Cytopathological Spectrum of Salivary Gland Lesions According to the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: A Retrospective Study

Download

Abstract

Background and objective: The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC), developed in 2015, aims to standardize reporting of salivary gland cytology, enhance communication between clinicians and institutions, and ultimately improve patient care outcomes. This study aimed to determine the cytopathological spectrum of salivary gland lesions using the MSRSGC at a tertiary care hospital in northeast India.

Materials and Methods: Clinical data and cytology smears of salivary gland lesions diagnosed between January 2016 and May 2021 were retrieved. All cytology smears were reviewed and reclassified into one of the six MSRSGC categories using strict criteria. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) for detecting malignant lesions were calculated using histopathological examination (HPE) as the gold standard.

Results: A total of 57 salivary gland lesions were examined. Thirty-one (54.38%) were male and 26 (45.6%) were female, with a median age of 34 years (range 6-70 years). Statistical analysis revealed a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 100%, positive predictive value of 100%, negative predictive value of 95%, and a diagnostic accuracy of 95.65%. MSRSGC Category IVa was the most common, with 29 cases of pleomorphic adenoma.

Conclusion: The overall diagnostic accuracy of cytological reporting of salivary gland lesions based on the Milan nomenclature in our institution was 95.65%. Our findings demonstrate the positive contribution of the MSRSGC towards accurately identifying malignant lesions, thereby assisting clinicians in making informed management decisions.

Introduction

Salivary gland neoplasms account for less than 3% of all head and neck tumours. Salivary glands are exocrine glands that include major and minor salivary glands. A nodule or diffuse enlargement of the salivary glands may be caused by infections, inflammation, cystic lesion, degenerative process, obstructions, or benign/malignant neoplasm [1].

The role of fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the initial evaluation of salivary gland lesions is well established [2-4]. However, the diversity and heterogenicity of these lesions, the cytomorphological overlap between different types and inherent FNAC pitfalls often pose challenges for the cytopathologist to diagnose salivary gland lesions by FNAC accurately [5, 6]. Also, adding new entities by the updated 2017 WHO classification of head and neck tumours makes accurate subtyping of salivary gland lesions by FNAC more challenging [7]. So a descriptive cytological report without a definite diagnosis often made it difficult for the treating clinician to interpret the information and devise a specific management plan. Since there was no standard cytologic evidence-based reporting system for salivary gland lesions, a need for a tiered classification system of salivary gland FNAC was felt to ensure uniformity in reporting and provide relevant information to clinicians [8, 9].

To address the need for a diagnostic framework, the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC) was developed in 2015 by an international task force of cytopathologists, surgical pathologists, and head and neck surgeons through the American Society of Cytopathology and International Academy of Cytology [10]. The objective of the MSRSGC is to standardize reporting of salivary gland cytology, promote better communication between clinicians and institutions, and ultimately improve patient care. This comprised of six categories, including non-diagnostic (category I), non-neoplastic (category II), atypia of undetermined significance (category III), benign neoplasm (category IVa), salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (SUMP) (category IVb), suspicious for malignancy (category V), and malignant (category VI). This classification system also mentions the estimated risk of malignancy (ROM) and clinical management recommendations for each class [11].

Though many studies have already been conducted on this topic, very few studies have been done in northeast India. So, we aim to conduct a retrospective study to determine the cytopathological spectrum of salivary gland lesions using the Milan System for reporting in a tertiary care hospital of northeast India.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in the pathology department, FAAMCH, Assam, from January 2016 to May 2021. Ethical clearance from the institutional ethics committee was obtained. Clinical data of cases and cytology smears of salivary gland lesions during the study period were retrieved. The cytology smears of the salivary gland lesions included FNACs of lesions involving both the major and minor salivary glands. All the cytology smears were reviewed again and reclassified to one of the six categories after applying strict criteria given by MSRSGC. The histological reports and clinical follow up, wherever available, were compared. The risk of malignancy (ROM) was calculated for each category. ROM was determined by dividing the number of malignant cases on histopathology in each category by the total number of patients on cytology in the particular category. For statistical calculations, cytological diagnoses were classified as positive (malignancy) and negative (benign). Patients with negative cytological diagnosis but later diagnosed as malignant on histopathological examination were considered as false negative, whereas patients with positive cytological diagnosis but later diagnosed benign were taken as false positive. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and diagnostic accuracy of FNAC to detect malignant lesions were calculated considering HPE as the gold standard.

Results

A total of 57 salivary gland lesions were examined in the cytology section during the study period. 31 (54.38%) were males, and 26 (45.6%) were females with a male to female ratio of 1.19:1. Our study population’s mean and median age was 35± 16 years and 34 years (range 6-70 years). The most frequent site of involvement was the parotid gland (70.2%), followed by the submandibular gland (26.3%). The minor salivary gland was affected only in 3.5% of cases. All the cases were reviewed and categorized according to the MSRSGC into six categories (Table 1).

| Category | Number (N=57) | Percentage (%) | |

| I | Non-Diagnostic | 5 | 8.70 |

| II | Non-Neoplastic | 14 | 24.60 |

| III | Atypia of undetermined significance | 4 | 7.00 |

| IVa | Neoplasm Benign | 29 | 50.90 |

| Ivb | SUMP | 2 | 3.50 |

| V | Suspicious of malignancy | 1 | 1.80 |

| VI | Malignant | 2 | 3.50 |

The majority of cases belonged to neoplasm benign (50.9%), followed by non-neoplastic (24.6%), non-diagnostic (8.7%), atypia of undetermined significance (7%), SUMP (3.5%), malignant (3.5%) and suspicious of malignancy (1.8%).

The distribution of the cases as per the MSRSGC category are depicted in Table 2 and cytohistopathological correlation with categories of MILAN system are shown in Table 3.

| Milan Category | No. of Cases | Primary FNAC Diagnosis | No. of Cases | No of HPE Cases | HPE Finding | ROM (%) |

| I (Non-Diagnostic) | 5 | Normal Salivary Gland Structures | 2 | 1 | Normal Salivary | 0 |

| Cystic Lesion | 3 | 3 | Gland Structures | |||

| II (Non Neoplastic) | 14 | Acute Sialadenitis | 2 | 0 | Benign Cystic Lesion | |

| Chronic Sialadenitis | 6 | 3 | 0 | |||

| Acute Supporative Lesion | 1 | 0 | Chronic Sialadenitis | |||

| Parotitis | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Sialoadenosis | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Retention Cyst | 1 | 1 | ||||

| III (AUS) | 4 | Chondroidmyxoid Stroma | 1 | 1 | Chronic sialadenitis | |

| Mucinous Cyst | 2 | 0 | MEC | 50 | ||

| Suspicious Looking Squamous cells | 1 | 1 | ||||

| IV-a (Benign Neoplasm) | 29 | Pleomorphic Adenoma | 28 | 9 | Metastatic SCC | |

| Basal cell Adenoma | 1 | 1 | Pleomorphic Adenoma | 0 | ||

| IV-b (SUMP) | 2 | Salivary Gland Neoplasm | 1 | 0 | Pleomorphic Adenoma | |

| D/D-Low Grade MEC Vs Warthin | 1 | 1 | 50 | |||

| V (SM) | 1 | Malignant Epithelial Lesion | 1 | 1 | MEC | |

| VI (Malignancy) | 2 | MEC high grade | 1 | 1 | Metastatic SCC | 100 |

| Salivary Duct Carcinoma | 1 | 0 | MEC | 50 |

AUS, Atypia of undetermined significance; SUMP, Salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential; MEC, Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma; SCC, Squamous cell Carcinoma

| Cytological category | No. of cases | Histopathological diagnosis | ROM (%) | |

| benign | malignant | |||

| I | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| II | 14 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| III | 4 | 0 | 2 | 50 |

| IV a | 29 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| IV b | 2 | 0 | 1 | 50 |

| V | 1 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| VI | 2 | 0 | 1 | 50 |

Category I consist of 5 cases, of which 3 had a primary cytologic diagnosis of the cystic lesion, which on histopathological examination were reported as a benign cystic lesion. Two cases on FNAC were reported as cytological features of normal salivary gland structures, and histopathological follow up was available only in one case, which reported the same. Risk of malignancy of category I was 0%. MSRSGC Category II had 14 cases with chronic sialadenitis as the commonest lesion. Histopathological follow up was available in 4 cases, of which 3 had a concordant diagnosis of chronic sialadenitis. However, on histopathological follow-up, one discordant case was noted that had a cytological diagnosis of retention cyst but was reported as chronic sialadenitis. The ROM of category II was 0%.

MSRSGC Category III had 4 cases. Two cases were reported as mucinous cysts on FNAC, but no histopathological follow up was available.

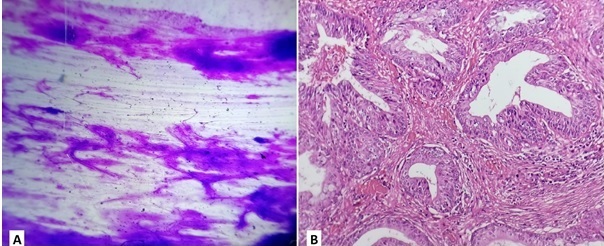

On histopathology, one case reported as chondromyxoid stroma only on FNAC was later reported as Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Micrographs Showing (A) FNAC of a Salivary Gland Lesion with Chondromyxoid Stroma only and Corresponding Tissue Section (B) Shows Picture of Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma with Cystic Spaces Lined by Mucoid, Squamous, and Intermediate Cells.

Another case reported as suspicious-looking squamous cells on cytology was later reported as metastatic squamous cell carcinoma on histopathology. ROM of category III was 50%.

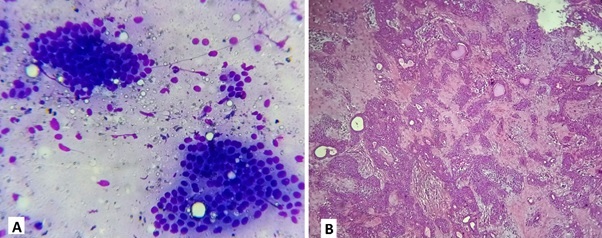

MSRSGC Category IVa had 29 cases with pleomorphic adenoma as the commonest tumour (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Micrographs Showing (A) FNAC Picture of Basal Cell Adenoma Showing Clusters of Small Basaloid Epithelial Cells with Scanty Cytoplasm and Bland rounded Nuclei, Peripheral Palisading of Cells with Inconspicuous Stroma; (B) Corresponding Tissue Section shows Pleomorphic Adenoma with Tubules Lines by Inner Layer of Ductal Cells and Outer Layer of Myoepithelial Cells of Variable Thickness Radiating into the Surrounding Myxoid Matrix.

Histopathological follow up was available in 10 cases. Nine were reported as pleomorphic adenoma on FNAC had a concordant diagnosis on histopathology. One case reported as monomorphic adenoma on FNAC had a discordant diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma on histopathology. The ROM was 0%.

There were two cases of MSRSGC Category IVb. One case was reported as salivary gland neoplasm, but no histopathological follow-up was available. Another case on FNAC was reported as the differential diagnosis of low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma versus warthin tumour. On histopathological follow-up, it was reported mucoepidermoid carcinoma. The ROM of MSRSGC Category IVb was 50%.

MSRSGC Category V had only one case reported as a malignant epithelial lesion on FNAC, and on histopathological follow-up, it was reported metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. The ROM of MSRSGC Category V was 100%.

MSRSGC Category VI had two cases. One case was reported as salivary duct carcinoma on FNAC, but no histopathological follow-up was available. Another case reported as high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma on FNAC was reported as mucoepidermoid carcinoma on histopathology. The ROM of MSRSGC Category VI is 50%. Table 4 depicts a comparison of ROM of the present study with published literature.

| Authors | ROM % of Milan Category | ||||||

| I | II | III | Iva | IV b | V | VI | |

| MSRSGC: Faquin et al. [11] | 25 | 10 | 20 | <5 | 35 | 60 | >90 |

| Karuna V et al. [12] | 0 | 0 | 50 | 2.44 | 33.33 | 100 | 93.33 |

| Wu H et al. [13] | 15 | 0 | 40 | 9.5 | 13.3 | 50 | 100 |

| Hollyfield J et al. [14] | 38 | 17 | 33 | 4 | 33 | 67 | 100 |

| Rohilla M et al. [15] | 0 | 17.4 | 100 | 7.3 | 50 | - | 96 |

| Jha S et al. [16] | 42.86 | 26.67 | 100 | 10.17 | 0 | 71.42 | 100 |

| Pujani M et al. [17] | 0 | 10 | 50 | 2.5 | 50 | 100 | 100 |

| Song S et al. [19] | 16.1 | 17.9 | 30.6 | 2.2 | 46.6 | 78.9 | 98.5 |

| Viswanathan K et al. [20] | 6.7 | 7.1 | 38.9 | 5 | 34.2 | 92.9 | 92.3 |

| Chen Y et al. [21] | 8.6 | 15.4 | 36.8 | 2.6 | 32.3 | 71.4 | 100 |

| present study | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 50 | 100 | 50 |

Statistical analysis revealed the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy as 75%, 100%, 100%, 95%, and 95.65%, respectively. Comparison of these statistical values with other published series are shown in Table 5.

| Authors | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV | NPV | Diagnostic Accuracy (%) |

| Karuna V et al. [12] | 85 | 98.14 | 94.44 | 94.64 | 94.59 |

| Wu H et al. [13] | 75 | 98.4 | 88.9 | 95.3 | |

| Rohilla M et al. [15] | 79.4 | 98.3 | 96.4 | 89.2 | 91.4 |

| Jha S et al. [16] | 64.28 | 97.01 | 90 | 86.67 | 87.37 |

| Pujani M et al. [17] | 81.8 | 100 | 100 | 96.4 | 96.9 |

| Viswanathan K et al. [20] | 79 | 98 | 92 | 94 | |

| Chen Y et al. [21] | 70.4 | 99.2 | 90.5 | 96.7 | 80.1 |

| present study | 75 | 100 | 100 | 95 | 95.65 |

Discussion

FNAC has been used widely for over five decades in the initial evaluation and triage of patients with salivary gland lesions [2-4]. MSRSGC is a newer tiered system for reporting salivary gland lesions according to risk stratification to provide better communication between clinicians and cytopathologists and ultimately improve patient care. Another advantage of this system is that it allows for estimates of ROM and reproducibility [8-11]. Our study attempts to determine the cytopathological spectrum of salivary gland lesions using the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland lesions in a tertiary care hospital of northeast India and study its clinical utility.

In our study, 57 salivary gland lesions were studied and reclassified using the MILAN system. Histopathological correlation was available for 23 cases.

There were 31 males (54.38%) and 26 females (45.6%) in our study, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.19:1. This is comparable with a few other published literature [12-16]. Our study population’s mean and median age was 35± 16 and 34 years (range 6-70 years). This is similar to the findings of some previously published reports [15-17].

The most frequent site of involvement in our study was the parotid gland (70.2%), followed by the submandibular gland (26.3%). The minor salivary gland was affected only in 3.5% of cases. Similar findings were recorded in a few reports published in the literature [14-19]. The percentage of non-diagnostic category cases in our study was 8.7%, similar to with available published literature [16, 19-20]. The non-diagnostic criteria were applied strictly according to published MSRSGC criteria. These are; less than 60 lesional cells, poorly prepared slides with artefacts precluding proper assessment, nonmucinous cyst contents or normal salivary gland elements in the setting of clinically or radiologically defined mass [11]. There were five cases in MSRSGC category I, of which 3 had a primary cytologic diagnosis of cystic lesion, which on histopathological examination were reported as a benign cystic lesion. Two cases on FNAC were reported as cytological features of normal salivary gland structures, and histopathological follow up was available only in one case, which reported the same. The percentage of the non-neoplastic category in our study is 24.6%. This is similar to studies done by Wu H, Jha S, Viswanathan K, Chen Y et al [13, 16, 20, 21]. Chronic sialadenitis was the commonest lesion diagnosed on cytology. Histopathological follow up was available on four cases, of which three had a concordant diagnosis of chronic sialadenitis. One discordant case had a cytological diagnosis of retention cyst, but histopathological follow-up was reported as chronic sialadenitis. Scant cellular content, mainly a few macrophages and a few epithelial cells, clear fluid on aspiration and complete collapse of the cyst following aspiration might be a possible reason for discordant diagnosis.

AUS is reserved for those lesions that exhibit morphologic overlap between non-neoplastic and neoplastic cases11. The percentage of the AUS category in our study was 7% which is similar to studies done by Leite A, Song S, Viswanathan K et al [18, 19, 20]. Two cases were reported as mucinous cysts on FNAC, but no histopathological follow up was available. One case reported as chondromyxoid stroma on FNAC was later reported as Mucoepidermoid carcinoma on histopathology. The presence of abundant chondromyxoid stroma with absent cellular material was categorized as AUS on FNAC. Another case reported suspicious-looking squamous cells on cytology led to categorization as AUS on FNAC. On histopathological follow-up, it was later reported as metastatic squamous cell carcinoma.

The percentage of benign category IV a in our study was the highest, 50.9%. Similar findings were noted in some published literature [16, 21]. Pleomorphic adenoma was the commonest salivary gland neoplasm (Figure 2). Histopathological follow up was available in 10 cases. Nine cases reported as pleomorphic adenoma on FNAC had a concordant diagnosis on histopathology. One case reported as basal cell adenoma on FNAC had a discordant diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma on histopathology. The absence of stromal components in the cytological smear may cause inconsistent diagnosis.

The diagnosis of SUMP is reserved for those salivary gland FNAs in which morphologic features are compatible with a neoplastic process but with a differential diagnosis that includes both benign and malignant entities [11]. One case was reported as salivary gland neoplasm, but no histopathological follow-up was available. Another case on FNAC revealed oncocytic cells, reactive lymphocytes, few squamous cells, mucin-producing goblet cells and cellular debris in a mucoid background. It was reported as a differential diagnosis of low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma versus warthin tumour on FNAC and categorized as SUMP based on MSRSGC. On histopathological follow-up, it was later reported mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

The diagnosis of suspicious for malignancy SM category is reserved for those salivary gland FNACs when overall cytologic features suggest malignancy; however, all the criteria for a specific diagnosis of malignancy are not present [11]. The percentage of cases of SM category in our study is 1.8 % which is similar to findings of studies done from various centres [17-21]. MSRSGC Category V had only one case reported as a malignant epithelial lesion on FNAC, and on histopathological follow-up, it was reported metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. Malignant category in MSRSGC includes those salivary gland FNAs which contain a combination of cytomorphologic features that either alone or in combination with ancillary studies is diagnostic of malignancy. The percentage of cases of malignant category in our study is 3.5% which is similar to studies done by Pujani M, Leite A, Chen Y et al [17, 18, 21]. MSRSGC Category VI had 2 cases. One case was reported as salivary duct carcinoma on FNAC, but no histopathological follow-up was available. Another case reported as high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma on FNAC was reported as mucoepidermoid carcinoma on histopathology.

The risk of malignancy reported in our study was 0%, 0%, 50%, 0%, 50%, 100% and 50%, respectively, for each category, and the results are comparable to that provided in the MSRSGC and recent other studies [11-17, 19-21].

The overall diagnostic accuracy of cytologic reporting of salivary gland lesions based on Milan nomenclature in our institution was 95.65%, comparable to that of other studies (80.1% – 96.9%) [12, 15-17, 21]. The sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values in our study for malignant diagnosis were 75%, 100%, 100%, and 95%, respectively. These figures were comparable with other studies. The slightly lower sensitivity in our study was probably due to the lower incidence of malignant cases reported in the patient population of our institution. Our findings reflect the positive contribution of the MSRSGC towards accurately identifying the malignant lesions and thus further helping the clinicians regarding the specific management decisions.

This series carries several limitations inherent with retrospective analysis. Moreover, there is a low sample size and fewer histopathological follow-ups. However, since the Milan system of reporting salivary gland cytopathology is a recently introduced classification scheme, it has not been adopted in many institutions, including ours. Hopefully, the Milan system will be widely utilized in reporting salivary gland cytopathology and more prospective data with a larger sample size will be available.

In conclusions, The tiered classification system of MSRSGC categorizes salivary gland lesions by associated management and malignancy risk rather than only attempting to recapitulate specific histopathologic diagnoses. The high sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of cytologic reporting of salivary gland lesions based on Milan nomenclature in our institution reflect the positive contribution of the MSRSGC towards accurately identifying the malignant lesions and thus further helping the clinicians regarding the specific management decisions. However, large scale multicentric prospective studies are needed before its reliability and validity are proven.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee of Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed Medical College, Assam 781301.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

None.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for- profit sectors.

References

- Salivary gland tumours. A review of 2410 cases with particular reference to histological types, site, age and sex distribution Eveson JW , Cawson RA . The Journal of Pathology.1985;146(1). CrossRef

- Cytologic Diagnosis on Aspirate from 1000 Salivary-Gland Tumours. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 1967;63(sup224):168-172. Eneroth C , Frazén S, Zajicek J. Acta Oto-Laryngologica.1967;63(sup224):168-172.

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: a systematic review Colella G, Cannavale R, Flamminio F, Foschini MP . Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: Official Journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons.2010;68(9). CrossRef

- Salivary gland FNA cytology: role as a triage tool and an approach to pitfalls in cytomorphology Mairembam P, Jay A, Beale T, Morley S, Vaz F, Kalavrezos N, Kocjan G. Cytopathology: Official Journal of the British Society for Clinical Cytology.2016;27(2). CrossRef

- Pitfalls in salivary gland fine-needle aspiration cytology: lessons from the College of American Pathologists Interlaboratory Comparison Program in Nongynecologic Cytology Hughes JH ., Volk EE , Wilbur DC . Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine.2005;129(1). CrossRef

- Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology: How Accurate Is It in the Diagnosis of Salivary Gland Malignancy, and What Are the Pitfalls? Modi M, Trivedi M, Nilkanthe R. American Journal of Clinical Pathology.2016;146(suppl_1):2.

- WHO classification of head and neck tumours El-Naggar AK, Chan JK, Grandis JR. 2017.

- Is it time to develop a tiered classification scheme for salivary gland fine-needle aspiration specimens? Baloch ZW , Faquin WC , LayfieldLJ . Diagnostic Cytopathology.2017;45(4). CrossRef

- Is it time we adopted a classification for parotid gland cytology? Bajwa MS , Mitchell DA , Brennan PA . The British Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery.2014;52(2). CrossRef

- The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: Analysis and suggestions of initial survey Rossi ED , Faquin WC , Baloch Z, Barkan GA , Foschini MP , Pusztaszeri M, Vielh P, Kurtycz DFI . Cancer Cytopathology.2017;125(10). CrossRef

- The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology Faquin W, Rossi E, Baloch Z, Barkan G, Foschini M, Kurtycz D, et al . 1st ed. springer.2018.

- Effectuation to Cognize malignancy risk and accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology in salivary gland using "Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology": A 2 years retrospective study in academic institution Karuna V, Gupta P, Rathi M, Grover K, Nigam JS , Verma N. Indian Journal of Pathology & Microbiology.2019;62(1). CrossRef

- Application of the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: A Retrospective 12-Year Bi-institutional Study Wu HH , Alruwaii F, Zeng BR , Cramer HM , Lai CR , Hang JF . American Journal of Clinical Pathology.2019;151(6). CrossRef

- Northern Italy in the American South: Assessing interobserver reliability within the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology Hollyfield JM , O'Connor SM , Maygarden SJ , Greene KG , Scanga LR , Tang S, Dodd LG , Wobker SE . Cancer Cytopathology.2018;126(6). CrossRef

- Three-year cytohistological correlation of salivary gland FNA cytology at a tertiary center with the application of the Milan system for risk stratification Rohilla M, Singh P, Rajwanshi A, Gupta N, Srinivasan R, Dey P, Vashishta RK . Cancer Cytopathology.2017;125(10). CrossRef

- The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: Assessment of Cytohistological Concordance and Risk of Malignancy Jha S, Mitra S, Purkait S, Adhya AK . Acta Cytologica.2021;65(1). CrossRef

- A critical appraisal of the Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytology (MSRSGC) with histological correlation over a 3-year period: Indian scenario Pujani M, Chauhan V, Agarwal C, Raychaudhuri S, Singh K. Diagnostic Cytopathology.2019;47(5). CrossRef

- Retrospective application of the Milan System for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: A Cancer Center experience Leite AA , Vargas PA , Dos Santos Silva AR , Galvis MM , Sá RS , Lopes Pinto CA , Kowalski LP , Saieg M. Diagnostic Cytopathology.2020;48(9). CrossRef

- The utility of the Milan System as a risk stratification tool for salivary gland fine needle aspiration cytology specimens Song SJ , Shafique K, Wong LQ , LiVolsi VA , Montone KT , Baloch Z. Cytopathology: Official Journal of the British Society for Clinical Cytology.2019;30(1). CrossRef

- The role of the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: A 5-year institutional experience Viswanathan K, Sung S, Scognamiglio T, Yang GCH , Siddiqui MT , Rao RA . Cancer Cytopathology.2018;126(8). CrossRef

- Application of the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: A retrospective study in a tertiary institute Chen YA , Wu CY , Yang CS . Diagnostic Cytopathology.2019;47(11). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2023

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times