Pharmacogenomic Profiling of DPYD Mutations and Genotype‑guided Dose Adjustment to Prevent Fluoropyrimidine Toxicity in Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients: A Real‑world Study from North India

Download

Abstract

Purpose: To quantify the prevalence of clinically actionable DPYD variants in North‑Indian gastrointestinal (GI) cancer patients and to evaluate whether Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)‑guided fluoropyrimidine dose attenuation mitigates early chemotherapy toxicity.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed 66 adults treated between January 2021 and December 2024 who underwent prescriptive DPYD genotyping for *DPYD* *2A*, c.2846A>T, *9A* (c.85T>C) and *13*. Fluoropyrimidine doses were modified according to CPIC activity‑score algorithms (25–50 % reduction for scores 1.5–1.0; ≥ 50 % reduction or avoidance for ≤ 0.5). Variant frequency was the primary end‑point; grade ≥ 3 toxicity within two cycles served as the secondary end‑point. Multivariable logistic regression identified independent predictors of toxicity.

Results: Actionable variants were detected in 32/66 patients (48.5 %), dominated by *DPYD* *9A* (43.9 %). All carriers received genotype‑guided dose reduction. Overall grade ≥ 3 toxicity occurred in 13/66 patients (19.7 %): 17.6 % of wild‑type versus 21.9 % of variant carriers (P = 0.28). After adjustment, toxicity rates across gastrointestinal, hematological, and dermatological domains remained comparable. Diabetes mellitus emerged as the sole independent predictor of grade ≥ 3 toxicity (adjusted odds ratio 5.99, 95 % CI 1.19–30.3; P = 0.03).

Conclusion: Almost half of North‑Indian GI‑cancer patients harbor an actionable *DPYD* variant—chiefly *9A*. Implementing CPIC‑based dose reduction neutralized variant‑linked excess risk of early severe toxicity, underscoring the clinical utility of routine DPYD genotyping and personalized fluoropyrimidine dosing. Enhanced vigilance is warranted for diabetic patients, who remain at heightened toxicity risk despite pharmacogenomic tailoring.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers represent a significant and escalating public health challenge in India. Recent data from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) indicate a projected increase in cancer incidence from 1.46 million cases in 2022 to 1.57 million by 2025, with GI cancer constituting approximately 25% of these cases [1].

Fluoropyrimidine‑based combination chemotherapy is a cornerstone in the treatment of GI cancer. These regimes often pair fluoropyrimidine‑such as 5‑flurouracil (5‑ FU), capecitabine – with other agents like platinum compound (e.g. cisplatin, oxaliplatin), irinotecan or targeted therapies to enhance efficiency. Dihydropyridine dehydrogenase (DPD) gene is the rate‑limiting enzyme responsible for metabolism of 5‑FU [2]. Point mutations in DPD gene can lead to varying functional forms of DPD gene. Homozygous or heterozygous mutations affecting DPD gene activity can lead to increased toxicity of 5‑FU by altering its metabolism [3]. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) have released guidelines recommending reducing the dose of 5‑FU in patients with these genomic alterations based on calculation of activity score (DPYD‑AS score) [3]. Given the genetic diversity of Indian population, the frequency of these variants may differ across regions. A recent study from South India reported a 12.5% prevalence of DPYD variants, highlighting regional variation [4, 5]. We recently have started doing DPD gene mutation testing in our hospital.

Pharmacogenomic profiling‑the study of how genetic variations affect an individual’s response to drugs‑has emerged as a key strategy in precision oncology. By identifying high risk genetic variants before initiating treatment, clinicians can tailor chemotherapy doses to minimize toxicity and improve outcome. For example, a large Indian cohort study using the Infinium Global Screening Array identified several clinically significant DPYD variants, including C29R and V7321, which are known to impair fluoropyrimidines metabolism and increase toxicity risk [6]. Additionally, a prospective European study of over 1100 patients demonstrated that genotype‑guided dosing significantly reduced severe toxicity in patients carrying DPYD mutations [6]. Despite such global progress, North India data on DPYD mutation prevalence and its clinical relevance remain scare.

The primary objective of our study is to estimate the prevalence of DPYD deficiency among patients scheduled to receive fluoropyrimidine‑based combination chemotherapy for GI cancer. The secondary objective is to assess the toxicity profile in a subset of DPYD mutant patients who underwent appropriate dose reduction based on DPYD‑AS score as per CPIC guidelines.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This was a descriptive retrospective observational study conducted at a tertiary care oncology centre in North India. The study included patients with histologically confirmed GI malignancies who were registered at our hospital and were planned to receive fluoropyrimidine‑ based combination chemotherapy and underwent DPYD mutation testing between Jan 2021 to dec 2024. This manuscript adheres to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines. A completed checklist is provided as Supplementary File 1.

Sample size

Assumptions: Confidence Level = 95%

Precision (d) = ± 9%

For estimation of sample size, the following formula has been used

n = (Z2α X P X (1‑P))/d2

Where;

Zα = Value of standard normal variate corresponding to α level of significance

P = Likely value of parameter (12.5%) [4].

Q = 1 – P

d = Margin of errors which is a measure of precision

With these assumptions the sample size works out as 52.We included our first 66 patients in our study.

Study Population

Inclusion criteria:

• Adult patients (≥ 18 years) with GI cancer (e.g. colorectal, gastric, pancreatic).

• Planned for treatment with 5‑Flurouracil (5‑FU), capecitabine or S‑1 in combination regime.

• Underwent DPYD mutation analysis prior to or during the first chemotherapy cycle.

• Availability of complete clinical records including chemotherapy regime, dosing, and toxicity.

Exclusion criteria

• Patients who received fluoropyrimidines‑based chemotherapy without DPYD testing.

• Incomplete clinical or follow up data

• Known contraindication to chemotherapy.

Consecutive patients were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

DPYD Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples using standard protocols. DPYD gene mutation analysis focused on known clinically relevant variants recommended by CPIC and widely reported in literature, including:

• DPYD*2A(c.1905+1G>A)

• DPYD*2A c.2846(A>T) p.D949V

• DPYD*9A c.85(T>c) P.C29R

• DPYD*13 c.1679 (T>G) p.I560s

Mutation testing was performed using PCR‑based assay in hospitals molecular diagnostic laboratory. The DNA extraction process used Qiagen DNAMini Kit to maintain purity levels (A260/A280 ratio 1.8– 2.0). The NABL‑accredited laboratory performed mutation testing through CE‑IVD marked PCR assays for DPYD2A, c.2846A>T, DPYD9A (c.85T>C), and DPYD13. The testing process included known wild‑type and mutant controls in each batch. The molecular pathologist checked the results twice for verification. The laboratory performed additional testing on results that showed discrepancies.

Chemotherapy and dose adjustment

Patients received fluoropyrimidines‑ based chemotherapy regimens according to institutional protocols. For patients found to have DPYD variants, dose reduction was implemented based on CPIC recommendations using DPYD activity score (DPYD‑ AS):

• Activity score 2.0: Normal metabolism, full dose.

• Score 1.5‑1.0: Intermediate metabolism, 25‑50% dose reduction.

• Score ≤ 0.5: Poor metabolism, avoid fluoropyrimidines or use with extreme caution and dose reduction.

Toxicity assessments

Toxicity data were collected from electronic medical records and categorized to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 [7]. The following toxicities were specifically analysed:

• Gastrointestinal toxicity (diarrhoea mucositis)

• Hematologic toxicity (neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anaemia)

• Hand‑foot syndrome

• Overall grade 3‑4 toxicity incidence.

Outcomes

• Primary outcome: Prevalence of clinically relevant DPYD mutations in the study population

• Secondary outcome: Incidence and severity of chemotherapy‑related toxicities in DPYD‑ mutant patients receiving adjusted dose versus wild‑type patients.

Data collection and statistical analysis

All data were retrieved from the institutional electronic medical record system (Arya) [8]. Data included demographic, clinical, treatment, genotyping, and toxicity parameters. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to treatment, and data were anonymized to ensure confidentiality.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.

Univariate Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarised as median (inter‑quartile range, IQR) for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables.

The primary end point was the occurrence of grade ≥ 3 fluoropyrimidine‑related toxicity during the first two cycles. For each prespecified predictor (sex, age, ECOG, tumour stage, chemotherapy regime, DPYD genotype, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease) we performed univariate comparisons with the endpoint.

• Continuous predictors were assessed with a two‑sample t‑test when normally distributed (Shapiro‑Wilk p>0.05) or with the Mann‑Whitney U test otherwise. Effect size was expressed as Cohens d or rank‑biserial correlation, respectively.

• Categorical predictors were compared with the χ² test of independence; Fishers exact test replaced with χ² test if an expected cell count was <5. Effect size was reported as Cramer’s V (small ≥ 0.10, medium ≥ 0.30, large ≥ 0.50). Two‑side p values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Multivariable logistic regression

Variables with biological plausibility and/or univariate p<0.20 were simultaneously entered into binary logistic regression model (ENTER method). The final model included DPYD genotype, age, ECOG performance status, tumour stage, chemotherapy regime and diabetes mellitus. Multicollinearity was assessed with variance inflation factor (VIF<2 for all covariates). Model calibration was evaluated with Hosmer‑Lemeshow goodness‑of‑fir test and discrimination with the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC). Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) is reported with 95% confidence interval (CI).

The study performed two sensitivity analyses by (a) focusing on DPYD 9A carriers and(b) removing homozygous mutant patients to assess the stability of logistic regression results. The analysis maintained the same covariates and model structure.

Results

This study evaluated 66 patients with GI cancer undergoing 5‑FU based chemotherapy at a tertiary care Center in North India. The median age was 56 years (IQR 48‑63); 37/66(56%) were male. The ECOG performance score was 1 in 59/66 (89.7%) of cases. Stage III disease was most common 34/66 (51.7%), followed by stage IV 26/66 (39.9%). All tumours were adenocarcinoma with 56.1% being well‑differentiated. Surgical resection was performed in 27.3% cases. Comorbidities included hypertension (27.6%), diabetes mellitus (10%) and coronary heart disease (2%).

Chemotherapy Chemotherapy was delivered with curative intent in 37/66 (56.1%). FOLFOX was used in 38 (57.6%) of cases, CAPOX in 20 (30.3%) and others in 8 (12.1%) DPYD mutation were present in 48.5 % of patients (heterozygous 43.9%, homozygous 4.5%) and all received genotype‑guided dose adjustments (Table 1).

| Variable | Category | N | % (95% CI) |

| Any DPYD mutation | Present | 32 | 48.5% (36.4‑60.5) |

| Wild‑type | 34 | 51.50% | |

| Specific variants | DPYD 9A (c.85 T>A) | 29 | 43.9% (31.9‑55.9) |

| DPYD 2A (c.2846 A>T) | 3 | 4.5% (0.0‑9.6) | |

| Zygosity | Heterozygous | 29 | 43.90% |

| Homozygous | 3 | 4.50% | |

| Allele frequency+ | - | 35/132 chromosomes | 26.50% |

Includes mutation frequency and zygosity distribution. Allele frequency calculated as mutant alleles / total alleles (n=132).

Wild‑type patients (51.5%) received standard doses.

Toxicity grade distribution

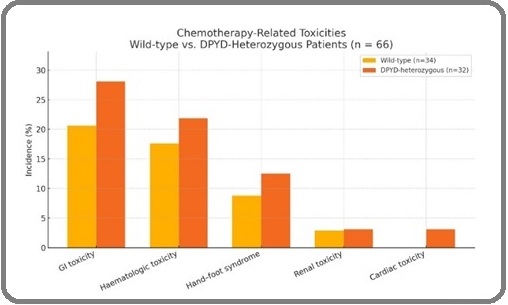

GI toxicity occurred in 21% of wild ‑type patients (7/34) and 28% of mutant patients (9/32). The difference was not statistically significant (p=0.570), indicating comparable GI‑toxicity rates after genotype‑guided adjustment (Table 2).

| Toxicity Type | Wild‑Type (n=34) | Mutant (n=32) | p‑value |

| Gastrointestinal toxicity (Any grade) | 20.6% (7/34) | 28.1% (9/32) | 0.57 |

| Grade 3–4 GI toxicity | 5.9% (2/34) | 3.1% (1/32) | 1 |

| Hematologic toxicity (Any grade) | 17.6% (6/34) | 21.9% (7/32) | 0.762 |

| Grade 3–4 Hematologic | 2.9% (1/34) | 3.1% (1/32) | 1 |

| Hand‑foot syndrome | 8.8% (3/34) | 12.5% (4/32) | 0.705 |

| Renal toxicity | 2.9% (1/34) | 3.1% (1/32) | 1 |

| Cardiac toxicity | 0% (0/34) | 3.1% (1/32) | 0.485 |

Wild‑type vs mutant groups; p‑values based on two‑sided Fisher’s exact test with continuity correction.

Sever events (CTCAE grade ≥ 3) remained infrequent‑5.9 % vs 3.1 % in wild‑type and mutant groups, respectively(p=1.000).

Hematologic adverse events were observed in 18% of wild‑type patients (6/34) and 22% of mutant patients (7/32), again showing no significant difference (p=0.762). This suggests that adjusted dosing in mutant group effectively reduced hematologic toxicity risk. Grade 3‑4 hematologic toxicity was low and virtually identical (2.9% vs 3.1%; p=1.000), underscoring the effectiveness of dose reduction in mitigating risk for carriers.

A slightly higher proportion of patients in mutant group experienced hand‑foot syndrome (12.5%) compared to the wild‑type group (8.8%), but the difference was not significant(p=0.705).

Renal adverse events occurred in 2.9% of wild‑type patients vs 3.1% in mutant patients(p=1.000). Though the rate was slightly higher in mutant group, the result was statistically non‑significant.

Cardiac toxicity was absent in wild‑type arm and observed in one mutant patient (3.1%); the very low event count precluded meaningful statical power (p=0.485) Table1 and Figure 1 shows the comparison of chemotherapy ‑associated toxicities between wild‑type and mutant DPYD groups.

Figure 1. Chemotherapy Toxicities by DPYD Genotype (Wild‑type vs Mutant). Proportion of patients experiencing GI, hematologic, hand‑foot, renal, and cardiac toxicities. No significant differences observed (Fisher’s test).

Univariate Statistical analysis

On univariate testing, diabetes mellitus showed a significant association with grade ≥ 3 toxicity (57% vs 17%; χ²=6.8, p=0.01; Cramer’s V=0.31, medium effect). DPYD mutation status demonstrated a non‑significant 4 ‑percentage‑point increase in toxicity risk (22% vs 18%; Fishers exact p =0.28). None of the remaining demographic or treatment ‑related factors reached statistical significance (all p> 0.30; Table 3A).

| Grade ≥ 3 toxicity n/N | No Grade ≥ 3 toxicity n/N (%) | |||||

| Variable | Category (%) | N (%) | P value | Effect size | ||

| DPYD genotype | Wild type | 6/34 (17.6) | 28/34 (82.4) | 0.28 | V=0.12 | |

| Mutated | 7/32 (21.9) | 25/32 (78.1) | ||||

| Sex | Male | 8/37 (21.6) | 29/37 (78.4) | 0.71 | V=0.05 | |

| Female | 5/29 (17.2) | 24/29 (82.8) | ||||

| Age, y | - | 58 ± 11 | 55 ± 12 | 0.34 | d=0.26 | |

| ECOG PS | 0 | 2/4 (50) | 2/4 (50) | 0.09 | V=0.24 | |

| 1 | 10/59 (17) | 49/59 (85.3) | ||||

| Stage | III | 5/34 (14.7) | 29/34 (85.3) | 0.42 | V=0.10 | |

| IV | 6/26 (23.1) | 20/26 (76.9) | ||||

| Chemo regime | FOLFOX | 9/38 (23.7) | 29/38 (76.3) | 0.66 | V=0.07 | |

| CAPOX | 3/20 (15) | 17/20 (85) | ||||

| Others | 1/8 (12.5) | 7/8 (87.5) | ||||

| Comorbid DM | Yes | 4/7 (57.1) | 3/7 (42.9) | 0.01 | V=0.31 | |

| Comorbid HT | Yes | 3/18 (16.7) | 15/18 (83.3) | 0.84 | V=0.03 |

Cohen's d or Cramer’s V reported as effect size. Bolded p‑values <0.05 are statistically significant. Numbers in bold are the event counts; continuous variables are presented as mean ±SD.

Multivariable Logistic regression

After simultaneous adjustment, diabetic mellitus remained an independent predictor of grade ≥ 3 toxicity (a OR 5.99,95%CI 1.19‑30.3, p‑0.03), whereas DPYD mutation status did not reach significance (a OR 1.2795% CI 0.46‑3.52, p=0.65). This model showed good calibration (Hosmer‑Lemeshow p=0.74) and modest discrimination (AUC 0.67) (Table 3B).

| Predictor | Β (SE) | aOR | 95% CI | p value |

| DPYD Mutation (vs wild type) | 0.24 (0.51) | 1.27 | 0.46‑3.52 | 0.65 |

| Age (per year) | 0.03 (0.02) | 1.03 | 0.99‑1.08 | 0.26 |

| ECOG 1(vs 0) | ‑0.91 (0.83) | 0.4 | 0.08‑1.93 | `0.26 |

| Stage IV (vs III) | 0.48 (0.58) | 1.61 | 0.52‑4.97 | 0.41 |

| Regimen CAPOX (vs FOLFOX) | ‑0.37 (0.75) | 0.69 | 0.15‑3.19 | 0.64 |

| Regime other (vs FOLFOX) | ‑0.86 (1.15) | 0.42 | 0.04‑4.29 | 0.46 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes vs no) | 1.79 (0.83) | 5.99 | 1.19‑30.3 | 0.03 |

Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% CI; Hosmer‑Lemeshow and AUC included for model calibration and discrimination.

This retrospective study confirms the clinical utility of pharmacogenomics profiling in GI cancer patients undergoing fluoropyrimidines‑based chemotherapy. Among 66 consecutively treated patients, 32 (48.5%) harboured a clinically actionable DPYD variant and therefore received genotype‑guided dose reductions in line with CPIC recommendation.

Univariate analysis revealed that diabetes mellitus was only variable significantly associated with grade ≥ 3 toxicity (57% vs 17%; p=0.01; Cramer’s V =0.31, medium effect). Neither DPYD‑mutation status (22% vs 18%; p=0.28) nor age, ECOG performance score, tumour stage or chemotherapy regime showed statically relevant influence.

Multivariable logistic regression (variable entered: DPYD status, age, ECOG, stage, regime, diabetes) confirmed that diabetes mellitus independently increased the odds of high‑ grade toxicity almost six‑fold ( adjusted OR 5.99,95% CI 1.19‑30.3,p=0.03). DPYD‑ mutation status remained non‑significant after adjustment (aOR 1.27,95% CI 0.46‑3.52, p=0.65).The model calibrated well (Hosmer‑Lemeshow p=0.74) and displayed modest discriminative ability (AUC=0.67), indicating that routine clinicopathological variables alone are insufficient for accurate toxicity perdition. The sensitivity analyses confirmed that the obtained results were stable. The multivariable model was re‑run without homozygous DPYD mutants (n=3) and diabetes mellitus remained significantly associated with grade ≥3 toxicity (aOR 5.92; 95% CI 1.13–30.9; p=0.035) while DPYD mutation status remained non‑significant (aOR 1.21; 95% CI 0.43–3.41; p=0.70). The results were similar when the analysis was restricted to only DPYD*9A (c.85T>C) carriers (n=29) (aOR 1.15; 95% CI 0.40–3.33; p=0.78), which confirmed the consistency of outcomes across genotype subsets.

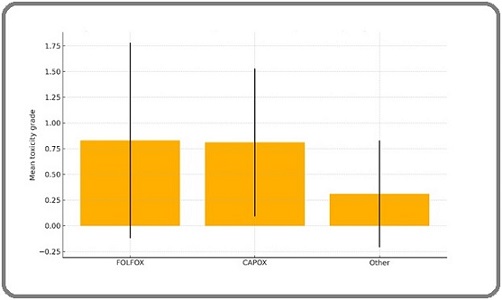

Across treatment regimes, the mean toxicity grade did not differ materially (Table 4, Figure 2).

| Regimen | n | Mean Toxicity Grade± SD |

| FOLFOX | 38 | 0.83 ± 0.72 |

| CAPOX | 20 | 0.81 ± 0.72 |

| Other | 8 | 0.31 ± 0.52 |

Toxicity graded per CTCAE v5.0. Regimen 'Other' includes 5‑FU/leu‑ covorin and MMC‑based protocols.

Figure 2. Mean Chemotherapy‑Induced Toxicity Grade by Regimen. Mean ± SD for FOLFOX, CAPOX, and other regimens. No significant differences observed between groups (ANOVA p > 0.05).

Point estimate illustrates near‑identical averages for FOLFOX and CAPOX, with numerically lower grades in the small “other” group. Standardized good comparability between mutant and wild‑type cohorts.

Taken together, these data validate the current practice of genotype‑guided dose attenuation, which neutralises the excess toxicity risk conferred by DPYD variants without compromising treatment intent. The finding also highlights diabetes mellitus as an easily recognisable clinical factor warranting closer toxicity surveillance, and they underscore the need for additional biomarkers beyond traditional variables to enhance risk stratifications in future predictive models

Discussion

Our research supports worldwide studies which demonstrate that DPYD genotype‑based dosing helps reduce fluoropyrimidine toxicity.

Among 66 gastrointestinal ‑cancer patients,48.5% carried an actionable variant‑predominantly DPYD 9A (c.85 T>C), which accounted for >90% of all mutations detected‑yet the incidence of grade ≥ 3 adverse events did not differ from wild‑type patients once CPIC dose reductions had been applied. These rea‑world outcomes echo the pragmatic JAMA Network Open trial in which prospective DPYD/UGT1A1‑guided prescribing halved severe toxicities without compromising efficacy [9].

Prevalence and regional heterogeneity

The high mutation rate (48.5%) driven largely by 9A exceeds Western and South Indian data, emphasizing regional genomic differences [5, 10], with [5] reporting 12.5% prevalence in South India. Additionally, the role of DPYD variants in Indian chemotherapy toxicity was highlighted by Kaur et al. [10], supporting the value of population‑specific testing panels.

Effectiveness of genotype-guided dosing

The research supports worldwide evidence that DPYD genotype‑guided dose education effectively reduces severe fluoropyrimidine toxicity. The toxicity rates of variant carriers in our cohort matched those of wild‑type patients thus validating the clinical value of CPIC activity‑ score–based dosing algorithms in an Indian context. The study supports the need for standard DPYD testing because North India has a high allele prevalence and NCCN 2024 guidelines now recommend genotype‑informed therapy to enhance treatment safety [11].

Clinical covariates: the diabetes signal

On multivariable analysis, diabetes mellitus emerged as a six‑fold independent predictor of grade ≥ 3 toxicity, corroborating emerging mechanistic data linking hyperglycaemia to heightened oxidative and inflammatory injury during 5‑FU therapy [12]. Proactive metabolic optimisation and intensified toxicity surveillance in diabetic patients‑irrespective of genotype‑therefore appear prudent.

Practice and policy implications

Key takeaway:Practical action

Universal DPYD screening is feasible and cost-saving:

Universal DPYD screening is increasingly considered feasible and potentially cost‑saving based on international real‑world implementation studies [12, 13].

Panel content must reflect Indian genetics: All Indian assays should mandatorily include DPYD 9A to avoid false negative “wild‑type” calls

Digital decision support driven adherence: Embedding DPPYD activity‑score calculators and dose presets into electronic health records sustains guideline‑concordant prescribing [12].

The research results confirm that Indian oncology practice should implement mandatory DPYD testing before patients receive fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. National testing protocols need to include the DPYD*9Aallele because it exists at high frequencies in our population to prevent incorrect negative test results. The discovery of diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for severe toxicity demonstrates the requirement for improved monitoring and metabolic improvement regardless of patient genetic makeup. The implementation of genotype‑based dosing algorithms integrated into electronic health records (EHRs) will enable timely guideline‑compliant prescribing. These measures will establish a safer precision‑guided fluoropyrimidine therapy system throughout various Indian healthcare settings.

Limitations and future directions

The research contains multiple crucial restrictions. The study’s single‑centre retrospective design makes it vulnerable to referral and documentation bias which reduces its ability to be generalized. The research needs to include prospective cohorts from multiple institutions and population‑based studies to improve external validity. The study used only four common DPYD variants in its mutation panel which might have excluded rare mutations that could be clinically important. The risk stratification process would become more complete by using expanded genotyping panels together with next‑generation sequencing and functional DPD enzyme assays. The small study size restricted researchers from performing adequate subgroup analyses especially when studying patients with homozygous variants and different chemotherapy types. The robustness of multivariable findings was confirmed through sensitivity analyses which demonstrated that results remained consistent across different subgroups and after removing outlier genotypes. The study’s inability to measure pharmacokinetic data and efficacy endpoints such as response rate and survival prevents complete assessment of clinical benefits. Future research must track patients over time while expanding genetic variant testing and performing cost‑effectiveness assessments to develop personalized chemotherapy dosing recommendations for Indian oncology practice.

Next‑ generation studies should integrate pharmacokinetics, inflammatory biomarkers, and machine‑ learning risk models to refine personalised dosing beyond the current binary genotype farmwork. The robustness of multivariable findings was confirmed through sensitivity analyses which demonstrated that results remained consistent across different subgroups and after removing outlier genotypes.

Together with growing international evidence on safety and the potential for cost‑effectiveness and seamless electronic‑health‑record integration of genotype‑guided dosing [9, 12], our findings support:

1. Mandatory DPYD testing before fluoropyrimidine therapy across Indian Oncology services, with assured laboratory turn‑around <72 h;

2. Inclusion of DPYD 9A in all Indian testing panels;

3. Parallel optimisation of modifiable risk, particularly diabetes.

By aligning pharmacogenomic with regional allele prevalence and conventional clinical risk factors, Indian oncology can deliver genuinely precision‑based, safe fluoropyrimidines therapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Department of Genetic laboratory, Dayanand Medical College & Hospital, for technical support with DPYD genotyping.

Statements and Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no financial or non‑financial conflicts of interest related to content of this article.

Ethics Approval

Under institutional policy and the Indian Council of Medical Research National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research Involving Human Participants (2017), retrospective studies that analyse fully anonymised routine‑care data are exempt from formal Institutional Ethics Committee review. Accordingly, this study did not seek separate Ethics approval.

Informed Consent to participate

Because the analysis used de‑identified data obtained during standard‑of‑care treatment and posed no additional risk to patients, individual informed consent was not required under then above guidelines.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable. This article contains only aggregate, de‑identified data and no images or information that could identify individual participants.

Data Availability

De‑identified datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Patient‑level genetic data cannot be released publicly to protect participant privacy.

Code availability

Not applicable‑no custom code or algorithms were generated.

Author Contributions

Dr Manjinder singh sidhu (corresponding author) conceived and designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and revised it critically for important intellectual content. Dr Barjinder Kaur curated the clinical and genotyping data. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. No identifiable personal data, images, or clinical information of individual patients are presented in this manuscript.

Declaration on generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Portions of this manuscript (including language refinement, formatting adjustments, and reference structuring) were assisted by generative AI tools. All content was carefully reviewed, verified, and approved by the authors. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the scientific content.

References

- Admission Pattern of Gastrointestinal Cancer for 2020-2023 From a Single Tertiary-Care Hospital in Pune, Western Maharashtra Thombare M, Jillawar N, Gandhi V, Kulkarni A, Vane A, Joshi V, Deshmukh M. Cureus.2024;16(8). CrossRef

- Impact of pharmacogenomic DPYD variant guided dosing on toxicity in patients receiving fluoropyrimidines for gastrointestinal cancers in a high-volume tertiary centre Lau DK , Fong C, Arouri F, Cortez L, Katifi H, Gonzalez-Exposito R, Razzaq MB , et al . BMC cancer.2023;23(1). CrossRef

- Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update Amstutz U, Henricks LM , Offer SM , Barbarino J, Schellens JHM , Swen JJ , Klein TE , et al . Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics.2018;103(2). CrossRef

- Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency in patients treated with 5FU or capecitabine based regimens: A single center experience from South India. Pavithran K, Ariyannur P, Jayamohanan H, Philip A, Jose WM , Soman S. Journal of Clinical Oncology.2021;39(15_suppl). CrossRef

- Pharmacogenetic profiling of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD) variants in the Indian population Naushad SM , Hussain T, Alrokayan SA , Kutala VK . The Journal of Gene Medicine.2021;23(1). CrossRef

- National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0—Quick Reference (5 × 7 inch). https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2025 2017.

- AryaEHR .Arya electronic health-record platform. https://www.aryaehr.com/. Accessed 11 May 2025 2025.

- Clinical Benefits and Utility of Pretherapeutic DPYD and UGT1A1 Testing in Gastrointestinal Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of the PREPARE Randomized Clinical Trial Roncato R, Bignucolo A, Peruzzi E, Montico M, De Mattia E, Foltran L, Guardascione M, et al . JAMA network open.2024;7(12). CrossRef

- The Prevalence of DPYD*9A(c.85T>C) Genotype and the Genotype-Phenotype Correlation in Patients with Gastrointestinal Malignancies Treated With Fluoropyrimidines: Updated Analysis Maharjan AS , McMillin GA , Patel GK , Awan S, Taylor WR , Pai S, Frankel AE , et al . Clinical Colorectal Cancer.2019;18(3). CrossRef

- Genetic polymorphisms and chemotherapy toxicity in gastrointestinal cancers: an Indian perspective Kaur G, Aggarwal N, Gupta S, Sharma A, Verma R, Kapoor R. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.2022;23(5):1567–1574.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2025) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer, Version 3.2025 https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?id=1428. Accessed 11 May 2025..

- Cost-effectiveness of DPYD Genotyping Prior to Fluoropyrimidine-based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer Brooks GA , Tapp S, Daly AT , Busam JA , Tosteson ANA . Clinical Colorectal Cancer.2022;21(3). CrossRef

- Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Deficiency (DPYD) Genotyping-Guided Fluoropyrimidine-Based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer. A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Abushanab D, Mohamed S, Abdel-Latif R, Moustafa DA , Marridi W, Elazzazy S, Badji R, et al . Clinical Drug Investigation.2025;45(3). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2025

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times