Exploring the Role of Online Psycho-Oncology Counseling Interventions in Alleviating Distress among Cancer Patients

Download

Abstract

Objective: This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the Online Psycho-Oncology Counseling (OPC) in reducing distress levels among cancer patients.

Methods: The research employs a paired sample t-test analysis to compare distress scores before and after the intervention. The study includes 30 solid tumor patients aged 30-59, undergoing cancer treatment. Distress levels were measured using the Distress Thermometer before and after the OPC intervention. Paired distress scores were computed for each participant, and a paired sample t-test was conducted to assess the statistical significance of the observed changes.

Result: A statistically significant reduction in distress scores post-OPC intervention (t-value = 3.657, df = 29, p < 0.05) was observed. The mean distress score decreased from 5.67 ± 1.093 before OPC to 4.77 ± 1.675 after OPC. Importantly, 26.6% of participants shifted from high to low distress levels. The findings suggest that the Online Psycho-Oncology Intervention is effective in alleviating distress among cancer patients. The paired sample t-test provides robust statistical evidence supporting the positive impact of OPC on psychological well-being. Additionally, semi structured interview schedule was followed to explore the feasibility and satisfaction of the OPC program. Likert scale and thematic analysis was followed to analyze the qualitative data.

Conclusion: Further research with larger cohorts and extended follow-up periods is recommended to enhance the understanding of the long-term effectiveness of psycho-oncology interventions in the digital realm.

Introduction

Cancer diagnosis constitutes a life-altering event, imposing not only physical challenges but also profound psychological effects on individuals. Patients grappling with cancer often exhibit elevated rates of psychiatric disorders, with depression being a predominant manifestation alongside anxiety, adjustment disorders, delirium, and substance-related disorders [1]. Recognizing the urgent need for diagnosis and intervention, particularly in the realm of psychiatric distress, becomes imperative. Distress, in the context of cancer, is characterized as a multifactorial and unpleasant emotional experience that spans cognitive, behavioral, emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions, potentially hindering coping mechanisms throughout the cancer trajectory [2]. Studies indicate that a significant proportion, ranging from 30% to 50%, of cancer patients experience distress across various phases of their illness [3, 4]. The management of the adverse impact of cancer on mental health has ascended in priority, given its undeniable influence on both psychological well- being and physical health [5].

Addressing this burgeoning concern, psycho-oncology intervention (PI) emerges as a pivotal strategy not only for enhancing well-being but also as a potential safeguard against relapse and symptom exacerbation [5]. Recent findings underscore the efficacy of PI in diminishing emotional distress among cancer patients, shedding light on its role in improving overall quality of life [6]. However, the integration of routine distress screening, often constrained by manpower limitations and a surge in patient loads, remains challenging in traditional clinical settings [7, 8].

In response to these challenges, this study explores the adoption of digital approaches, specifically Online Psycho-Oncology Counseling (OPC), as a complementary strategy to bolster existing psycho-oncological support for cancer patients. The advantages of cost-efficiency, high accessibility, and flexibility inherent in digital interventions hold promise for overcoming existing barriers and reaching underserved populations [5]. This investigation aims to analyze the impact of OPC on distress levels among cancer patients, considering its potential to address the unique needs of this population and contribute to an enhanced quality of life throughout their cancer journey. Additionally, the study includes the evaluation of the feasibility and satisfaction of the OPC program.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This interventional study involved experimental pre-post design to understand the OPC on the cancer patients to reduce the distress among the cancer patients Assessment of feasibility and satisfaction of online Psycho-oncology intervention counseling among cancer patients conducted between November, 2023 – January, 2024.

Study Setting

The study was conducted at 4baseCare, an Illumina Accelerator Company specializing in precision oncology, utilizing advanced genomics to personalize patient care, offering services like Genetic Counseling and Onco Diet consultations through the innovative Oncobuddy platform. The study is conducted through Oncobuddy, a 360-degree digital healthcare platform developed by 4baseCare oncosolutions private limited. This platform serves as a unified and patient-centric ecosystem, providing comprehensive support to patients in their battle against cancer. Through Oncobuddy, patients can avail consultations with Psycho-Oncologists, Oncologists, and other supportive care services through both video and audio calls.

Referral Process

The referral process commences after the collection of blood samples for genetic analysis. Care companions or coordinators, acting as liaisons between patients and services, contact patients to explain the available supportive care services, including Psycho-Oncology, Diet Counseling, and Genetic Counseling. Patients opting for these services are seamlessly referred to either Psycho- Oncology, Diet Counseling, or Genetic Counseling based on their preferences.

Psycho-Oncology Sessions

Care companions schedule psycho-oncology sessions based on patient and psycho-oncologist availability through Oncobuddy or Google Meet. Sessions are scheduled based on patient language preferences, with the lead consultant, proficient in Bengali, English, and Hindi. The documentation of interventions and psycho-social concerns for each patient is maintained by the psycho-oncologist. Patient medical reports are uploaded to Google Drive, enabling psycho-oncologists to review medical summaries and reports before counseling sessions. Psycho-Oncology interventions are based on existing publications on the cancer population, ensuring evidence-based and patient-tailored strategies.

The first online session, lasting 45 to 60 minutes, involve rapport establishment, self-introduction, discussion of current health, distress assessment, problem list assessment, and verbal psychological recommendations. Interventions are uploaded on Oncobuddy, allowing patients to access and download recommendations at any time. The importance of following psychological recommendations is explained, and patients are informed about the next follow-up call scheduled after one month. Care companions provide the first follow-up date after one month based on patients’ availability, with reminder calls two days and one day prior to the session. A brief follow-up session assesses distress levels, patient adherence to interventions, and satisfaction with the initial psycho-oncology counseling.

Participants

The study included 30 patients diagnosed with solid tumors undergoing cancer treatment, aged between 30 – 59 years, who have enrolled with 4basecare for support services between November 2023 and December 2023. The Online Psycho-Oncology Counseling (OPC) was administered to patients with a distress score equal to or greater than 4. The intervention, encompassing counselling on four key themes, addressed prevalent issues among participants. Patients on psychiatric medications and in hospice care were excluded from the study.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

Patients’ gender, marital status, employment and hobbies were documented.

Medical characteristics

Data about the diagnosis and treatment of the initial cancer was obtained from 4baseCare patient master sheet which contained detailed information about diagnosis and treatment.

Distress

Distress was measured using the Distress Thermometer (DT) [6]. DT is a screening tool, on which cancer patients can indicate their overall distress (physical, emotional, social, as well as practical). Higher scores indicate more distress. The DT is a quick screening tool that accurately identifies distress in cancer patients [6]. Another measure was the Problem Checklist (PL) of the patient was documented. Both DT and PL are well-validated and mandated screening tools. Patients are requested to rate their distress on a scale ranging between 0 -10 (0 - no distress; 10 - extreme distress). Patients scored below 4 were excluded from the study. Cancer patients enrolled for the program were requested to fill an DT and PL questionnaire. Patients were included based on the distress score; patients scored below 4 were excluded from the study.

Online Psycho-oncology Intervention

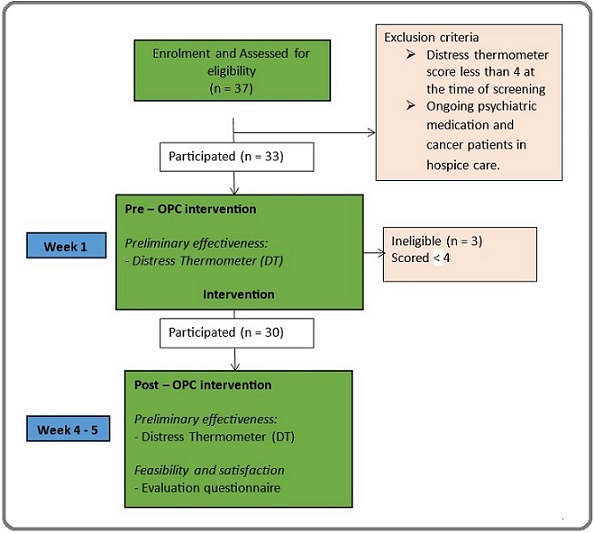

Psycho oncology counseling sessions for all participants were conducted online. It included a generic approach to improve coping with current or future challenges of illness and preventing or reducing psychosocial problems, e.g. (health) anxiety or difficulties in relationships (family, friends and colleagues). The intervention process is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Intervention Process Flowchart.

The first session of OPC lasts for 45 to 60 minutes. The follow up sessions are conducted after 4-5 weeks, for about 30 minutes.

Patients in the first session after DT assessment, psycho-oncologist discussed the ways to alleviate stress. Four PIs, namely 1. Improving energy and interest in physical activity 2. Cognitive restructuring and relaxation strategies 3. Improving sleep pattern and 4. Enhance family dynamics with the aim of helping the patients reduce distress was explained in detail. The PIs were composed by senior psycho-oncologist of 4basecare Bengaluru, who had knowledge and experience for managing the psychosocial consequences among cancer patients. All PIs remain accessible. To close the session, patients were reminded to adhere to respective PIs for the next one month. Patients were also requested to ask any question that was left unanswered during the session. After one month post – OPC intervention follow-up session was conducted. At post – OPC intervention, DT and feasibility and satisfaction questionnaire was administered to understand the effectiveness of OPC.

Specific intervention areas identified as crucial by psycho-oncologists for participants undergoing cancer treatment are outlined in Table 1.

| Intervention | N | (%) |

| Cognitive restructuring and relaxation | 28 | (93.33) |

| Lack of energy and interest in physical activity | 24 | (80.66) |

| Disturbed/ intermittent sleep pattern | 23 | (76.66) |

| Poor family dynamics | 11 | (36.66) |

The majority of participants (93.33%) were identified by psycho-oncologists as requiring interventions in cognitive restructuring and relaxation techniques. Psycho-oncologist identified 80.66% of participants as needing interventions addressing the lack of energy and interest in physical activities. A considerable percentage of participants (76.66%) were identified as experiencing issues with disturbed or intermittent sleep patterns. About 36.66% of participants were in need of interventions related to poor family dynamics.

Feasibility and Satisfaction

After the PI, an evaluation questionnaire was used to assess Feasibility and satisfaction with the OPC in post – OPC intervention. Patients were asked to give the OPC an overall grade on a 5-point Likert-scale (1-5). They were asked to indicate their level of comfort with the duration of the session on a 3-point Likert-scale (1-3). The extent of PI followed by the patients were assessed on a 3-point Likert-scale (1-3). The reasons for following and not following PI were explored using one open-ended question. Furthermore, patients’ willingness to recommend PI to other cancer patients were assessed using a 3-point Likert-scale (1-3).

Questions regarding feasibility and satisfaction included are as: “Were you able to follow PI in the last one month”? and “Would you recommend OPC to other cancer patients”? Likert scale was used to obtain the response from participants at post – OPC intervention.

Two Open-ended questions were also included. Thematic analysis was followed to analyze the data. Qualitative responses were recoded and transferred into quantitative variables into frequencies. The reasons for the same were also explored using an open-ended question.

Data Analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26 (IBM Corporation, NY). Descriptive statistics were employed to provide a comprehensive overview of participants’ socio-demographic and medical characteristics. The feasibility and satisfaction of the Online Psycho-Oncology Intervention (OPC) were assessed using descriptive statistics. Additionally, a thematic analysis was applied to qualitative data gathered from the feasibility and satisfaction scale. To explore the preliminary effectiveness of the intervention, differences in distress scores between pre and post-intervention were examined using parametric tests, specifically the Paired T-Test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 to determine the presence of meaningful differences.

Results

The study, encompassing 30 cancer patients, revealed a predominantly female and married cohort (70% and 96.67%, respectively), with a mean age of 47.73 ± 9.30 years. Employment distribution highlighted 43.33% engaged in paid occupations (Table 2).

| Socio-demographic Characteristics | N | (%) |

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 47.73 ± 9.30 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 9 | (30.00) |

| Female | 21 | (70.00) |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 1 | (3.33) |

| Married | 29 | (96.67) |

| Employment status | ||

| Paid occupation | 13 | (43.33) |

| No paid occupation | 17 | (56.67) |

Table 3 presents the medical characteristics of cancer patients enrolled in the OPC program.

| Medical characteristics | N | (%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) (Mean ± SD) | 46.05 ± 9.35 | |

| Time since diagnosis (years) (Mean ± SD) | 19.43 ± 25.19 | |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Breast cancers | 11 | (36.67) |

| Pancreas cancers | 3 | (10) |

| Colon cancer | 3 | (10) |

| Ovary cancer | 3 | (10) |

| Stomach cancer | 2 | (6.67) |

| Gall bladder | 2 | (6.67) |

| Lung cancer | 1 | (3.33) |

| Anal canal cancer | 1 | (3.33) |

| Oesophagus cancer | 1 | (3.33) |

| Liver cancer | 1 | (3.33) |

| Uterus cancer | 1 | (3.33) |

| Kidney cancer | 1 | (3.33) |

| Treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy | 28 | (93.33) |

| Surgery | 12 | (40) |

| Targeted therapy | 4 | (13.33) |

| Radiation therapy | 3 | (10) |

| Hormone therapy | 2 | (6.67) |

| Oral chemotherapy | 2 | (6.67) |

| Immunotherapy | 1 | (3.33) |

| Ayurvedic treatment | 1 | (3.33) |

The cohort, with a mean age at diagnosis of 46.05 ± 9.35 years, demonstrated a diverse range of cancer types, with breast cancer being the most prevalent (36.67%). The mean time since diagnosis was 19.43 ± 25.19 months. Predominantly, patients underwent chemotherapy (93.33%), surgery (40%), and targeted therapy (13.33%) as part of their treatment modalities.

Along with the distress thermometer (DT) cancer patients were assessed for their physical, emotional, social, practical and spiritual or religious concerns.

Table 4 reveals significant challenges faced by patients with high distress levels.

| Problems | Yes | No | ||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Physical concerns | ||||

| Pain | 17 | (56.7) | 13 | (43.3) |

| Sleep | 23 | (76.7) | 7 | (23.3) |

| Fatigue | 24 | (80) | 6 | (20) |

| Tobacco use | - | 30 | (100) | |

| Substance use | - | 30 | (100) | |

| Memory or concentration | 8 | (26.7) | 22 | (73.3) |

| Sexual health | 9 | (30) | 21 | (70) |

| Change in eating | 22 | (73.3) | 8 | (26.7) |

| Loss or change of physical abilities | 21 | (70) | 9 | (30) |

| Emotional Concerns | ||||

| Worry or anxiety | 24 | (80) | 6 | (20) |

| Sadness or depression | 14 | (46.7) | 16 | (53.3) |

| Loss of interest or enjoyment | 11 | (36.7) | 19 | (63.3) |

| Grief or loss | 1 | (3.3) | 29 | (96.7) |

| Fear | 19 | (63.3) | 11 | (36.7) |

| Loneliness | 9 | (30) | 21 | (70) |

| Anger | 16 | (53.3) | 14 | (46.7) |

| Changes in appearance | 22 | (73.3) | 8 | (26.7) |

| Feeling of worthlessness or being a burden | 19 | (63.3) | 11 | (36.7) |

| Social Concerns | ||||

| Relationship with spouse or partner | 9 | (30) | 21 | (70) |

| Relationship with children | 3 | (10) | 27 | (90) |

| Relationship with family members | 11 | (36.7) | 19 | (63.3) |

| Relationship with friends or co workers | 3 | (10) | 27 | (90) |

| Communication with health care team | 2 | (6.7) | 28 | (93.3) |

| Ability to have children | 1 | (3.3) | 29 | (96.7) |

| Prejudice or discrimination | 3 | (10) | 27 | (90) |

| Practical Concerns | ||||

| Taking care of myself | 14 | (46.7) | 16 | (53.3) |

| Taking care of others | 16 | (53.3) | 14 | (46.7) |

| Work | 7 | (23.3) | 23 | (76.7) |

| School | - | 30 | (100) | |

| Housing | 2 | (6.7) | 28 | (93.3) |

| Finances | 17 | (56.7) | 13 | (43.3) |

| Insurance | 26 | (86.7) | 4 | (13.3) |

| Transportation | 2 | (6.7) | 28 | (93.3) |

| Child care | - | 30 | (100) | |

| Having enough food | 17 | (56.7) | 13 | (43.3) |

| Access to medicine | - | 30 | (100) | |

| Treatment decisions | 2 | (6.7) | 28 | (93.3) |

| Spiritual or Religious Concerns | ||||

| Sense of meaning or purpose | 18 | (60) | 12 | (40) |

| Changes in faith or beliefs | 3 | (10) | 27 | (90) |

| Death, dying, or afterlife | 4 | (13.3) | 26 | (86.7) |

| Spiritual or Religious Concerns | ||||

| Conflict between beliefs and cancer treatments | 5 | (16.7) | 25 | (83.3) |

| Relationship with the sacred | 7 | (23.3) | 23 | (76.7) |

| Ritual or dietary needs | 6 | (20) | 24 | (80) |

Among the physical concerns, a notable majority experience pain (56.7%), sleep disturbances (76.7%), fatigue (80.0%), and alterations in eating patterns (73.3%). Emotionally, patients report high levels of worry or anxiety (80.0%) and varying degrees of sadness or depression (46.7%). Socially, relationship strains with spouses or partners (30.0%) and family members (36.7%) are evident. Practical concerns encompass financial challenges (56.7%), insurance issues (86.7%), and transportation difficulties (6.7%). Spiritually, patients grapple with a search for meaning or purpose (60.0%), changes in faith or beliefs (33.3%), and considerations related to death, dying, or the afterlife (13.3%). These findings highlight the multidimensional nature of distress, emphasizing the need for comprehensive support approaches.

Table 5 illustrates the evaluation of the Online Psycho-Oncology (OPC) intervention by comparing distress scores before and after the intervention.

| Test | Distress Score | t – value | P value |

| Pre – OPC intervention | 5.67 ± 1.093 | 3.657 | 0.001 |

| Post – OPC intervention | 4.77 ± 1.675 |

The pre-OPC intervention distress score was 5.67 ± 1.093, and the post-OPC intervention distress score was 4.77 ± 1.675. The statistical analysis, with a t-value of 3.657 and a p-value of less than 0.001, indicates a significant reduction in distress scores after the OPC intervention.

The post-test results indicate a positive change in distress levels. After the OPC program, 26.66% (n=8) of the patients shifted from the high distress category to the low distress category. 73.34% (n=22) of patients still reported high distress after the intervention.

Feasibility and satisfaction of the OPC intervention/ program

Cancer patients were assessed on the OPC intervention after one month. The results of the responses are tabulated in Table 6.

| Theme | N | (%) |

| Satisfaction with the counselling session | ||

| Completely disagree | - | |

| Disagree | - | |

| Not agree, not disagree | - | |

| Agree | 17 | (56.67) |

| Completely agree | 13 | (43.33) |

| Duration of the session | ||

| Too short | - | |

| Good | 28 | (93.33) |

| Too long | 2 | (6.67) |

| Could you follow psychological Interventions in the last one month? | ||

| Yes | 4 | (13.33) |

| No | - | |

| To certain extent | 26 | (86.67) |

| Reasons you could follow the psychological interventions | ||

| Theme | ||

| Trustworthiness and Credibility of the counselling | 25 | (83.33) |

| Delivery module | 25 | (83.33) |

| Usefulness | 22 | (73.33) |

| Delivery module | 20 | (66.66) |

| Would you recommend psychological Counselling to other cancer patients? | ||

| Surely | 27 | (90) |

| May be | 3 | (10) |

| No | - | |

| Reasons you would like to recommend psychological interventions to other cancer patients | ||

| Theme | ||

| The Flexibility of Online Counselling | 27 | (90) |

| Trustworthiness and Credibility of the counselling | 25 | (83.33) |

| Unavailability of psycho-oncology services at hospital | 25 | (83.33) |

| Improvement in symptoms | 24 | (80) |

Patients rated satisfactory and feasibility of OPC in terms of their counseling experiences as well as on the content. Thirteen percent and 56.67% of the patients felt satisfied with the OPC intervention. Regarding the duration of the session only 6.67% felt that the session was too long while 93.33% felt good. All the participants were satisfied and found the interventions to be feasible. Four patients (13.33%) and 26 (86.67%) patients could follow the PI “Yes” and “To a certain extent” consequently in between pre and post OPC intervention.

The qualitative data from thematic analysis shows that our participants could follow the PI in between pre and post mostly because of Trustworthiness and Credibility of the counseling (n=25, 83.33%): “I knew I have received the right recommendations from the right expert” and techniques of Delivery module. For “All the interventions were orally discussed and then uploaded in PDF document. I could access it easily anytime” was 83.33% (n=25). Twenty – two (73.33%) could find the usefulness with time: “Initially I was not sure that I will be able to do it, but slowly I could understand the improvement”. Twenty (66.66%) patients mentioned the theme of less difficulty level: “Techniques discussed were simple and easy”.

All the patients reported Psycho oncology counseling should be recommended to each cancer patient (Surely – 90%, may be – 10%).

Participants have reported Flexibility of OPC: Ninety percent of the patients felt “Spending time in hospital for a long time is always exhausting. Patients can join from home only. Online sessions can be rescheduled easily” with regard to flexibility of online counselling theme and Improvement in symptoms: “I am feeling better now and more confident. I am sure others will be getting the same result” by 80% of the patients. Twenty – five patients (83.33%) for the themes such as Trustworthiness and Credibility of the counseling and Unavailability of psycho- oncology services at hospital: “At most hospital psycho oncology facilities are not available and most of us are not aware about it” was reported.

Discussion

Understanding and addressing the distress experienced by cancer patients is pivotal in developing effective interventions within the realm of psycho-oncology. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of Online Psycho-Oncology (OPC) as an intervention in alleviating distress among cancer patients.

In a study, cancer patients’ distress was assessed using the Distress Thermometer (DT) and Problem List (PL) by NCCN, revealing prevalent concerns such as fears, worry, and fatigue. Our study aligns with these findings, highlighting “fatigue,” “anxiety,” and “changes in appearance” as predominant concerns among the cohort [11].

Focusing on individuals aged 30-59, this study revealed a high distress level of 73.3% even after the intervention, emphasizing a significant prevalence of distress within this age group. This aligns with existing literature reporting distress rates ranging from 30% to 60% [7, 8]. Early diagnosis of distress, coupled with interventions, has shown positive outcomes in improving the quality of life and treatment results for cancer patients [9, 10].

Noteworthy is the decline in distress scores observed post-implementation of the OPC intervention. This ground breaking aspect of our study, being the first to conduct online sessions for cancer patients and report a significant reduction in distress levels, underscores the potential of online interventions in enhancing the psychological well-being of cancer patients, marking a significant advancement in psycho-oncology.

Studies involving advanced cancer patients, have demonstrated positive outcomes with psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, in reducing fatigue and enhancing quality of life.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has also shown sustained improvements in psychological distress, fatigue, spiritual well-being, and overall quality of life [11-16].

The virtual format of our psycho-oncology counseling program may have contributed to the success of our study by overcoming logistical barriers, providing a sense of anonymity and privacy, and offering greater flexibility in scheduling. These advantages likely played a significant role in minimizing dropout rates and ensuring consistent participation in follow-up sessions.

Despite these contributions, certain limitations must be acknowledged, including the absence of a control group and the measurement of effects within a one-month post-intervention timeframe with a limited sample size. Future research will address these limitations by employing larger cohorts to enhance statistical measures. The promise demonstrated by OPC for patients suggests the need for ongoing development and continuous follow-up at specific intervals to optimize the efficacy and alignment of psycho-oncology interventions with evolving patient needs. Comprehensive follow-up procedures will provide a more in-depth understanding of the long-term outcomes and effectiveness of psycho-oncology interventions.

In conclusion, the study highlights the transformative potential of digital interventions in the field of psycho- oncology, offering new avenues for providing accessible and effective support to individuals navigating the challenges of cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the Cancer patients for their participation in the study.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for- profit sectors.

Declarations of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. The contents of this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the organization (s) the authors are affiliated to.

References

- Web-based MINDfulness and Skills-based distress reduction in cancer (MINDS): study protocol for a multicentre observational healthcare study Bäuerle A, Teufel M, Schug C, Skoda E, Beckmann M, Schäffeler N, Junne F, et al . BMJ open.2020;10(8). CrossRef

- Prevalence of psychosocial distress in cancer patients across 55 North American cancer centers Carlson LE , Zelinski EL , Toivonen KI , Sundstrom L, Jobin CT , Damaskos P, Zebrack B. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology.2019;37(1). CrossRef

- Stress and cancer: mechanisms, significance and future directions Eckerling A, Ricon-Becker I, Sorski L, Sandbank E, Ben-Eliyahu S. Nature Reviews. Cancer.2021;21(12). CrossRef

- Screening for psychosocial distress among patients with cancer: implications for clinical practice, healthcare policy, and dissemination to enhance cancer survivorship Ehlers Sl , Davis K, Bluethmann SM , Quintiliani LM , Kendall J , Ratwani RM , Diefenbach MA , Graves KD . Translational behavioral medicine.2019;9(2). CrossRef

- Psychiatric Symptoms and Psychosocial Problems in Patients with Breast Cancer İzci F, İlgün AS , Fındıklı E, Özmen V. The Journal of Breast Health.2016;12(3). CrossRef

- What do 1281 distress screeners tell us about cancer patients in a community cancer center? Kendall J, Glaze K, Oakland S, Hansen J, Parry C. Psycho-Oncology.2011;20(6). CrossRef

- Screening for psychological distress in follow-up care to identify head and neck cancer patients with untreated distress Krebber AH , Jansen F, Cuijpers P, Leemans CR , Verdonck-de Leeuw IM . Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer.2016;24(6). CrossRef

- Impact of Onset of Psychiatric Disorders and Psychiatric Treatment on Mortality Among Patients with Cancer Lee SA , Nam CM , Kim YH , Kim TH , Jang S, Park E. The Oncologist.2020;25(4). CrossRef

- Perceived stress is associated with a higher symptom burden in cancer survivors Mazor M, Paul SM , Chesney MA , Chen L, Smoot B, Topp K, Conley YP , Levine JD , Miaskowski C. Cancer.2019;125(24). CrossRef

- Cancer patients' emotional distress, coping styles and perception of doctor-patient interaction in European cancer settings Meggiolaro E, Berardi MA , Andritsch E, Nanni MG , Sirgo A, Samorì E, et al . Palliative & Supportive Care.2016;14(3). CrossRef

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Psychological Distress, Fear of Cancer Recurrence, Fatigue, Spiritual Well-Being, and Quality of Life in Patients With Breast Cancer-A Randomized Controlled Trial Park S, Sato Y, Takita Y, Tamura N, Ninomiya A, Kosugi T, Sado M, et al . Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.2020;60(2). CrossRef

- Psychological Distress in a Sample of Inpatients With Mixed Cancer-A Cross-Sectional Study of Routine Clinical Data Peters L, Brederecke J, Franzke A, Zwaan M, Zimmermann T. Frontiers in Psychology.2020;11. CrossRef

- Cognitive behavioral therapy or graded exercise therapy compared with usual care for severe fatigue in patients with advanced cancer during treatment: a randomized controlled trial Poort H, Peters M. E. W. J., Graaf W. T. A., Nieuwkerk P. T., Wouw A. J., Nijhuis-van der Sanden M. W. G., Bleijenberg G., Verhagen C. a. H. H. V. M., Knoop H.. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology.2020;31(1). CrossRef

- NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Distress Management, Version 2.2023 Riba MB , Donovan KZ , Ahmed K, Andersen B, Braun I, Breitbart WS , Brewer BW , et al . Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN.2023;21(5). CrossRef

- Distress Management, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Riba MB , Donovan KA , Andersen B, Braun I, Breitbart WS , Brewer BM , Buchmann LO , et al . Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN.2019;17(10). CrossRef

- The effectiveness of three mobile-based psychological interventions in reducing psychological distress and preventing stress-related changes in the psycho-neuro-endocrine-immune network in breast cancer survivors: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial Světlák M, Malatincová T, Halámková J, Barešová Z, Lekárová M, Vigašová D, Slezáčková A, et al . Internet Interventions.2023;32. CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2024

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times