Immune Thrombocytopenia as the Initial Presentation of Metastatic High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: A Case Report

Download

Abstract

Introduction: Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an immune-mediated multifactorial disorder characterized by isolated thrombocytopenia which is divided in primary (without an underlying known cause) and secondary (that an underlying cause can be detected). Secondary ITP can be a type of paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS) that occurs in setting of a malignancy.

Case Presentation: Here, we describe a 63-year-old female with newly diagnosed ITP and chief complaint of lower limb ecchymosis which further workups revealed a metastatic highgrade papillary serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) and also after treatment, clinical and laboratory parameters (CA-125) indicated a successful therapeutic response.

Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of evaluating secondary causes, including underlying malignancies, in patients with newly diagnosed ITP, particularly in older individuals. Recognition of ITP as a potential paraneoplastic manifestation may facilitate earlier cancer detection and appropriate management, ultimately improving clinical outcomes.

Introduction

ITP is an immune-mediated multifactorial disorder characterized by isolated thrombocytopenia (platelet (PLT) count < 100 x 109/L) which caused by increased PLT destruction due to B and T cell malfunction. Subsequently, number of megakaryocytes in bone marrow is increased, while it can be normal [1-3].

ITP is divided in primary (without an underlying known cause) and secondary (that an underlying cause such as any diseases or medicine can be detected) [3]. Secondary ITP can be a type of paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS) (occurs in setting of a malignancy) [4] which had higher rate in lymphoma than solid tumors. Here, we present a 63-year-old female with newly diagnosed ITP which further workups revealed a metastatic HGSOC.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old female with a past medical history of diabetes mellitus presented with lower limb ecchymosis to our department. On presentation, her hemodynamics were stable and except for a recent history of weakness and loss of appetite, there was no other complaints. Physical examination revealed unilateral ecchymosis on the right femur (3.5 x 4 cm). The complete blood count (CBC) showed a PLT number 5 x 103/µL (Laboratory results at admission shown in Table 1).

| Parameters | First day of admission | 2 nd day of admission | 3 rd day of admission | 4 th day of admission | 5 th day of admission | 6 th day of admission | Unit | Reference value | |

| WBC | 7.2 | 6.8 | 12.4 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 10 3 /µL | 4-11 | |

| RBC | 4.16 | 3.46 | 3.47 | 3.37 | 3.35 | 3.92 | 10 6 /µL | 4.5 - 5 | |

| Hb | 12 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 10.8 | g/dL | 12.3 - 15.3 | |

| Hct | 36.7 | 30.8 | 32.2 | 32.3 | 30.9 | 36 | % | 36 - 45 | |

| MCV | 88.22 | 89 | 92.8 | 95.85 | 92.24 | 91.84 | fL | 80 - 96 | |

| MCH | 28.85 | 29.8 | 27.67 | 28.19 | 28.06 | 27.55 | pg | 26.5 - 32.5 | |

| MCHC | 32.7 | 33.4 | 29.81 | 29.41 | 30.42 | 30 | g/dL | 33 - 36 | |

| RDW | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 12.3 | 12.7 | 12.5 | % | 11.5 - 15 | |

| PLT | 5 | 19 | 56 | 92 | 131 | 193 | 10 3 /µL | 150 - 450 | |

| diff | Neutrophil | 71.8 | 80.5 | 86 | 85 | 84 | 88 | % | 45.5 - 73.1 |

| Lymphocyte | 21.3 | 17.1 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 10 | % | 20 - 45 | |

| INR | 1.27 | - | - | 1.12 | - | - | - | 0.8 - 1.2 | |

| Creatinine | 1 | - | - | 1.2 | - | - | - | 0.6 - 1.3 |

WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RDW, red blood cell distribution width; PLT, platelet; INR, International normalized ratio

There was no relevant medication history associated with thrombocytopenia. The patient had no prior history of autoimmune diseases, malignancies, recent infections, blood transfusion, vaccination, or use of medications other than oral hypoglycemics for diabetes. Family history was negative for ovarian, breast, or other hereditary cancers. She also had no history of tobacco, alcohol, or drug abuse. After excluding other causes, ITP was diagnosed. Thus, dexamethasone (1mg/kg) was initiated for 20 days and then tapered. Corticosteroid Treatment led to a dramatic clinical response and a PLT count returning to the normal range.

Peripheral blood smear (PBS) and CBC were remarkable for anemia (Hemoglobin = 10 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (7 x 103/µL). White blood cell (WBC) count was 6.8 x 103/µL with differentiation (neutrophils 81%, lymphocytes 17% and mixed cells 2%) were normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Hepatitis A, B and C and lupus were all negative. Further workups showed blood sugar (BS) 106 mg/dL, urea 28 mg/dL, aspartate transaminase (AST) 18 U/L, alanine transaminase (ALT) 8 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 135 U/L, sodium 134 mEq/L, potassium 3.9 mEq/L, total bilirubin 0.9 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.1 mg/dL, iron was 36 µg/dL, total iron binding capacity (TIBC) 373 µg/ dl, and ferritin 116 ng/mL.

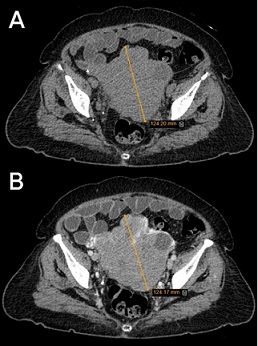

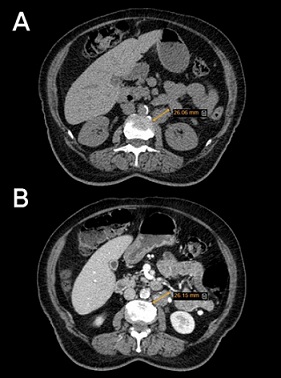

On the third day of hospitalization upper endoscopy was performed for investigation of the gastrointestinal tract malignancies. Biopsy showed chronic gastritis, mild chronic inflammation, and mild atrophy, without dysplasia or metaplasia, and Helicobacter pylori was not detected. Due to mild abdominal pain, abdominopelvic sonography and computed tomography (CT) were performed. Sonography of the pelvis revealed a large heterogeneous mass lesion (132 x 90 mm) posterior extending from the left adnexa into the right adnexa through the cul-de-sac, fluid in the interloop region particularly in the right iliac fossa, omental thickening in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) with a smooth pattern, and two nodules with hypoechoic centers and ill-defined borders. Infiltrative extension of the lesion with a heteroechoic mass (36 x 56 mm) was seen near the medial surface of the right ovary, but the major part of the right ovary was intact; therefore, the mass appeared to originate from the left ovary. Moreover, in the paraaortic region were seen some hypoechoic lymph nodes with a maximum short-axis diameter (SAD) equal to 19 mm in the inferior left renal artery pedicle. Abdominal and pelvic CT scan shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1. Abdominal and Pelvic Computed Tomography Scan without (A) and with contrast (B): an extending solid mass with lobulated borders (maximum axial diameter equal to 12.4 cm) extended over the uterus into the Vesicouterine pouch and invaded to the left partial peritoneum, but there is no evidence of invasion to the bladder, and also a mass adhered to the distal sigmoid.

Figure 2. Abdominal and Pelvic Computed Tomography Scan without (A) and with Contrast (B): two hypodense, ill-defined regions between the right diaphragm and posterosuperior segment of the right lobe of the liver, left paraaortic adenopathy under the renal pedicle 2.6 cm in diameter.

Bone marrow biopsy (BMB) and aspirate (BMA) were performed to rule out causes relative to bone marrow involvement. BMB showed 50% cellularity (appropriate for the patient’s age), mildly increased megakaryocytes with normal morphology, and normal maturation of erythroid and myeloid lineages. Also, there was no evidence of metastatic involvement of BM. BMA results shown in Table 2.

| Parameters | Result | Unit |

| Blasts % | 1 | % |

| Myeloid % | 60 | % |

| Erythroid % | 24 | % |

| Lymphocytes % | 15 | % |

| M:E Ratio | 2.5 | - |

Based on findings of abdominopelvic sonography and CT scan, including ovarian mass, paraaortic lymph node involvement, and elevated cancer antigen 125 (CA-125=1670U/mL), she underwent an ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy and was diagnosed with metastatic HGSOC.

Because of abdominal and pelvic lymphadenopathy (stage IIIa ovarian cancer), surgery was not possible as the primary treatment; therefore, she received four courses of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel (175 mg/m2), carboplatin (AUC 6), and bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every three weeks. Following a favorable response, she underwent optimal cytoreductive surgery, including total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, omentectomy, and lymphadenectomy.

Pathology samples that taken during surgery showed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma which was consistent to HGSOC. Omentum, appendix, mesocolon, outer surface of right ovary, peri-adnexal fibro-adipose tissue, left pelvic lymph node (one of the four lymph nodes) in left and rectal outer surface tumor were involved. postoperatively CA-125 became within normal limit (CA-125=14U/mL), Also, patient received two courses chemotherapy with paclitaxel, carboplatin and bevacizumab.

She was followed for five months without any sings of disease progression.

Discussion

Ovarian cancer is the seventh common cancer (3.7% of all cancers) and the eighth cause of cancer- related deaths (4.7% of all cancer-related deaths) of women around the world in 2020 [5]. HGSOC is the most type of non-mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer and the most common type of ovarian cancer in women. HGSOC is the cause of 70-80% of all deaths in patients with ovarian cancer [6].

There are several hematologic disorders known as PNS, including thrombocytopenia, thrombocytosis, erythrocytosis, anemia, etc. Paraneoplastic ITP is less common in solid tumors than lymphomas [7].

Paraneoplastic ITPs can occur before diagnosis of cancer, concurrent with cancer diagnosis, after chemotherapy, or at recurrence of cancer. In most cases, ITP happened concurrent with a cancer diagnosis. This is not a principle, but it is important that most reported cases of ITP that occurred before cancer diagnosis were non-metastatic cancer [4].

ITP can happen in all ages, races and also genders but mostly incident in children and elder persons [8, 9]. Incidence rates of acute ITP in epidemiologic studies are reported from 1.6 to 3.9 per 100,000 persons in a year for adults, and incidence increases with age. One-fifth of patients with ITP have an underlying disease that categorizes in secondary ITP [9]. ITP can happen secondary to autoimmune disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematous), lymphoproliferative disorders (e.g., chronic lymphocytic leukemia), malignancy, infection, and drugs [1].

The most common manifestation of ITP is bleeding, which may occur in two-thirds of patients. Bleeding symptoms vary from mild form (e.g., mucocutaneous bleeding) to severe form (e.g., intracranial bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, etc.) [1, 9].

Diagnosis of ITP is proved after exclusion of other causes of thrombocytopenia. A good history taking, physical examination, and laboratory tests can be helpful in ruling out other causes. Differential diagnoses of ITP are thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), aplastic anemia, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), renal or liver disease, pseudo thrombocytopenia, myelodysplastic syndrome, genetic diseases, etc [1].

Treatment goals in ITP are different from person to person based on severity, but the overall goal is to prevent bleeding and retain a PLT count up to 20-30 x 109/L, especially in patients who have symptoms (e.g., bleeding); all therapies must have the lowest possible toxicity [10]. The approach to ITP in adults and children has a similar base, but in adults it is more complicated. In adults’ initial therapy is corticosteroid (e.g., dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, and prednisolone), intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), and anti-D, and subsequent therapies are divided into medical therapy (e.g., rituximab, thrombopoietin receptor agonists, and fostamatinib) and surgical therapy (splenectomy) in cases that don’t respond to initial therapies and with consideration of age and comorbidities [10]. Although corticosteroid and corticosteroid+ IVIg are in first-line ITP treatment, a systematic review has shown that response to corticosteroid and corticosteroid+ IVIg in patients with ITP secondary to malignancies (e.g., solid tumors and lymphoproliferative disorders) is lower than response in primary ITP, but response to splenectomy and TPO-RAs were the same in both types. Overall, ITP secondary to malignancy has a negative association with a satisfactory response to first-line treatment [11].

Recent advances in targeted therapy particularly for ovarian cancer, including Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors such as Olaparib, Niraparib, and Rucaparib, have significantly improved outcomes for both newly diagnosed and relapsed patients [12]; these new treatments could be powered by genome studies and machine learning for identifying appropriatechemotherapy regimen for patients [13, 14].

Limitations

As with any single case report, the findings presented here cannot be generalized to the population. While selection bias is not applicable to case reports, this presentation may not represent typical patterns of ITP or ovarian cancer. The relatively short follow-up period limits conclusions about long-term outcomes and recurrence risk. It is also possible that comorbid conditions, such as diabetes associated with ITP [14]. Because the coexistence of metastatic ovarian cancer and ITP is rare, broader conclusions require accumulation of similar cases through collaborative registries or multi-center studies.

In conclusion, in this report, we presented a 63-year- old female admitted to the hospital with non-specific symptoms and ITP which further workups led to diagnosis of metastatic HGSOC. Our patient demonstrated a dramatic response to corticosteroid administration. ITP in the context of malignant disease is a rare phenomenon, and to the best of our knowledge, it is exceptionally rare in ovarian cancer, particularly in metastatic cases. This underscores the importance of considering malignancy as a potential underlying cause of ITP in clinical practice. Another point from this case is that even high-grade cancers can remain silent and present with non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, loss of appetite etc.

Acknowledgments

Statement of Transparency and Principals

• Author declares no conflict of interest

• Study was approved by Research Ethic Committee of author affiliated Institute.

• Study’s data is available upon a reasonable request.

• All authors have contributed to implementation of this research.

References

- Immune thrombocytopenia Kistangari G, McCrae KR . Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America.2013;27(3). CrossRef

- Recent advances in the mechanisms and treatment of immune thrombocytopenia Provan D, Semple JW . EBioMedicine.2022;76. CrossRef

- Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, Michel M, Provan D, Arnold DM , Bussel JB , et al . Blood.2009;113(11). CrossRef

- Paraneoplastic autoimmune thrombocytopenia in solid tumors Krauth M, Puthenparambil J, Lechner K. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology.2012;81(1). CrossRef

- Epidemiology of ovarian cancer Gaona-Luviano P, Medina-Gaona LA , Magaña-Pérez K. Chinese Clinical Oncology.2020;9(4). CrossRef

- Rethinking ovarian cancer II: reducing mortality from high-grade serous ovarian cancer Bowtell DD , Böhm S, Ahmed AA , Aspuria P, Bast RC , Beral V, Berek JS , et al . Nature Reviews. Cancer.2015;15(11). CrossRef

- Immune thrombocytopenia among patients with cancer and its response to treatment Ayesh Haj Yousef MH , Alawneh K, Zahran D, Aldaoud NH , Khader Y. European Journal of Haematology.2018. CrossRef

- The epidemiology of immune thrombocytopenic purpura Fogarty PF , Segal JB . Current Opinion in Hematology.2007;14(5). CrossRef

- Epidemiology and Clinical Manifestations of Immune Thrombocytopenia Kohli R, Chaturvedi S. Hamostaseologie.2019;39(3). CrossRef

- Updated international consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia Provan D, Arnold DM , Bussel JB , Chong BH , Cooper N, Gernsheimer T, Ghanima W, et al . Blood Advances.2019;3(22). CrossRef

- Treatment of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) secondary to malignancy: a systematic review Podda GM , Fiorelli EM , Birocchi S, Rambaldi B, Di Chio MC , Casazza G, Cattaneo M. Platelets.2022;33(1). CrossRef

- Impact of Olaparib, Niraparib, Rucaparib therapies on Newly Diagnosed and Relapsed Ovarian Cancer -Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Devi S, Chandrababu R. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2025;26(6). CrossRef

- Enhancing Personalized Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer: Integrating Gene Expression Data with Machine Learning Khalsan M, Al-Alloosh F, Al-Khafaji ASK . Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2025;26(3). CrossRef

- Successful treatment of primary immune thrombocytopenia accompanied by diabetes mellitus treated using clarithromycin followed by prednisolone Ohe M, Shida H, Horita T, Furuya K, Hashino S. Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics.2018;12(2). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2026

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times