IGCCCG Risk Groups.

For seminomas, the corresponding PFS rate was 94.1% while for NSGCT, the corresponding PFS rate was 88.2% (Figure 4B).

When compared according to AJCC TNM stage groups, progression free survival rate was 100% for stage I and II tumours while it was 85% for stage III. For IGCCCG risk groups, the progression free survival rates for good intermediate and poor risk groups were 95%, 85.7% and 85.7% respectively (Figure 4C).

Discussion

Malignant GCT although common in adolescents and young adults is a rare cancer and is not among the top ten cancers seen in India [9]. Treatment of GCT was revolutionized by the discovery of the sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy and the high cure rate in malignant GCT is considered as one of the successful achievements in the field of oncology [10]. Enough data are available from the developed countries on the demographic features, management, and outcome of testicular GCT. However, the same is not true for low- and middle-income countries like India [11-14]. Delayed presentation, advanced stage, treatment abandonment, and inappropriate treatments are challenges which physicians face in India when managing malignant GCT and therefore extrapolating data from the Western countries may not be informative.

In a study by Singh et. al. [15], at a tertiary care centre in India, the median age of presentation was 31 years with most cases clustered in the age group of 31 to 40 years. There was an equal incidence of Seminoma and NSGCT [15]. Similarly in a study by S.V. Saju et al [16], the median age of presentation was 32 years, with NSGCT accounting for 70% of the cases. All these studies assert that malignant GCT is a disorder of adulthood.

In our study, the median age of presentation was 34.5 years and majority of patients belonged to the age group of 31-40 years. Our study had an equal incidence of seminoma and NSGCT. Joshi et al. [13] observed a median age of 36 and 28 years respectively for Seminoma and NSGCT while the same in our study was 37 and 32 years respectively. Seminoma tends to occur at an older age compared to NSGCT.

Biswas et. al. [17] reported on the incidence of various types of NSGCT and the predominance of individual components in mixed NSCGT specimens. In their study embryonal tumours comprised the most common pure NSGCT as well as the predominant component of mixed NSGCTs while in our study yolk sac tumours predominated in both categories.

Singh et. al.[15] observed that 50% of patients had Stage III tumours. The epidemiological study by Joshi et. al. [13] found that 64% NSGCT and 22.2% of Seminomas had Stage III disease. Our study, however, reported higher numbers of metastatic disease, with 82% NSGCT and 41% Seminomas having Stage III disease at presentation. The relatively higher proportion of advanced-stage disease may be attributable to a lack of awareness and access to tertiary healthcare facilities in rural areas. Such delays in diagnosis and initiation of treatment pose a significant public healthcare gap for a highly curable malignancy.

The same study [15] reported that the majority of NSGCT presented with S0 (30.5%) and S1 (55.5%), whereas the majority of seminomas had S2 markers (46%). In our study 41% of NSGCT had advanced disease with S3 markers, while 46.6% seminomas had S2 markers. The level of serum tumour markers does not influence the risk group in seminoma.

In our study majority of patients presented with good risk disease similar to the data reported by Singh et. al. but contrary to the findings of Joshi et. al. [13] which reported higher proportion of intermediate (47.5%) and poor (30%) risk patients according to IGCCCG risk stratification.

The relatively high proportion of good risk patients can be attributed to the facts that there was an equal number of cases of seminoma and NSGCT and by exclusion of non-testicular primaries, intermediate risk seminoma cases were excluded from the study.

Chemotherapy regimens were selected according to current NCCN [6] guidelines appropriate for stage and risk and were generally well tolerated with minimal incidence of grade 3 or higher toxicity.

In various trials of Bleomycin containing regimens in malignant GCT, rates of any grade of pulmonary toxicity ranged from 5 to 16 percent, and rates of fatal pulmonary toxicity have been in the range of 0-1% for three cycles and 0-3% for four cycles [18-24]. Bleomycin induced pulmonary toxicity appears to be dose dependent and avoidance of a 4th cycle has shown a trend of decreased incidence [25]. Notably in this study, Bleomycin induced pulmonary changes were seen only in a single patient and was incidentally detected (CTCAE grade 1) during management of febrile neutropenia.

Baseline evaluation of pulmonary function test and patient selection for Bleomycin eligibility [26] is important for avoiding Bleomycin induced lung toxicity. In our study, 4 patients were considered ineligible for Bleomycin based on pulmonary function test.

However, because of the short duration of follow-up, assessment of long-term toxicities was beyond the scope of our study.

The incidence of febrile neutropenia ranged from 8%

[27] to 22% [13] in contemporary Indian studies. In our study, only one patient developed febrile neutropenia. Routine primary prophylaxis with Peg-GCSF was given in all patients receiving two drug and three drug combinations as Peg-GCSF reduces the depth and duration of neutropenia.

Platinum based two-drug and three drug regimens in malignant GCT are highly effective, producing high overall and complete response (77% in intermediate to poor risk patients as reported by William SD et. al. [28]) rates. In selected contemporary Indian studies [11-17], the overall response rate (ORR) ranged from 78% to 92%.

In our study, the ORR was 94%. Nair et. al. [29] reported CR rate of 59% while our study showed a CR rate of 52%.

For stage I seminoma, single agent Carboplatin is one of the recommended treatment modalities. In a phase III trial conducted by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), at a median follow-up of 6.5 years, relapse-free rate with carboplatin was 94.7% [30]. In our study, none of the patients treated with single agent Carboplatin were found to have disease relapse during the study at a median follow up of 11.25 months. In stage I NSGCT, SWENOTECA reported that patients with LVI who received a single cycle of BEP, the relapse rate was 3.2 percent and five-year disease-specific survival was 100 percent [31]. In our study, only one patient with stage I NSGCT received a single cycle of BEP and remained disease free at the time of reporting. GETUG T93BP assigned good risk advanced testicular

GCTS to BEP for three cycles or EP for four cycles (using standard doses) [32]. The overall response rate was equivalent between EP and BEP (97 versus 96 percent, respectively). In intermediate to poor risk advanced GCTs, treatment with four cycles BEP resulted in a complete response rate of 77% and 2-year OS rate of 80 percent [28]. In our study, the ORR was 100%, 85% and 85% respectively for good, intermediate and poor risk patients. However, for intermediated to poor risk patients, the radiological CR rate was only 28.5%. If pathological response in RPLND specimens were considered in those patients undergoing RPLND for residual disease, the CR rate was 64.3% in intermediate and poor risk patients.

Singh et. al. [27] stratified outcomes based on histology for stage III GCTs, 75% patients of stage III seminoma and 60% of stage III NSGCT were alive and disease free in the mean follow-up periods of 5 years and 4 years respectively in the study. In our study, progression free survival rate was 85% for stage III GCTs while the PFS rates were 94.1% and 88.2% for seminoma and NSGCT respectively for all stages.

A residual mass is detected in approximately 30% patients of NSGCT after chemotherapy [33]. Of these, 50% are necrotic, 40% show teratoma and 10% show viable NSGCT [33]. In a series of 598 patients, it was seen that 5-year DFS rate was 94% in patients having no viable residual tumour on post-chemotherapy RPLND [34].

In the study by Biswas et. al. [17], 29% patients with advanced NSGCT underwent RPLND and viable tumour was detected in 46% of those patients. In our study 54% of patients with advanced NSGCT with residual disease underwent RPLND indicating a greater degree of adherence to treatment guidelines and protocols. None of the patients showed residual viable tumour. The major hurdle in this regard appears to be the unwillingness to undergo a second surgical procedure.

In case of seminomas, among the four patients who had residual disease, only one patient underwent whole body PET CT scan and was found to have no metabolically active residual disease.

There is an apparent disparity between the rates of radiological and pathological CR rates in our study. However, germ cell tumours being highly chemosensitive often leave behind necrotic tissue which may be mistaken for a residual disease leading to unnecessary treatment with further cytotoxic therapy. Hence evaluation of the residual tumour with RPLND in case of NSGCT or PET-CT and biopsy for seminoma is essential for optimal management of the patient.

At a median follow up of 11.25 months, the progression free survival rate in the overall study population was 91.2%. Progression free survival is a surrogate marker for predicting overall survival in multiple solid tumours. Adra et al. [35] investigated the factors affecting prognosis and survival in poor risk germ cell tumours and concluded that PFS does not correlate with OS in such a setting. However, the duration of our study did not permit analysis of overall survival and any conclusion regarding such correlation was beyond the scope of our study.

In conclusion, the management of testicular germ cell tumours has been one of the great success stories in oncology. There are well established guidelines for the management of germ cell tumours. However, there are certain challenges faced in low- and middle-income countries due to delayed referrals and inadequate staging and workup. There is also a paucity of prospective Indian data reporting outcomes of patients with germ cell tumours. Our study aimed to prospectively evaluate treatment outcomes in terms of survival and toxicity in such patients and found that outcomes were comparable to both historical standards as well as available Indian data in spite of such socio-economic and logistic hurdles.

Limitations

There were only 34 eligible patients for this study; a higher number would have allowed for a better evaluation of the factors affecting the outcomes in our study. A higher sample size would have allowed the study’s results to be more representative of the disease burden and real-world treatment outcomes. However, being a single institutional study with a period of enrolment of two years, it was not possible to include more patients for a malignancy with a relatively low incidence in our population.

The duration of our study was two years, which limited the number of patients enrolled as well as the evaluation of long-term outcomes. As a result, overall survival data and long-term treatment-related toxicities could not be assessed.

All patients of NSGCT who had residual disease after primary chemotherapy did not undergo RPLND. The reluctance of patients to undergo a second surgery may compromise long term survival outcomes.

According to the pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, patients with ECOG PS>2 were excluded from the study. However, a significant proportion of patients in low- and middle-income countries may present with poorer PS and compromised organ function and may not be able to tolerate optimal intensity and frequency of chemotherapy which may have implications on long term outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Statement of Transparency and Principals:

• Author declares no conflict of interest

• Study was approved by Research Ethic Committee of author affiliated Institute.

• Study’s data is available upon a reasonable request.

• All authors have contributed to implementation of this research.

References

- Future of testicular germ cell tumor incidence in the United States: Forecast through 2026 Ghazarian AA , Kelly SP , Altekruse SF , Rosenberg PS , McGlynn KA . Cancer.2017;123(12). CrossRef

- Risk factors for prostate and testicular cancer Boyle P., Zaridze D. G.. European Journal of Cancer.1993;29(7). CrossRef

- Our 10 years’ Experience in Testicular Tumors Kalkan S, Çalışkan S. HAYDARPAŞA NUMUNE MEDICAL JOURNAL.2020;60(3). CrossRef

- Cancer Research UK. Cancer Stats. Testicular cancer-UK. London. Cancer Res UK. 2002 .

- Stage II Testicular Seminoma: Patterns of Recurrence and Outcome of Treatment Chung PWM , Gospodarowicz MK , Panzarella T, Jewett MAS , Sturgeon JFG , Tew-George B, Bayley AJS , et al . European Urology.2004;45(6). CrossRef

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines: Testicular Cancer. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/testicular.pdf .

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5. Published: November 27. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute .

- Cancer incidence in India. Globocan 2018. http://www.gco.iarc. fr. Accessed 22 Dec 2018 .

- Brachyury oncogene is a prognostic factor in high-risk testicular germ cell tumors Pinto F., Cárcano F. M., Silva E. C. A., Vidal D. O., Scapulatempo-Neto C., Lopes L. F., Reis R. M.. Andrology.2018;6(4). CrossRef

- Testicular cancer--discoveries and updates Hanna NH , Einhorn LH . The New England Journal of Medicine.2014;371(21). CrossRef

- Clinical profile and problems of management of 108 cases of germ cell tumours of testis at Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, All India Institute of Medical Sciences New Delhi 1985-1990 Raina V., Shukla N. K., Rath G. K., Gupta N. P., Mishra M. C., Chaterjee T. K., Kripalani A. K.. British Journal of Cancer.1993;67(3). CrossRef

- Germ cell tumours in uncorrected cryptorchid testis at Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, New Delhi Raina V., Shukla N. K., Gupta N. P., Deo S., Rath G. K.. British Journal of Cancer.1995;71(2). CrossRef

- Epidemiology of male seminomatous and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors and response to first-line chemotherapy from a tertiary cancer center in India Joshi A., Zanwar S., Shetty N., Patil V., Noronha V., Bakshi G., Prakash G., Menon S., Prabhash K.. Indian Journal of Cancer.2016;53(2). CrossRef

- Germ cell tumours of the testis: clinical features, treatment outcome and prognostic factors Bhutani M, Kumar L, Seth A, Thulkar S., Vijayaraghavan M., Kochupillai V.. The National Medical Journal of India.2002;15(1). CrossRef

- Epidemiology and treatment outcomes of testicular germ cell tumor at tertiary care center in Patna, India: A retrospective analysis Singh, Dharmendra , Singh, Pritanjali , Mandal, Avik . Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care.2025. CrossRef

- Factors that impact the outcomes in testicular germ cell tumors in low-middle-income countries Saju S. V., Radhakrishnan V, Ganesan TS , Dhanushkodi M, Raja A, Selvaluxmy G, Sagar TG . Medical Oncology (Northwood, London, England).2019;36(3). CrossRef

- Outcome of testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumours: Report from a tertiary cancer centre in eastern India Biswas B, B, Dabkara D, Ganguly S, Ghosh J, Gupta S, Sen S, Chatterjee M. Ecancermedicalscience.2025. CrossRef

- Poor prognosis nonseminomatous germ-cell tumours (NSGCTs): should chemotherapy doses be reduced at first cycle to prevent acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with multiple lung metastases? Massard C., Plantade A., Gross-Goupil M., Loriot Y., Besse B., Raynard B., Blot F., et al . Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology.2010;21(8). CrossRef

- Randomized comparison of cisplatin and etoposide and either bleomycin or ifosfamide in treatment of advanced disseminated germ cell tumors: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Southwest Oncology Group, and Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study Nichols C. R., Catalano P. J., Crawford E. D., Vogelzang N. J., Einhorn L. H., Loehrer P. J.. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.1998;16(4). CrossRef

- Randomized Trial Comparing Bleomycin/Etoposide/Cisplatin With Alternating Cisplatin/Cyclophosphamide/Doxorubicin and Vinblastine/Bleomycin Regimens of Chemotherapy for Patients With Intermediate- and Poor-Risk Metastatic Nonseminomatous Germ Cell Tumors: Genito-Urinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Centers Trial T93MP Culine S, Kramar A, Théodore C, Geoffrois L, Chevreau C, Biron P, Nguyen BB , et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology.2008;26(3). CrossRef

- Phase III randomized trial of conventional-dose chemotherapy with or without high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem-cell rescue as first-line treatment for patients with poor-prognosis metastatic germ cell tumors Motzer RJ , Nichols CJ , Margolin KA , Bacik J, Richardson PG , Vogelzang NJ , Bajorin DF , et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2007;25(3). CrossRef

- Importance of bleomycin in combination chemotherapy for good-prognosis testicular nonseminoma: a randomized study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genitourinary Tract Cancer Cooperative Group Wit R., Stoter G., Kaye S. B., Sleijfer D. T., Jones W. G., Bokkel Huinink W. W., Rea L. A., Collette L., Sylvester R.. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.1997;15(5). CrossRef

- Importance of bleomycin in favorable-prognosis disseminated germ cell tumors: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial Loehrer P. J., Johnson D., Elson P., Einhorn L. H., Trump D.. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.1995;13(2). CrossRef

- Equivalence of three or four cycles of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin chemotherapy and of a 3- or 5-day schedule in good-prognosis germ cell cancer: a randomized study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genitourinary Tract Cancer Cooperative Group and the Medical Research Council Wit R., Roberts J. T., Wilkinson P. M., Mulder P. H., Mead G. M., Fosså S. D., Cook P., et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2001;19(6). CrossRef

- Pulmonary Function in Patients With Germ Cell Cancer Treated With Bleomycin, Etoposide, and Cisplatin Lauritsen J, Kier MGG , Bandak M, Mortensen MS , Thomsen FB , Mortensen J, Daugaard G. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2016;34(13). CrossRef

- Cisplatin, etoposide and either bleomycin or ifosfamide in the treatment of disseminated germ cell tumors: final analysis of an intergroup trial Hinton S, Catalano PJ Paul J., Einhorn LH , Nichols CR , David Crawford E., Vogelzang N, Trump D, Loehrer PJ . Cancer.2003;97(8). CrossRef

- Management of testicular tumors- SGPGIMS experience Singh V, Srivastava A, Srivastava A, Kumar A, Kapoor R, Mandhani A. Indian Journal of Urology.2004;20(2). CrossRef

- Treatment of disseminated germ-cell tumors with cisplatin, bleomycin, and either vinblastine or etoposide Williams S. D., Birch R., Einhorn L. H., Irwin L., Greco F. A., Loehrer P. J.. The New England Journal of Medicine.1987;316(23). CrossRef

- Prognostic factors and outcomes of nonseminomatous germ cell tumours of testis-experience from a tertiary cancer centre in India Nair LM , Krishna KMJ , Kumar A, Mathews S, Joseph J, James FV . Ecancermedicalscience.2020;14. CrossRef

- Randomized trial of carboplatin versus radiotherapy for stage I seminoma: mature results on relapse and contralateral testis cancer rates in MRC TE19/EORTC 30982 study (ISRCTN27163214) Oliver RTD , Mead GM , Rustin GJS , Joffe JK , Aass N, Coleman R, Gabe R, Pollock P, Stenning SP . Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2011;29(8). CrossRef

- One course of adjuvant BEP in clinical stage I nonseminoma mature and expanded results from the SWENOTECA group Tandstad T., Ståhl O., Håkansson U., Dahl O., Haugnes H. S., Klepp O. H., Langberg C. W., et al .. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology.2014;25(11). CrossRef

- Refining the optimal chemotherapy regimen for good-risk metastatic nonseminomatous germ-cell tumors: a randomized trial of the Genito-Urinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Centers (GETUG T93BP) Culine S., Kerbrat P., Kramar A., Théodore C., Chevreau C., Geoffrois L., Bui N. B., et al . Annals of Oncology.2007;18(5). CrossRef

- Testicular cancer in 2023: Current status and recent progress McHugh DJ , Gleeson JP , Feldman DR . CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2024;74(2). CrossRef

- Clinical Outcome of Patients with Fibrosis/Necrosis at Post-Chemotherapy Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection for Advanced Germ Cell Tumors Mano R, Becerra MF , Carver BS , Bosl GJ , Motzer RJ , Bajorin DF , Feldman DR , Sheinfeld J. The Journal of Urology.2017;197(2). CrossRef

- Prognostic factors in patients with poor-risk germ-cell tumors: a retrospective analysis of the Indiana University experience from 1990 to 2014 Adra N., Althouse S. K., Liu H., Brames M. J., Hanna N. H., Einhorn L. H., Albany C.. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology.2016;27(5). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology , 2025

Author Details