Prostate Cancer in Iraq: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Epidemiology, Clinical Landscape, Challenges, and Public Health Strategies

Abstract

Prostate cancer in Iraq is an escalating public health concern, with incidence rates significantly increasing over the past two decades. Although Iraq’s stated incidence is lower than worldwide and regional averages, the abnormally high mortality-to-incidence ratio (Middle East’s MIR of 12.35 vs. Europe’s 3.00) suggests considerable underdiagnosis and late-stage presentation. This literature review was conducted through a systematic search of Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, and regional journals (2000–2025), by searching the terms such as “Iraq,” “prostate cancer,” “risk factors,” “screening,” “epidemiology,” and “treatment” to identify the original studies, reviews, and official reports concerning Iraqi populations. The majority of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages (Stage III or IV) due to a lack of awareness, inadequate screening, and shortcomings in healthcare infrastructure, leading to delayed discovery. Regional hotspots such as Karbala and Baghdad have heightened prevalence, possibly due to environmental exposures and lifestyle variables, including smoking. Genetic variants (e.g., CYP1A1, GSTM1) correlate with increased risk, indicating specific regional susceptibilities. Despite governmental claims of free cancer treatment, many patients experience considerable financial hardship, often seeking costly therapy abroad. Public awareness is insufficient, and physician training in screening is lacking. Surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy are treatment choices, although they aren’t always easy to get. To turn things around, we need to make cancer registries stronger, make it easier to find cancer early, and improve public education and healthcare infrastructure. Comprehensive national strategies are crucial to address these systemic deficiencies and mitigate the rising incidence of prostate cancer in Iraq.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is acknowledged worldwide as a significant public health issue, ranking as the second most prevalent malignancy in males and the fifth highest cause of cancer-related mortality globally. Global estimations for 2020 revealed approximately 1.4 million new cases and 375,000 fatalities, with predictions forecasting a substantial rise to 1.7 million new cases and 500,000 deaths worldwide by 2030. In 2020, the Middle East documented approximately 50,000 newly diagnosed cases, representing 3.7% of the global incidence [1-3].

Prostate cancer is a major health issue in Iraq, where it is one of the ten most common cancers in men. It is the sixth most prevalent cancer in men in some places, including Karbala province, and it makes up 7.1% of all cancer cases.1 National data show that the number of cases has gone up a lot over the past twenty years, which shows how important it is for public health [4, 5].

This in-depth review of the literature aims to combine and assess the current research on prostate cancer in Iraq. The goal is to give a full picture of its epidemiological profile, clinical presentation, risk factors, current awareness and screening status, treatment landscape, socioeconomic effects, and current or proposed public health actions. This synthesis is important for helping to establish targeted interventions and strategies to deal with this growing health problem.

Methodology

This review employed a narrative methodology to discover, assess, and synthesize pertinent studies about prostate cancer in Iraq. Databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and regional journals were queried using keywords including “prostate cancer,” “Iraq,” “epidemiology,” “risk factors,” “screening,” and “treatment.” The investigation encompassed articles from 2000 to 2025. The inclusion criteria were original research, reviews, and official publications pertaining to prostate cancer within the Iraqi population, published in English.

The exclusion criteria were research that were irrelevant to Iraq, non-peer-reviewed publications, and those concentrating exclusively on animal or laboratory models. A narrative synthesis was employed to amalgamate epidemiological, clinical, genetic, and socioeconomic data from the literature. Data from prominent national reports and international organizations (e.g., WHO, GLOBOCAN, IAEA) were used to substantiate and contextualize the conclusions. the AMSTAR-2 is utilized to evaluate the methodological rigor of systematic reviews and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational research. Each manuscript was evaluated individually by both reviewers; any inconsistencies were resolved through conversation until an agreement was achieved. We acknowledge that Iraqi cancer registry data may be affected by underreporting, delayed entries, and geographical discrepancies in coverage. Registry numbers were systematically cross-verified with hospital-based series and GLOBOCAN estimates to contextualize and reduce these biases.

Epidemiology and Disease Burden in Iraq

The epidemiological profile of prostate cancer in Iraq shows a complex picture with rising rates, particular geographic distributions, and a big difference from global and regional averages [1].

Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality Rates

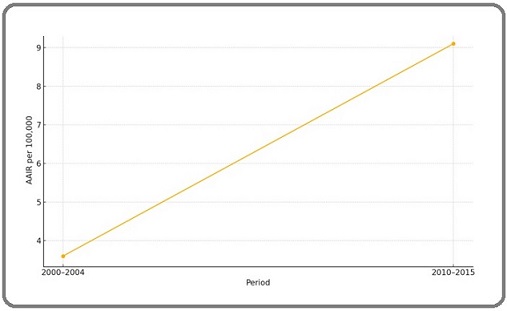

The age-adjusted incidence rate (AAIR) of prostate cancer has gone up a lot in Iraq, except in the Kurdish area. From 2000 to 2004, the rate was 3.60 per 100,000 people. From 2010 to 2015, it rose to 9.10 per 100,000 people. In 2008, the Iraqi Cancer Board reported 246 new cases, which gave an incidence rate of 1.56 per 100,000 people [4, 5].

The incidence rate in Karbala province is a good example of this development. It went from 3.15 per 100,000 in 2012 to 6.79 per 100,000 in 2020. During the nine years, 265 prostate cancer patients were seen at Al- Hussein Cancer Center. Prostate cancer cases made up between 2.32% and 4.32% of all tumors found [1].

GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates that Iraq has an incidence rate of 8.64 prostate cancer cases per 100,000 people, a prevalence rate of 64.564 cases per 1,000 people, and a death rate of 2.523 cases per 100,000 people [6]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 171 people died from prostate cancer in Iraq in 2020. This was 0.12% of all deaths, and the age-adjusted mortality rate was 2.81 per 100,000 people, making Iraq the 176th country in the world for prostate cancer deaths [7].

Temporal and Geographic Trends

The incidence rates of prostate cancer in Iraq have shown a substantial increase over the past sixteen years, indicating a growing burden [4, 5]. Projections for the Middle East, including Iraq, anticipate a markedly higher rise in prostate cancer incidence by 2050 compared to Europe and North America [8].

Spatial autocorrelation analysis has revealed significant clustering of prostate cancer incidence within Iraq. Hotspots, areas with persistently high incidence rates, were identified in districts such as Al-Rissafa, Al-Manathera, Al-Kufa, Al-Hilla, Al-Hindiya, and Karbala during 2005-2009. By 2010-2015, these hotspots expanded to include Al-Mussyab, Al-Adhamiya, Al-Sadir, and Daquq, indicating an evolving geographic pattern of high-burden areas. Conversely, coldspots, areas with lower incidence, were identified particularly in Al-Anbar and Ninewa provinces [4, 5]. The identification of these specific hotspots suggests that localized factors may be at play beyond general national trends. The consistent appearance of certain regions, such as Al-Rissafa, Al-Hilla, and Karbala, as high-burden areas over time points to a persistent higher prevalence of prostate cancer in these localities. This non-random distribution necessitates a closer examination of potential underlying causes, which could encompass localized environmental exposures (e.g., industrial pollution or conflict-related contaminants), specific lifestyle patterns (such as the high smoking rates observed in Baghdad suburbs), or even disparities in healthcare access and diagnostic capabilities within Iraq. While direct causal links between specific hotspots and their origins are not explicitly detailed in the available literature, the clear spatial clustering serves as a strong epidemiological signal, guiding future research to pinpoint precise localized risk factors and enabling the design of highly targeted public health interventions and resource allocation strategies for the most affected populations [5, 9, 10].

Age Distribution at Diagnosis

Prostate cancer predominantly affects older men in Iraq, consistent with global patterns. In Karbala, the median age at diagnosis was 70 years, with patient ages ranging from 47 to 95 years. The most affected age group was 61-70 years, accounting for 47.55% of cases, followed by 71-80 years, comprising 30.57% [1]. Similarly, in Erbil, the median age at diagnosis was 71 years [11]. A population-based analysis of 1,366,129 prostate cancer patients from the U.S. SEER database (1975–2015) revealed a median age at diagnosis of 68 years (IQR 61–75), with the majority of cases occurring in men aged 60 and older, underscoring that prostate cancer primarily affects older men globally [12].

Comparative Analysis: Iraq vs. Middle East and Global Context

Iraq’s reported incidence rate (8.64 per 100,000) is notably lower than the global average of 33.449 per 100,000 and the Middle East regional average of 20.626 per 100,000. Similarly, its prevalence, mortality, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) are reported to be lower than both regional and global averages [6].

However, a critical observation emerges when comparing Iraq and the broader Middle East to Western countries: despite a lower reported incidence, the region exhibits a significantly higher Mortality-to-Incidence Ratio (MIR). The Middle East’s MIR is 12.35, starkly contrasting with 3.00 for Europe and North America [13]. This suggests that a larger proportion of diagnosed cases in the Middle East, including Iraq, result in death. This apparent contradiction lower reported incidence but higher MIR points towards a significant issue of underdiagnosis and late-stage presentation rather than a genuinely lower disease occurrence. If many prostate cancer cases are not detected until they are advanced or symptomatic, they are less likely to be amenable to curative treatments, naturally leading to a higher mortality rate relative to the number of identified cases. This phenomenon is further exacerbated by acknowledged data limitations in conflict-affected regions like Iraq, where factors such as underreporting, constraints in healthcare infrastructure, and political instability can significantly bias epidemiological estimates and understate the actual disease burden [6]. Consequently, the “low incidence” is likely an artifact of detection limitations, masking a more severe, unaddressed public health crisis.

Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs)

The DALYs for prostatic cancer in Iraq are reported as 52.995 per 100,000 population, which is lower than the regional average of 105.272 per 100,000 and the global average of 205.627 per 100,000 [6]. Similar to the incidence and mortality rates, this lower DALYs figure may also be influenced by the aforementioned data limitations and challenges in data collection and reporting in conflict-affected regions (Table 1), (Table 2), (Figure 1).

| Metric (per 100,000 population, unless stated) | Iraq (2020) | Middle East Average (2020) | Global Average (2020) |

| Incidence Rate | 8.64 | 20.626 | 33.449 |

| Prevalence Rate (per 1,000 population) | 64.564 | 163.288 | Not Specified |

| Mortality Rate | 2.523 | 5.32973 | 10.922 |

| DALYs | 52.995 | 105.272 | 205.627 |

| Source: (6) |

| Period | Top 5 Districts by AAIR (per 100,000) | Hotspots (High-High Clusters) | Coldspots (Low-Low Clusters) |

| 2000-2004 | Ain-Al-Tamur (11.50), Daquq (10.70), Al-Karkh (8.60), Rissafa (7.90), Al-Hawiga (7.80) | Random Distribution | Random Distribution |

| 2005-2009 | Al-Najaf (16.30), Daquq (11.40), Al-Karkh (11.30), Al-Hilla (9.70), Rissafa (8.60) | Al-Rissafa, Al-Manathera, Al-Kufa, Al-Hilla, Al-Hindiya, Karbala, Kirkuk, Al-Najaf | Rawa (Al-Anbar) |

| 2010-2015 | Al-Karkh (18.20), Al-Najaf (15.80), Tikrit (15.20), Al-Hilla (14.50), Karbala (14.20) | Al-Rissafa, Al-Adhamiya, Al-Sadir, Al-Karkh, Al-Mussyab, Al-Hilla, Al-Hindiya, Daquq, Kirkuk | Ana (Al-Anbar), Rawa (Al-Anbar), Al-Hatra (Ninewa), Al-Baaj (Ninewa), Sinjar (Ninewa) |

| Source: [5, 14] |

*Spatial clusters identified using Local Moran’s I statistic (α = 0.05; 999 permutations).

Figure 1. A Line Graph Illustrating the Rise in Age Adjusted Incidence Rates of Prostate Cancer in Iraq between 2000-2015.

Clinical Characteristics and Diagnostic Landscape

The clinical profile of prostate cancer in Iraq underscores a concerning trend of advanced disease at presentation, coupled with specific histopathological patterns.

Common Presenting Symptoms and Histopathological Subtypes

In Karbala, irritative symptoms were the most common presentation, affecting 58.11% of patients. Other significant symptoms included bone pain (25.28%) and obstructive symptoms (10.95%), with a small proportion (5.66%) being asymptomatic [1]. Similarly, in Erbil, 81.6% of patients presented with urinary tract symptoms [11]. The high prevalence of symptoms such as bone pain or even neurological signs and symptoms is a critical indicator, frequently associated with metastatic or advanced disease and novel diagnostic test can improve their detection [15, 16].

Regarding histopathology, adenocarcinoma is overwhelmingly the predominant subtype. In a study conducted at Medical City in Baghdad, acinar adenocarcinoma represented 89.85% of cases [17]. Less common subtypes observed included squamous cell carcinoma (3.02%) and transitional cell carcinoma (1.13%) [1]. Notably, squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate is considered an aggressive form with a poor prognosis, often associated with a median post-diagnosis survival of only 14 months [18].

Stage at Diagnosis: Prevalence of Advanced Disease

A critical and consistent finding across multiple studies is the high proportion of patients diagnosed at advanced stages. In a singular tertiary referral centre research with 559 patients (522 with staging data), 48.5% of Iraqi patients exhibited Stage IV illness, with 17% presenting distant metastases at diagnosis. In contrast, U.S. SEER statistics (2007–2012) indicate that only 6.4% presented with metastases [19]. In the Iraqi segment of a four-nation Middle Eastern study, 25% of patients exhibited Stage III and 52% Stage IV disease, indicating that 77% had locally progressed or metastatic cancer at the time of diagnosis [20]. Among 582 cases at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (12% Iraqi), 57.6% of the Iraqi subgroup were diagnosed at Stage IV, versus 22.6% overall [21]. A retrospective review across six Middle Eastern countries (including Iraq) of 1,136 patients found 54% presenting with Stage IV disease at diagnosis, and 35% with clinical T3/T4 disease [22].

In Karbala, more than half of the patients (51.32%) presented as stage IV [1]. Similarly, in Erbil, a striking 62.7% of patients were diagnosed at stage IV, with an additional 17.9% at stage III [11]. At Medical City, the majority of patients were diagnosed at moderately advanced or advanced TNM stages, with 57.97% at stage III, and 78.26% of metastatic cases specifically identified as stage IV [17]. Advanced imaging techniques are demonstrating significant value. Diffusion-weighted MRI in an Iraqi cohort identified and localised prostate lesions with 85% sensitivity and 78% specificity (κ = 0.72 compared to histology), providing a non-invasive supplement to enhance biopsy targeting and treatment planning [23]. This consistently high percentage of stage IV diagnoses is not merely a statistic but a critical indicator of systemic failures in early detection. When over half of prostate cancer patients are diagnosed at Stage IV, it signifies that the disease has already spread beyond the prostate, making curative treatment much less likely and significantly worsening prognosis. This stark reality strongly implies a profound lack of effective early screening programs and/or low public awareness that would prompt earlier medical consultation. Patients are not found via normal examinations or screening tests; instead, they present with advanced, frequently symptomatic disease. This delayed diagnosis alters the therapeutic emphasis from curative measures to palliative care, escalates treatment complexity and expenses, and eventually leads to increased morbidity and mortality, albeit potentially lower reported incidence rates. This phenomenon is primarily ascribed to insufficient information and attitudes towards screening programs, highlighting a critical public health issue that necessitates immediate action in awareness and screening infrastructure [17] (Table 3).

| Stage at Diagnosis | Karbala (2012-2020) [N (%)] | Erbil (2016-2021) [N (%)] | Medical City (2018-2022) [N (%)] |

| Stage I | 5 (1.89) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.35) |

| Stage II | 58 (21.89) | 17 (17.9) | 24 (34.78) |

| Stage III | 66 (24.90) | 17 (17.9) | 40 (57.97) |

| Stage IV | 136 (51.32) | 60 (62.7) | 36 (78.26% of metastatic cases) |

| Source | [1] | [11] | [17] |

Risk Factors for Prostate Cancer in Iraq

Genetic Predispositions

Some of the most well-known risk factors for prostate cancer around the world are being older, having a family history of the disease, and having particular genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2. Studies show that BRCA1/2 mutations may be more widespread in some Arab groups. This could explain why illnesses are more or less common and severe in the area [24].

Studies of Iraqi communities have also begun to find particular genetic variants that are connected to a higher risk of prostate cancer, in addition to these general traits. There was a strong link between the CYP1A1 rs1048943 polymorphism and the incidence of prostate cancer in men from Southern Iraq (p=.008) [25]. Also, variations in the glutathione S-transferase (GST) genes, especially GSTM1 and GSTT1, were strongly linked to a higher risk of prostate cancer in Iraqi patients (p<0.05) [26]. A study on the IL-18 gene promoter -137G/C (rs187238) polymorphism found no link between it with the incidence of prostate cancer in the Iraqi Arab community. However,serum IL-18 levels were much higher in patients, suggesting that this gene plays a unique function in the progression or response of the illness [27].

The discovery of some gene variations (CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTT1) that are strongly linked to the incidence of prostate cancer in Iraqi individuals is an important step forward from generic discussions of risk factors. This suggests that the Iraqi people may have a unique genetic susceptibility profile, or that these genetic factors interact in a unique way with the environment in Iraq. This understanding is highly valuable for developing more targeted and effective public health strategies. For example, it could inform the creation of population-specific genetic screening panels for high-risk individuals, leading to more personalized early detection and prevention efforts, rather than relying solely on broad, internationally derived guidelines that may not fully capture the local epidemiological nuances. The finding regarding IL-18 also highlights the complexity of genetic influence, where the polymorphism itself may not confer risk, but its functional impact (elevated serum levels) might still serve as a biomarker.

Lifestyle and Environmental Factors

While definitive evidence for many lifestyle and environmental factors remains limited, smoking, excess body weight, and certain nutritional factors are recognized as potentially increasing the risk of advanced prostate cancer [28]. A study in Baghdad revealed that a substantial majority of prostate cancer patients (80%) were smokers, with 40% consuming three packs daily and 32% having smoked for over 20 years [4]. Obesity and dietary habits are also becoming more prevalent in the Middle East and are highlighted as contributing risk factors for prostate cancer [29].

A unique and critical aspect of environmental risk in Iraq pertains to conflict-related exposures. As a region profoundly affected by prolonged conflict, military exposures to carcinogens are a significant concern [6]. For instance, burn pit smoke, prevalent in Iraq and Afghanistan from 2001-2011, may have contained known carcinogens such as benzene, soot, diesel exhaust particulates, and organic fumes. These exposures are presumptively linked to various cancers, including those of the reproductive system. The use of mustard gas during the Iran-Iraq war (1940s-1980s), a chemical warfare agent, is presumptively linked to several cancers, although prostate cancer is not explicitly listed among them. While the Veterans Administration (VA) has not found evidence of a cancer link from the Qarmat Ali wastewater treatment plant in Iraq (2003), where hexavalent chromium was present, the pervasive presence of potential carcinogens from past conflicts represents a significant, yet largely unquantified, environmental risk factor [30-32].

The mention of burn pits and chemical warfare agents in Iraq’s history introduces a critical, albeit complex, dimension to environmental risk factors. While direct epidemiological studies explicitly linking these specific exposures to prostate cancer incidence in Iraq are not provided, the known carcinogenic nature of substances like benzene (from burn pits) and the general association of burn pit smoke with reproductive system cancers strongly suggest a plausible, unquantified contribution. This implies that the observed prostate cancer patterns in Iraq are not solely attributable to conventional lifestyle factors or genetic predispositions, but may also be influenced by a unique legacy of environmental contamination from prolonged conflict. This unquantified impact represents a significant gap in current understanding and underscores the urgent need for dedicated, long-term epidemiological studies to assess the true burden and specific links between these exposures and prostate cancer in the Iraqi population. Such research is vital for informing public health policy and specialized healthcare provision for affected populations.

Awareness, Screening Practices, and Barriers to Early Detection

Public Awareness Levels and Knowledge Gaps regarding Prostate Cancer Levels

While a high proportion of men in the Middle East (83.8%) have reportedly heard of prostate cancer, this general awareness often lacks depth and accuracy [8]. Only 31.0% correctly identified it as the most common male malignancy, and a concerning 21.8% incorrectly believed it affects both sexes [33]. Knowledge regarding crucial aspects such as screening tools (32.3%), symptoms (45.5%), risk factors (49.4%), and treatments (58.4%) remains limited [34]. Furthermore, there is a prevailing pessimistic outlook, with a mean perception that 75% of prostate cancer patients die from the disease [33]. The majority of individuals obtain health information from unreliable sources, including the internet, television, and friends or relatives, underscoring the urgent need for improved engagement from healthcare providers to disseminate accurate information [34].

Healthcare Professional Screening Practices and Identified Barriers

Prostate cancer screening rates are notably low across the MENA region, including Iraq. A cross-sectional survey revealed that only 34.7% of surveyed physicians routinely perform prostate cancer screenings, with 61.1% of those who do, utilizing Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) tests [35].

Primary barriers identified by physicians include:

● Lack of patient awareness: Cited by 51.2% of participants as the main impediment [35].

● Lack of formal training among physicians: A substantial 65.3% of participants reported having no formal training in prostate cancer screening [35].

Other significant barriers for men include the absence of symptoms (leading to a lack of perceived need for screening), lack of physician recommendation, anxiety surrounding diagnosis, mistrust of physicians, and general misconceptions about the screening process [33]. The data reveals a significant disconnect: a high percentage of the public has “heard of” prostate cancer, but their specific knowledge about its symptoms, risk factors, and especially screening methods (like PSA testing) is alarmingly low. This superficial awareness does not translate into proactive health-seeking behaviors, leading to delayed presentation. Compounding this, a significant majority of physicians report a lack of formal training in prostate cancer screening, and only a minority routinely perform these screenings. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle: patients are not adequately informed to demand screening, and many healthcare providers are not equipped or proactive enough to offer it. This systemic failure in both public education and professional training is a primary driver of the high rate of late-stage diagnoses and, consequently, the elevated mortality-to-incidence ratio observed in the region.

Attitudes Towards Prostate Cancer Screening

While the rate of favorable attitude towards prostate cancer screening in the Middle East was reported at 50.0%, this positive sentiment does not consistently translate into high screening uptake. As noted, screening rates often fall below 30% and sometimes even under 5% , indicating a substantial gap between expressed willingness and actual practice [33].

Present Screening Protocols

The prevalence of screening is minimal: just 34.7% of physicians consistently provide PSA testing, and less than 30% of males indicate they have ever undergone screening, the screening producer [36]:

1- The USPSTF (2023): issues a Grade C recommendation for males aged 55–69, advising individualised decision-making, and a Grade D recommendation for men aged 70 and above.

2- AUA/SUO (2023): Strong recommendation for PSA screening biennially to quadrennially in men aged 50–69; underscore the need of collaborative decision-making (Evidence Level B).

3- The ACS (2023) recommends initiating screening at age 50 for average-risk males and at age 45 for high-risk populations, such as those with a family history or Black men (Table 4).

| Category | Specific Barrier | Percentage (where available) | Source |

| Healthcare Professional Identified Barriers | Lack of patient awareness | 51.20 % | [35] |

| Lack of formal training among physicians | 65.30 % | [35] | |

| Limited access to screening equipment | Implied (suggested improvement) | [35] | |

| Patient Identified Barriers | Lack of awareness of symptoms, complications, and screening procedures | Not specified, but a primary factor | [34] |

| Absence of symptoms | Not specified | [34] | |

| Lack of physician recommendation | Not specified | [34] | |

| Anxiety (fear of diagnosis, impact on sexuality) | Not specified | [34] | |

| Mistrust of physicians | Not specified | [34] | |

| Misconceptions about the screening process | Not specified | [34] | |

| Unreliable information sources (internet, TV, friends/relatives) | Majority of participants | [34] |

Treatment Modalities and Outcomes

Overview of Available Surgical Interventions

For patients with localized or locally advanced prostate cancer, various surgical options are available in Iraq, aligning with international guidelines. These include radical prostatectomy (performed in 27.53% of cases in one study), robotic prostatectomy (17.39%), bilateral orchiectomy (7.24%), and surgical castration (21.74%). Robotic or laparoscopic prostatectomy is often favored due to its reported better efficacy and fewer side effects. Despite the availability of these procedures, a notable proportion of patients (18 cases in the aforementioned study) with localized or locally advanced disease did not undergo surgery [17, 37].

Non-Surgical Treatment

Beyond surgery, other treatment modalities for prostate cancer in Iraq include radiotherapy and Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT). For advanced or metastatic disease, palliative approaches such as palliative surgery, palliative radiotherapy, Radiotherapy Toxicity and Long-Term Outcomes and palliative chemotherapy are also part of the treatment spectrum, alongside anti-androgens [17, 38].

Challenges in Managing Advanced and Metastatic Disease

A significant challenge in Iraq is the management of advanced and metastatic prostate cancer. A high proportion of patients with metastatic disease (76.08% in one study) did not undergo surgery. This reflects the inherent difficulty in managing metastatic patients and is consistent with international guidelines that typically recommend ADT and palliative care for advanced stages, rather than curative surgery. The disparity in treatment access and management of advanced disease is a critical concern. While surgical options, including advanced techniques like robotic prostatectomy, are available and performed for localized disease, a very high percentage of metastatic patients do not undergo surgery. This suggests a critical gap in the comprehensive management of advanced disease. This gap could stem from several factors: a lack of appropriate surgical capacity for complex metastatic cases, patients being too debilitated for surgery, or a clinical preference for non-surgical palliative approaches. The additional information that patients from Baghdad are explicitly seeking “affordable” and “advanced” prostate cancer surgery in India strongly implies that local healthcare infrastructure in Iraq may be perceived as inadequate or prohibitively expensive for comprehensive, high-quality treatment, especially for advanced stages [20, 39, 40].

This situation places a significant burden on patients and their families, often forcing them to seek care abroad, which can lead to delayed or forgone treatment and highlights a systemic shortfall in specialized cancer care provision within Iraq.

Socioeconomic and Financial Impact of Prostate Cancer

Correlation with Socioeconomic Indicators

Analysis of projected increases in prostate cancer incidence in the Middle East by 2050 reveals a strong positive correlation with income level (p=.006). Higher income categories are projected to exhibit a greater percentage increase in incidence, with median changes of 157% for lower-middle-income countries versus 334% for high-income countries. No significant association was observed with the Human Development Index (HDI) [8]. This finding, where higher income levels correlate with a greater projected increase in prostate cancer incidence in the Middle East, initially appears counter-intuitive, as one might expect higher income to correlate with better health outcomes. However, in the context of cancer incidence, this positive correlation likely reflects improved access to diagnostic services and screening among wealthier populations. Individuals with higher incomes are more likely to afford or access private healthcare, undergo routine check-ups, and receive PSA testing, leading to a higher rate of diagnosed cases. This suggests that the “increased incidence” in higher-income groups may, in part, be an artifact of better detection rather than a true higher biological prevalence. Conversely, it implies a significant hidden burden of undiagnosed prostate cancer in lower-income populations who lack such access. This paradox underscores the need for equitable access to diagnostic services across all socioeconomic strata to reveal the true disease burden and ensure no segment of the population is left behind in cancer control efforts.

Financial Distress and Costs of Treatment for Patients and Families

Despite a substantial allocation of over 45% of Iraq’s annual health budget to cancer treatment, with chemotherapy, surgeries, and diagnostic tests reportedly provided free of charge , patients frequently face severe financial distress. The existence of a black market where a single vial of chemotherapy can exceed $700 highlights critical shortages of essential medications. Furthermore, patients often find it necessary to seek international donors for transplant materials, incurring costs ranging from 30,000 to 50,000 [41] For those traveling abroad for treatment, such as to Lebanon, average total expenditures ranged from US 20,531 for 1-4 visits to US98,852 for five or more visits. Lacking private health insurance, patients are compelled to resort to selling possessions, raising money through donations, taking on debt, and even selling their homes to fund these essential treatment trips [42]. The initial statement that “over 45% of Iraq’s annual health budget is dedicated to cancer treatment” and that services like “chemotherapy, surgeries, and diagnostic tests” are “provided free of charge” creates an impression of robust public healthcare support. However, this is immediately and starkly contradicted by subsequent details: the existence of a black market for chemotherapy at exorbitant prices, critical shortages of medications and transplant materials, and the necessity for patients to fund international treatment by selling possessions, incurring debt, or even selling their homes.

This reveals a profound systemic failure: while policies may declare services “free,” the reality on the ground is that these services are either unavailable, insufficient, or require patients to navigate a costly informal system. This implies that the actual financial burden on Iraqi prostate cancer patients is catastrophic, pushing families into poverty and likely leading to delayed, incomplete, or forgone treatment, which directly impacts patient outcomes and survival. It highlights a critical gap between policy intent and practical implementation, driven by supply chain issues, infrastructure limitations, and potentially corruption.

Public Health Initiatives and Policy Recommendations

Current National Cancer Control Strategies and Progress in Iraq

The 2021 IAEA-IARC-WHO imPACT evaluation gave Iraq suggestions on how to improve cancer control in the country. Iraq has made progress in following these suggestions. Some important things that have happened are better communication between the Iraqi Cancer Board and the Ministry of Health Noncommunicable Disease Unit. The Ministerial directive that makes it easier to prescribe opioids to terminally ill patients is also a good move toward palliative treatment. Iraq has also said that it is committed to creating a national cancer control strategy and plan that will include all aspects of cancer control, from prevention to end-of-life care, and that will help healthcare workers figure out what training they need most [43].

Recommendations for Strengthening Cancer Registries and Data Collection

One of the biggest problems in the Middle East and North Africa, including Iraq, is that there aren’t any complete cancer registries [35]. To fully understand the true burden of prostate cancer and to create effective health policies and make the best use of resources, we need better cancer registries [1]. The Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) have started projects to rebuild supporting infrastructure and make the cancer registry system better, recognizing how important it is for managing cancer [44].

Limitations and Future Research

Limitations

Selection Bias

The majority of studies considered were hospital- based case series or registry analyses, which may disproportionately reflect people with more severe conditions or enhanced access to healthcare. Community instances, especially from rural or conflict-affected regions, may be underestimated.

Data Quality Concerns

Iraqi cancer registries demonstrate underreporting, delayed entry, and variable geographical representation. The inconsistency in diagnostic criteria, staging definitions, and record-keeping hinders comparisons between studies.

Variability in Research Methodologies

The employment of multiple approaches (retrospective cohorts, cross-sectional surveys, narrative reviews) and differing quality evaluation instruments constrains our capacity to conduct quantitative synthesis or meta- analysis.

Unobserved Confounding Variables

The inconsistent capture of socioeconomic position, environmental exposures, and genetic origins raises the potential for residual confounding in the observed correlations.

Limited Statistical Power

Several key studies had small cohorts (e.g., n = 32 in the PSA study), leading to wide confidence intervals and reduced ability to detect moderate effects.

Uncertain Precision of Estimates

Reported incidence rates (e.g., AAIR 8.64 per 100,000) frequently lack defined uncertainty in several sources; where applicable, we reference 95% confidence intervals (e.g., 7.12–10.52).

Assumptions of geographical Methodology

The discovery of hotspots and cold spots by Local Moran’s I presupposes geographical stationarity and a certain neighborhood weighting (queen contiguity), factors sometimes overlooked, hence constraining repeatability.

Omission of Comparative Significance Testing

Despite Iraq’s MIR (12.35) differing from that of Europe/North America (3.00), no formal chi-square or percentage test was conducted to establish statistical significance.

Confounding in Correlational Analyses

Income–incidence correlations failed to account for significant confounders (e.g., diagnostic ability, urbanisation), highlighting the necessity for future multivariable models.

Future Research

1. Prospective, Population-Based Cohorts: Formulate longitudinal cohorts in under-represented provinces (e.g., Anbar, Ninewa) to document incidence, staging, and outcomes in urban and rural environments.

2. Community Screening Studies: Deploy mobile screening units utilising standardised PSA and DRE techniques in high-incidence and underserved areas to assess actual prevalence and enhance early-stage detection.

3. Registry Enhancement Pilot Initiatives: Initiate focused pilots that incorporate electronic case reporting in designated districts, supplemented by data-quality assessments, to formulate scalable models for national deployment.

4. Exposure-Specific Case-Control Studies: Recruit soldiers and civilians with verified conflict-related exposures (burn pits, chemical agents) and matched controls to directly evaluate prostate cancer risk.

5. Genetic and Environmental Interaction Analyses: Perform genome-wide association studies in Iraqi subpopulations, alongside comprehensive exposure histories, to clarify gene-environment interactions and discover actionable biomarkers.

In conclusion, prostate cancer in Iraq is a complicated and growing public health problem. Even while the indicated incidence rates look lower than the global average, this hides a lot of cases that go undiagnosed or are diagnosed too late. The fact that most patients are diagnosed only at advanced stages of the disease and the fact that mortality-to-incidence ratios are excessively high show this. The epidemiological landscape is changing as the number of cases rises over time, certain geographic areas become hotspots for certain contributing factors, and scientists learn more about certain genetic predispositions in the Iraqi population.

There are a lot of complicated problems that make it hard to treat prostate cancer in Iraq. This includes a lack of knowledge among both the general public and healthcare professionals, which leads to inadequate screening procedures. The situation is made worse by a lack of qualified healthcare workers and working medical equipment, as well as a lot of financial stress on patients and their families, which often forces them to seek expensive treatment abroad even though the government offers “free” care. There are chances for major intervention in improving national cancer registries to get accurate data, running targeted and culturally appropriate awareness campaigns to fill in knowledge gaps, making big as much as possible investments in the education of healthcare professionals and oncology infrastructure, and making sure that everyone has fair access to important medications and full care, including a lot of palliative and psychosocial support.

Acknowledgments

Statement of Transparency and Principals

• Author declares no conflict of interest

• Study was approved by Research Ethic Committee of author affiliated Institute.

• Study’s data is available upon a reasonable request.

• All authors have contributed to implementation of this research.

References

- Pattern of Prostate Cancer in Karbala Province of Iraq: Data from Developing Country Mjali A, Agha RTMF , Al-Shammari HHJ , Alwakeel AF , Sedeeq AO , Abbas NT , et al . Asian Pac J Cancer Care.2025;10(1):11-5. CrossRef

- The burden of prostate cancer in North Africa and Middle East, 1990-2019: Findings from the global burden of disease study Abbasi-Kangevari M, Saeedi Moghaddam S, Ghamari S, Azangou-Khyavy M, Malekpour M, Rezaei N, Rezaei N, et al . Frontiers in Oncology.2022;12. CrossRef

- Incidence of Prostatic Carcinoma in Transurethral Resection Specimen Hussein SA , Al-Khafaji KR . Iraq Medical Journal.2021;5(2). CrossRef

- Assessment of contributing risk factors for patients with prostate cancer in Capital of Baghdad Khudur K. Kufa Journal for Nursing Sciences.2012;2(2). CrossRef

- Spatial Analysis Of Prostate Cancer Incidence In Iraq During 2000-2015 Al-Hashimi MM . Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine.2021;21(1):72-80.

- Epidemiological Analysis of Prostatic Cancer: Incidence, Prevalence, Mortality, and Disability Burden in Middle Eastern Countries Malik A, Omar A, Bayan Q, Samer AR , Hassan A, Khalid AB , et al . Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology.2025;10(2):393-400.

- Iraq: Prostate Cancer. World Life Expectancy .

- Projected Prostate Cancer Incidence in the Middle East by 2050: Socioeconomic Disparities and Future Implications Parisi J, Tuac Y, Argun O, Kearney G, Chen LW , Aynaci O, Pervez N, et al . JCO global oncology.2025;11. CrossRef

- Environmental pollutions associated to conflicts in Iraq and related health problems Al-Shammari AM . Reviews on Environmental Health.2016;31(2). CrossRef

- Prevalence of smoking habits among the Iraqi population in 2021 Noori CM , Saeed MAH , Chitheer T, Ali AM , Ali KM , Jader JA , Ali EN , Rostam HM . Public Health Toxicology.2024;4(4). CrossRef

- Clinical and histopathological characteristics of prostate cancer in Erbil city/Iraq Sulaiman LR . Zanco Journal of Medical Sciences (Zanco J Med Sci).2024;28(3):489-500.

- Prostate cancer epidemiology and prognostic factors in the United States Abudoubari S, Bu K, Mei Y, Maimaitiyiming A, An H, Tao N. Frontiers in Oncology.2023;13. CrossRef

- Burden of prostate cancer in the Middle East: A comparative analysis based on global cancer observatory data Kearney G, Chen M, Mula-Hussain L, Skelton M, Eren MF , Orio PF , Nguyen PL , D'Amico AV , Sayan M. Cancer Medicine.2023;12(23). CrossRef

- Spatial Analysis Of Prostate Cancer Incidence In Iraq During 2000 AL-Hashimi MM . .

- A case report of prostate cancer with leptomeningeal metastasis Dehghani M, PeyroShabany B, Shahraini R, Fazilat-Panah D, Hashemi F, Welsh JS , Javadinia SA . Cancer Reports (Hoboken, N.J.).2022;5(8). CrossRef

- The Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Circulating MicroRNAs in the Assessment of Patients With Prostate Cancer: Rational and Progress Samami E, Pourali G, Arabpour M, Fanipakdel A, Shahidsales S, Javadinia SA , Hassanian SM , Mohammadparast S, Avan A. Frontiers in Oncology.2021;11. CrossRef

- Observational study of surgical treatment of prostate cancer in Iraq Yaseen WK . Onkologia i Radioterapia.2023;17(7).

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate Mohan H, Bal A, Punia RPS , Bawa AS . International journal of urology.2003;10(2):114-6.

- High rates of advanced prostate cancer in the Middle East: Analysis from a tertiary care center Daher M, Telvizian T, Dagher C, Abdul-Sater Z, Massih SA , Chediak AE , Charafeddine M, et al . Urology Annals.2021;13(4). CrossRef

- Prostate cancer across four countries in the Middle East: a multi-centre, observational, retrospective and prognostic study El-Karak F, Shamseddine A, Omar A, Haddad I, Abdelgawad M, Naqqash MA , Kaddour MA , Sharaf M, Abdo E. Ecancermedicalscience.2024;18. CrossRef

- Prostate cancer stage at diagnosis: First data from a Middle-Eastern cohort. Mukherji D, Abed El Massih S, Daher M, Chediak A, Charafeddine M, Shahait M, Temraz SN , et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology.2017;35(6_suppl). CrossRef

- Prostate cancer presentation and management in the Middle East Sayan M, Langoe A, Aynaci O, Eren A, Eren ME , Kazaz IO , Ibrahim Z, et al . BMC urology.2024;24(1). CrossRef

- The Value of Diffusion Weighted MRI in the Detection and Localization of Prostate Cancer among a Sample of Iraqi Patients Wahid HMA , Al-Mosawe AM , Kareem TF , Awn AK , Nayyef QT . AL-Kindy College Medical Journal.2020;16(2). CrossRef

- Next-generation sequencing of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Moroccan prostate cancer patients with positive family history Salmi F, Maachi F, Tazzite A, Aboutaib R, Fekkak J, Azeddoug H, Jouhadi H. PloS One.2021;16(7). CrossRef

- Association of CYP1A1 rs1048943 Polymorphism with Prostate Cancer in Iraqi Men Patients Hoidy WH , Jaber FA , Al-Askari MA . Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2019;20(12). CrossRef

- Polymorphisms of glutathione-S-transferase M1, T1, P1 and the risk of prostate cancer: a case-control study Sivonová M, Waczulíková I, Dobrota D, Matáková T, Hatok J, Racay P, Kliment J. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research: CR.2009;28(1). CrossRef

- IL-18 Gene Polymorphisms Impacts on Its Serum Levels in Prostate Cancer Iraqi Patients Shkaaer MT , Utba NM . Iraqi Journal of Science.2019. CrossRef

- Dietary Factors and Risk of Advanced Prostate Cancer Gathirua-Mwangi WG , Zhang J. European journal of cancer prevention : the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP).2014;23(2). CrossRef

- Obesity as a Risk Factor for Prostate Cancer Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of 280,199 Patients Rivera-Izquierdo M, Pérez de Rojas J, Martínez-Ruiz V, Pérez-Gómez B, Sánchez M, Khan KS , Jiménez-Moleón JJ . Cancers.2021;13(16). CrossRef

- Iraq/Afghanistan war lung injury reflects burn pits exposure Olsen T, Caruana D, Cheslack-Postava K, Szema A, Thieme J, Kiss A, Singh M, et al . Scientific Reports.2022;12(1). CrossRef

- Incidence of cancer in Iranian sulfur mustard exposed veterans: a long-term follow-up cohort study Zafarghandi MR , Soroush MR , Mahmoodi M, Naieni KH , Ardalan A, Dolatyari A, Falahati F, et al . Cancer causes & control: CCC.2013;24(1). CrossRef

- Issues related to burn pits in deployed settings Weese CB . U.S. Army Medical Department Journal.2010.

- Prostate Cancer Awareness in the Middle East Sayan M, Eren AA , Alali B, Mohammadipour S, Vahedi F, Daneshmand B, et al . International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics.2023;117(2):e433-e4.

- Awareness of prostate cancer and its screening tests in men in the Middle East: A systematic review and meta-analysis Mohamed NSA , Asfari JMO , Sambawa SMA , Aljurf RMD , Alsaygh KAA , Arafah AM . Journal of Family & Community Medicine.2025;32(1). CrossRef

- Prostate cancer screening in the Middle East and North Africa: a cross-sectional study on current practices Aynaci O, Tuac Y, Mula-Hussain L, Hammoudeh L, Obeidat S, Abu Abeelh E, Ibrahim AH , et al . JNCI cancer spectrum.2025;9(2). CrossRef

- Prostate Cancer Screening: Is it Recommended in 2024? Thwaini DA . Journal of the Faculty of Medicine Baghdad.2024;66(4). CrossRef

- Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus open radical retropubic prostatectomy: early outcomes from a randomised controlled phase 3 study Yaxley JW , Coughlin GD , Chambers SK , Occhipinti S, Samaratunga H, Zajdlewicz L, et al . The Lancet.2016;388(10049):1057-1066.

- An investigation of the risk factors associated with late toxicity after whole pelvic irradiation in patients with prostate cancer Jamil ASM , Alabedi HH , Ahmed IK , Qasim ANA . Onkologia i Radioterapia.2024;18(2).

- Cancer in the Arab world: Springer Nature; 2022. 40. Al-Worafi YM. Prostate Cancer Management in Developing Countries. Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries: Education, Practice, and Research: Springer; 2024. p. 1-19. 41. Home or Hope? The Impossible Choice for Iraqi Cancer Patients Al-Shamsi HO , Abu-Gheida IH , Iqbal F, Al-Awadhi A. 2023.

- Cancer in the Arab world: Springer Nature Al-Shamsi HO , Abu-Gheida IH , Iqbal F, Al-Awadhi A. 2022.

- Home or Hope? The Impossible Choice for Iraqi Cancer Patients 2023.

- High-Cost Cancer Treatment Across Borders in Conflict Zones: Experience of Iraqi Patients in Lebanon Skelton M, Alameddine R, Saifi O, Hammoud M, Zorkot M, Daher M, Charafeddine M, et al . JCO global oncology.2020;6. CrossRef

- International Atomic Energy A, International Agency for Research on C, World Health O. imPACT Review: Comprehensive Cancer Control in Iraq. Vienna, Austria: International Atomic Energy Agency 2021.

- Cancer incidence in the Kurdistan region of Iraq: Results of a seven-year cancer registration in Erbil and Duhok Governorates Karwan M, Abdullah OS , Amin AM , Mohamed ZA , Bestoon B, Shekha M, et al . Asian Pac j cancer prev.2022;23(2). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2025

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times