Epidemiological Profile of Breast Cancer Phenotypes in Rural Southern West Bengal, India

Download

Abstract

Background: Breast cancer (BC) is now the most common cancer globally, exceeding lung cancer in 2020 with 2.3 million new cases. In 2016, India had an estimated 118,000 new cases, with a 39.1% increase in the age-standardized incidence rate between 1990 and 2016. This abstract highlights the growing global burden of BC, particularly focusing on the increasing incidence in rural India.

Methods: A retrospective, observational study was conducted at the Department of Radiation Oncology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani, focusing on rural areas in southern West Bengal between July 2022 and January 2025 in women with biopsy-proven breast cancer. The data of the patients pertaining to histopathology, hormone status, Grade of tumour, Ki-67 Index, and demography were collected, and phenotypical classification was derived.

Results: Among 456 breast cancer patients (159 premenopausal, 297 postmenopausal), 58.1% had locally advanced disease. Most presented with grade III tumours (51.8%) and high Ki-67 (67.9%). Infiltrating ductal carcinoma was predominant. Hormone receptor positivity was higher in premenopausal (64.77%) vs postmenopausal (52.52%) women; HER2 neu negative cases were more common in postmenopausal women (67.33%). Predominant phenotypic subgroups: premenopausal luminal B (40.9%), postmenopausal luminal A (34%).

Interpretation and Conclusion: The findings suggest the need for tailored therapeutic strategies, especially considering the distinct phenotypic subgroups identified. Overall, these insights contribute to a better understanding of breast cancer’s epidemiology and may inform future treatment approaches and research directions in this area.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common malignancy among women worldwide, exceeding lung cancer in 2020, with 2.3 million newly diagnosed cases, accounting for 11.7% of all cancer cases. The overall cancer incidence was observed to be two to three times higher in developed countries compared to developing countries for both men and women. However, mortality rates showed less than a twofold difference among men and minimal variation among women. Mortality rates for female breast and cervical cancers, however, were considerably higher in developing countries versus developed countries (15.0 vs 12.8 per 100,000 and 12.4 vs 5.2 per 100,000, respectively) [1]. As per epidemiological studies, the global burden of BC is expected to surpass 2 million by 2030 [2].

Between 1965 and 1985, the breast cancer incidence in India increased significantly, nearly doubling during this period. In 2016, the number of new cases was 118,000 (95% uncertainty interval: 107,000 to 130,000), with 98.1% occurring in females [3]. Additionally, the number of prevalent cases was estimated at 526,000 (95% uncertainty interval: 474,000 to 574,000). Over the 26 years from 1990 to 2016, the age-standardized incidence rate of breast cancer in females increased by 39.1% (95% uncertainty interval: 5.1% to 85.5%) across India, with this rise observed consistently in every state of the country [4].

Recent trends indicate that breast cancer is increasingly affecting younger women in India in comparison to Western countries. The National Cancer Registry Program analysed data from cancer registries spanning 1988 to 2013 to evaluate changes in cancer incidence. Findings revealed a significant rise in breast cancer cases across all population-based cancer registries in India [5]. There is also a lack of knowledge of breast carcinoma and the importance of its screening tools in the rural population [6].

A study on breast cancer survival rates revealed that the 5-year overall survival varies significantly by stage. For patients diagnosed at stage I, the survival rate is 95%, decreasing to 92% for stage II, 70% for stage III, and only 21% for stage IV [7]. The survival rate for breast cancer patients in India is significantly lower compared to Western countries. This disparity is attributed to factors such as an earlier age of onset, advanced disease stage at diagnosis, delays in initiating definitive treatment, and fragmented or inadequate care [8]. According to the World Cancer Report 2020, the most effective strategy for controlling breast cancer involves early detection and prompt treatment [9]. A systematic review conducted in 2018, which analysed data from 20 studies, found that the cost of breast cancer treatment increases significantly with advanced stages at diagnosis. The study highlighted that earlier detection of breast cancer can help reduce treatment costs, as managing early-stage disease is less resource-intensive compared to later stages [10]. Early identification of phenotypic subtypes and proper categorization of breast cancer patients are essential steps in devising an effective treatment plan with curative intent [11, 12].

The data for phenotypic classification of Breast cancer patients is dismal for the Indian rural population, owing to limited access to proper cancer care facilities or lack of financial support. Moreover, the lack of proper awareness and social taboos associated with breast cancer often results in most patients taking medical advice only when the disease reaches advanced stages, which is another problem when it comes to the rural population of India.

Objectives

-To find out the epidemiological distribution of different phenotypic subgroups in the patients suffering from Carcinoma of Breast, registered in the hospital-based cancer Registry of the OPD of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani, West Bengal, India, which predominantly caters to the rural population of the Southern districts of West Bengal.

-To find out any difference in disease biology and its epidemiologic distribution in our rural population, compared to the international data.

Materials and Methods

Patients

After approval from the Institutional Research Committee, the data of all patients with HPE-proven Breast cancer from July 2022 to January 2025 were obtained from the hospital-based Cancer Registry of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani, tabulated, and analyzed. Data from pre-operative and post-operative cases having their Estrogen Receptor (ER)/ Progesterone Receptor (PR)/HER2 neu Receptor /Ki-67 reports were taken for the study. Patients who did not have these reports done or who had incomplete/ inconclusive reports were not considered for the study.

A total of 706 new patients with HPE-proven breast cancer attended the OPD section of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani, between July 2022 and January 2025. Among 706 patients, the data for the phenotypic varieties consisting of ER/PR/HER2 neu receptor and Ki-67 status were available only for 456 patients (64.6%).

Evaluation

The ER/PR/HER2 neu receptor and Ki-67 status of the patients were evaluated from their pre- and post-operative HPE slides, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed at the AIIMS Pathology laboratory according to standard guidelines.

Reporting Results of Estrogen Receptor and Progesterone Receptor Testing as per 2010 ASCO guidelines [13] (See Table 1).

| Result | Criteria | Comments |

| Positive | Immunoreactive tumor cells present (>/=1%) | The percentage of immunoreactive cells may be determined by visual estimation or quantitation. Quantitation can be provided by reporting the percentage of positive cells or by a scoring system, such as the Allred or H scores. |

| Negative | <1% immunoreactive tumor cells present |

Recommendations for HER2 neu Testing in Breast Cancer: ASCO/CAP Guideline 2013 [14] (See Table 2).

| Must report HER2 neu test result as positive for HER2 neu if | · IHC 3+ based on circumferential membrane staining that is complete and intense |

| · ISH positive based on: | |

| - Single-probe average HER2 neucopy number ≥ 6.0 signals/cell | |

| - Dual-probe HER2 neu /CEP17 ratio ≥ 2.0 with an average HER2 copy number ≥ 4.0 signals per cell | |

| - Dual-probe HER2 neu 2/CEP17 ratio ≥ 2.0 with an average HER2 neucopy number < 4.0 signals/cell | |

| - Dual-probe HER2 neu /CEP17 ratio < 2.0 with an average HER2 neucopy number ≥ 6.0 signals/cell | |

| Must report HER2 neu test result as equivocal and order reflex test (same specimen using the alternative test) or new test (new specimen, if available, using same or alternative test) if | · IHC 2+ based on circumferential membrane staining that is incomplete and/or weak/moderate and within > 10% of the invasive tumor cells or complete and circumferential membrane staining that is intense and within ≤ 10% of the invasive tumor cells |

| · ISH equivocal based on: Single-probe ISH average HER2 neu copy number ≥ 4.0 and < 6.0 signals/cell | |

| Must report HER2 neu test result as negative if a single test (or both tests) is performed, and shows | · IHC 1+ as defined by incomplete membrane staining that is faint/barely perceptible and within > 10% of the invasive tumor cells |

| · IHC 0 as defined by no staining observed or membrane staining that is incomplete and is faint/barely perceptible and within ≤ 10% of the invasive tumor cells | |

| · ISH negative based on: | |

| - Single-probe average HER2 neu copy number < 4.0 signals/ cell | |

| - Dual-probe HER2 neu /CEP17 ratio < 2.0 with an average HER2 neu copy number < 4.0 signals/cell |

The data of 456 patients were tabulated in an IBM SPSS Statistics data editor worksheet, analysed, and evaluated. Each patient was assigned a phenotypic subgroup according to the Gallen consensus 2013 [15].

Results

Out of 456 registered patients (Table 3), the majority of the patients were diagnosed with infiltrating ductal variety of carcinoma of the breast (433 patients: 95%, p value = 0.00), 15 patients (3.3%) had lobular carcinoma, and 8 patients (1.8%) had mucinous carcinoma. The median age of the patients was 50 years (Range 25-86 years).

| N = 456 | ||

| Menopausal Status | ||

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Post | 297 | 65.1 |

| Pre | 159 | 34.9 |

| T otal | 456 | 100 |

| HPE Subtype | ||

| IDC | 433 | 95 |

| Lobular | 15 | 3.3 |

| Mucinous | 8 | 1.8 |

| Total | 456 | 100 |

| Stage At Presentation | ||

| EBC | 81 | 17.8 |

| LABC | 265 | 58.1 |

| Metastatic (S) | 51 | 11.2 |

| Metastatic (V) | 59 | 12.9 |

| Total | 456 | 100 |

| Grade | ||

| I | 54 | 11.8 |

| II | 166 | 36.4 |

| III | 236 | 51.8 |

| Total | 456 | 100 |

| Phenotype | ||

| HER2 neu overexpressing | 66 | 14.5 |

| Luminal A | 147 | 32.2 |

| Luminal B | 134 | 29.4 |

| TNBC | 109 | 23.9 |

| Total | 456 | 100 |

159 patients (34.9%) belonged to the premenopausal age group, whereas 297 (65.1%) belonged to the postmenopausal age group. The majority of the patients had presented with locally advanced breast cancer (265 patients – 58.1%), followed by early breast cancer (81 patients – 17.8%), visceral metastasis (59 patients -12.9%), and skeletal only metastasis (51 patients – 11.2%), being the least common stage of presentation. 236 patients (51.8%) presented with Grade III disease, 166 patients (36.4%) presented with Grade II disease, whereas 54 patients (11.8%) presented with Grade I disease.

Premenopausal subgroup

The median age of presentation of patients in the premenopausal subgroup was 39 years (Range: 25- 48 years). 142 patients (89.3%) were diagnosed with infiltrating ductal carcinoma, 9 patients (5.7%) were diagnosed with lobular carcinoma, whereas 8 patients (5%) were diagnosed with mucinous carcinoma. 81 patients (50.9%) presented with Grade III disease, 58 patients (36.5%) presented with Grade II disease, whereas 20 patients (12.6%) presented with Grade I disease. 98 patients (61.6%) presented in the locally advanced stage, and 33 patients (20.8%) presented in the early breast cancer stage.

16 patients (10.1%) presented with skeletal-only metastasis, whereas the other 12 patients (7.5%) presented with visceral metastasis.

Postmenopausal subgroup

The median age of presentation of patients in the postmenopausal subgroup was 56 years (Range: 42-86 years). 291 patients (98%) were diagnosed with infiltrating ductal carcinoma, whereas 6 patients (2%) were diagnosed with lobular carcinoma. 155 patients (52.2%) presented with Grade III disease, 108 patients (36.4%) presented with Grade II disease, whereas 34 patients (11.4%) presented with Grade I disease. 167 patients (56.2%) presented in the locally advanced stage, 48 patients (16.2%) presented in the early breast cancer stage, 35 patients (11.8%) presented with skeletal only metastasis, whereas the other 47 patients (15.8%) presented with visceral metastasis.

Discussion

Western studies [16-18] report the incidence of Invasive Breast Cancer as 40-80% [19]; and approximately 25% of invasive breast cancers exhibit distinct growth patterns and cytological characteristics, allowing them to be classified into specific subtypes (Table 4).

| Intrinsic subtype | Clinico-pathologic surrogate definition | Notes |

| Luminal A | ‘Luminal A-like’ all of: § ER and PR positive § HER2 negative § Ki-67 ‘low’ § Recurrence risk ‘low’ based on multi-gene-expression assay (if available) | The cut-point between ‘high’ and ‘low’ values for Ki-67 varies between laboratories. A level of <14% best correlated with the gene-expression definition of Luminal A based on the results in a single reference laboratory. Similarly, the added value of PR in distinguishing between ‘Luminal A-like’ and ‘Luminal B-like’ subtypes derives from the work of Prat et al., which used a PR cut-point of ≥20% to best correspond to the Luminal A subtype. Quality assurance programmes are essential for laboratories reporting these results. |

| Luminal B | ‘Luminal B-like (HER2 neu negative)’ § ER positive § HER2 negative and at least one of: § Ki-67 ‘high’ § PR negative or 'low' § Recurrence risk ‘high’ based on multi-gene-expression assay (if available) ‘Luminal B-like (HER2 neu positive)’ § ER positive § HER2 overexpressed or amplified § Any Ki-67 § Any PR | ‘Luminal B-like’ disease comprises those luminal cases that lack the characteristics noted above for ‘Luminal A-like’ disease. Thus, either a high Ki-67 value or a low PR value (see above) may be used to distinguish between ‘Luminal A-like’ and ‘Luminal B-like (HER2 neu negative)’. |

| HER2 neu overexpression | ‘HER2 neu positive (non-luminal)’ § HER2 neu overexpressed or amplified § ER and PR are absent | |

| ‘Basal-like’ | ‘Triple negative (ductal)’ § ER and PR are absent § HER2 neu negative | There is an 80% overlap between the 'triple-negative' and the intrinsic 'basal-like' subtype. Some cases with low-positive ER staining may cluster with non-luminal subtypes on gene-expression analysis. 'Triple negative' also includes a few special histological types, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma. |

These include invasive lobular carcinoma, tubular carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma (types A and B), and neuroendocrine carcinoma [20]. Luminal breast cancers, which are estrogen receptor-positive (ER-positive) tumours, account for approximately 70% of all breast cancer cases in Western populations [17], whereas the HER2-enriched cancers account for 10–15% of breast cancers [18]. The TNBC group, with an incidence of 13 per 100,000 females, comprises about 10-20% of breast cancer patients in the US [21]. Similar results have also been obtained from Indian studies. The results of this study are comparable with the data obtained from Western studies and previous Indian studies [21-23]. Although the prevalence of Luminal B subtype is slightly higher in this study, possibly because of the revised classification of the molecular subtypes, including the Ki-67 values.

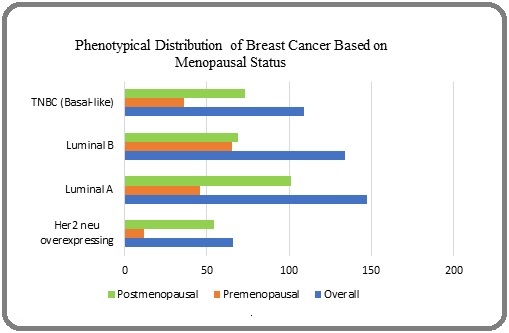

In our study, the Luminal A phenotype is the most prevalent, comprising 32.2% of the total (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Phenotypical Distribution of Breast Cancer Based on Menopausal Status.

The HER2 neu overexpressing group accounts for 14.5%, with specific subcategories showing 13.6% for IHC 3+ and 0.9 % for IHC 2+, ISH positive. The Luminal B phenotype, which includes both HER2 neu negative and positive cases, totals 29.4 %, with detailed percentages of 21.9 % for HER2 neu positive (IHC 3+) and 7.4 % for HER2 neu negative (IHC 2+, ISH positive). Finally, the TNBC (Basal-like) phenotype represents 23.9 % of the cases.

The comparison of breast cancer phenotypes between premenopausal and postmenopausal women reveals significant differences in the distribution and prevalence of various molecular subtypes, which can have implications for treatment and prognosis.

Premenopausal Women

In a cohort of 159 premenopausal women, the Luminal B phenotype was the most common type, accounting for 40.9% (95% CI= 0.33-0.49) of cases, with the majority of instances classified as HER2-neu positive (IHC 3+). This suggests a notable prevalence of aggressive tumour characteristics in this group. The Luminal A subtype comprised 28.9 % (95% CI: 0.22-0.37), which is relatively lower compared to Luminal B. The TNBC (Basal-like) phenotype followed closely, representing 22.6 % (95% CI= 0.16-0.30) of the cases, indicating a higher burden of this aggressive subtype among younger women. The HER2 neu overexpressing phenotype was present in 7.55% (95% CI=0.04-0.12) of the cases. Notably, the increased prevalence of HER2-neu positivity within the Luminal B category highlights a potential trend towards more aggressive disease presentations in premenopausal women.

Postmenopausal Women

In contrast, the data for 297 postmenopausal women (Table 5), showed that the Luminal A phenotype was the most prevalent, accounting for 34 % of cases (95% CI= 0.28-0.39).

| Phenotypes | Subtypes | Overall Frequency (%) | Premenopausal Frequency (%) | Postmenopausal Frequency (%) |

| HER2 neu overexpressing | ER/ PR -ve, | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.3) |

| IHC 2+, ISH +ve | ||||

| ER/ PR -ve, | 62 (13.6) | 12 (7.5) | 50 (16.8) | |

| IHC 3+ | ||||

| Total | 66 (14.5) | 12 (7.5) | 54 (18.2) | |

| Luminal A | ER +ve, PR +ve, Her2 neu -ve, Ki-67 low | 147 (32.2) | 46 (28.9) | 101 (34) |

| Luminal B | ER+, Her2 neu –ve | 34 (7.4) | 8 (5) | 26 (8.7) |

| ER + ve, | 18 (3.9) | 8 (5) | 10 (3.3) | |

| Her2 neu +ve: IHC 2+, ISH +ve | ||||

| Her2 neu +ve: IHC 3+ | 82 (18) | 49 (30.8) | 33 (11.1) | |

| Total | 134 (29.4) | 65 (40.9) | 69 (23.2) | |

| TNBC (Basal-like) | ER/PR/HER2 neu -ve | 109 (23.9) | 36 (22.6) | 73 (24.6) |

| TOTAL | 456 (100) | 159 (100) | 297 (100) |

This indicates a shift towards less aggressive tumour biology in postmenopausal women compared to their premenopausal counterparts. The HER2-neu overexpressing group comprised 18.2% (95% CI = 0.14-0.23), with specific subcategories showing a higher prevalence of IHC 3+ cases (16.8%) compared to IHC 2+, ISH positive cases (1.3%). The Luminal B phenotype represented 23.2 % (95% CI= 0.18-0.28), with both Her 2-neu negative (8.7%) and Her 2-neu positive (14.4%) cases present, suggesting a more diverse tumour biology in this group. Additionally, the TNBC (Basal-like) subtype accounted for 24.6% (95% CI= 0.20-0.30), which is comparable to its prevalence in premenopausal women.

After statistical analysis using the Chi-Square test, there is no statistically significant difference in Luminal A phenotype distribution between pre- and post-menopausal women (p value =0.27).

The contrasting distributions highlight key differences in breast cancer phenotypes between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. In premenopausal women, Luminal B is more prevalent, indicating a tendency towards more aggressive forms of breast cancer [24]. The Luminal A variety predominates in postmenopausal women, suggesting a shift towards less aggressive tumour types [25]. The higher prevalence of TNBC in both groups may correlate with poorer prognostic outcomes due to its aggressive nature and lack of targeted therapies. The predominance of Luminal A in postmenopausal women is associated with better prognosis and responsiveness to hormone therapy.

However, the prevalence of molecular subtypes did not differ much with menopausal status. It was found that the Luminal B subgroup, which is the more aggressive variety, is more common in the premenopausal age group, consistent with previous studies [26]. There is also a link between cancer and negative beliefs rooted in sociocultural backgrounds, which contributes to late diagnosis and management, influencing the survival among the rural population [27]. The distinct phenotypes of breast cancer can significantly impact treatment strategies and clinical outcomes, necessitating their careful consideration in patient management [28, 29].

In conclusion, the findings of our study underscore the importance of considering menopausal status when evaluating breast cancer phenotypes, as they can significantly influence treatment strategies and prognostic outcomes. The higher prevalence of aggressive subtypes like Luminal B and TNBC in premenopausal women necessitates tailored therapeutic approaches to address their unique challenges. In contrast, the predominance of Luminal A in postmenopausal women suggests a potential for more favourable treatment responses. Understanding these phenotypic distributions can inform clinical practice and enhance personalized treatment strategies for breast cancer patients across different age groups and hormonal backgrounds.

Limitations of the study

The study is retrospective and is collected from a single hospital-based cancer registry, which might not be a true representation of the population at large. Out of 706 registered patients, the phenotypical data of 250 patients were not available, which may have influenced the final distribution of the data, leading to a sensitivity bias in this study.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for- profit sectors.

Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Declaration

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani.

References

- Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL , Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2021;71(3). CrossRef

- Breast cancer statistics, 2011 DeSantis C, Siegel R, Bandi P, Jemal A. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2011;61(6). CrossRef

- BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Indian breast cancer patients Saxena S, Szabo CI, Chopin S, Barjhoux L, Sinilnikova O, Lenoir G, Goldgar DE , Bhatanager D. Human Mutation.2002;20(6). CrossRef

- The burden of cancers and their variations across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2016 India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Cancer Collaborators . The Lancet. Oncology.2018;19(10). CrossRef

- National Cancer Registry Programme. Three-year report of population-based cancer registries 2012-2014. Bangalore: Indian Council of Medical Research 2016.

- Breast Cancer Awareness and Associated Factors among Women in Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Study Shoukat Z, Shah AJ . Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2023;24(5). CrossRef

- 327P - Survival Analysis of Breast Cancer Patients Treated at a Tertiary Care Centre in Southern India Arumugham R., Raj A., Nagarajan M., Vijilakshmi R.. Annals of Oncology.2014;25. CrossRef

- Current status of breast cancer management in India Maurya AP , Brahmachari S. Indian J Surg.2021;83(Suppl 2):316-321.

- World cancer report: cancer research for cancer prevention. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. Available from: https://publications.iarc.fr/Non-Series-Publications/World-Cancer-Reports/World-Cancer-Report-Cancer-Research-For-Cancer-Prevention-2020 Wild CP , Weiderpass E, Stewart BW , editors . .

- Global treatment costs of breast cancer by stage: A systematic review Sun L, Legood R, Dos-Santos-Silva I, Gaiha SM , Sadique Z. PloS One.2018;13(11). CrossRef

- Immunohistochemical and clinical characterization of the basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma Nielsen TO , Hsu FO , Jensen K, Cheang M, Karaca G, Hu Z, Hernandez-Boussard T, et al . Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.2004;10(16). CrossRef

- Molecular portraits of human breast tumours Perou C. M., Sørlie T., Eisen M. B., Rijn M., Jeffrey S. S., Rees C. A., Pollack J. R., et al . Nature.2000;406(6797). CrossRef

- Allred score for estrogen and progesterone receptor evaluation. MedicalCriteria.com. [cited 2023 Sep 4] Available from: https://medicalcriteria.com/web/allred/..

- Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update Wolff AC , Hammond MEH , Hicks DG , Dowsett M, McShane LM , Allison KH , et al . J Clin Oncol.2013;31(31):3997-4013.

- Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013 Goldhirsch A., Winer E. P., Coates A. S., Gelber R. D., Piccart-Gebhart M., Thürlimann B., Senn H.-J.. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology.2013;24(9). CrossRef

- Epidemiology of breast cancer subtypes in two prospective cohort studies of breast cancer survivors Kwan ML , Kushi LH , Weltzien E, Maring B, Kutner SE , Fulton RS , Lee MM , Ambrosone CB , Caan BJ . Breast cancer research: BCR.2009;11(3). CrossRef

- US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status Howlader N, Altekruse SF , Li CI , Chen VW , Clarke CA , Ries LAG , Cronin KA . Journal of the National Cancer Institute.2014;106(5). CrossRef

- Breast Cancer-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies-An Updated Review Łukasiewicz S, Czeczelewski M, Forma A, Baj J, Sitarz R, Stanisławek A. Cancers.2021;13(17). CrossRef

- Refinement of breast cancer classification by molecular characterization of histological special types Weigelt B., Horlings H. M., Kreike B., Hayes M. M., Hauptmann M., Wessels L. F. A., Jong D., et al . The Journal of Pathology.2008;216(2). CrossRef

- Histology of Luminal Breast Cancer Erber R, Hartmann A. Breast Care (Basel, Switzerland).2020;15(4). CrossRef

- Triple-negative breast cancer: facts and stats. Medical News Today. 2022. [cited 2023 Jun 1] Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/facts-stats-triple-negative-breast-cancer..

- Prevalence of Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer: A Single Institutional Experience of 2062 Patients Pandit P, Patil R, Palwe V, Gandhe S, Patil R, Nagarkar R. European Journal of Breast Health.2020;16(1). CrossRef

- Prevalence of Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer in India: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Jonnada PK , Sushma C, Karyampudi M, Dharanikota A. Indian Journal of Surgical Oncology.2021;12(Suppl 1). CrossRef

- Ki67 index, HER2 status, and prognosis of patients with luminal B breast cancer Cheang MCU , Chia SK , Voduc D, Gao D, Leung S, Snider J, Watson M, et al . Journal of the National Cancer Institute.2009;101(10). CrossRef

- Prognostic significance of progesterone receptor-positive tumor cells within immunohistochemically defined luminal A breast cancer Prat A, Cheang MCU , Martín M, Parker JS , Carrasco E, Caballero R, Tyldesley S, et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.2013;31(2). CrossRef

- Molecular breast cancer subtypes in premenopausal and postmenopausal African-American women: age-specific prevalence and survival Ihemelandu CU , Leffall LD , Dewitty RL , Naab TJ , Mezghebe HM , Makambi KH , Adams-Campbell , Frederick WA . The Journal of Surgical Research.2007;143(1). CrossRef

- Breast Cancer Myths, Mysterious Miracles and Mistrust among Rural Womenfolk in Sarawak Lim MSH , Mohamad FS , Chew KS , Mat Ali N, Augustin Y. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.2025;26(3). CrossRef

- Outcome of hypofractionated breast irradiation and intraoperative electron boost in early breast cancer: A randomized non‐inferiority clinical trial Fadavi P, Nafissi N, Mahdavi SR , Jafarnejadi B, Javadinia SA . Cancer Reports.2021;4(5). CrossRef

- Clinical Efficacy and Side Effects of IORT as Tumor Bed Boost During Breast-Conserving Surgery in Breast Cancer Patients Following Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Homaei Shandiz F, Fanipakdel A, Forghani MN , Javadinia SA , Mousapour Shahi E, Keramati A, Fazilat-Panah D, Babaei MM . Indian Journal of Gynecologic Oncology.2020;18(2). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2025

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times