Epidemiology and Survival Outcomes of Genitourinary Cancers: A Retrospective Cohort Study from Southern Saudi Arabia

Download

Abstract

Background: Genitourinary (GU) cancers represent a significant health burden in Saudi Arabia, yet region-specific data from the southern Najran region are scarce. This study aims to characterize the epidemiology and survival outcomes of GU malignancies in this understudied population.

Patients and Methods: We conducted a retrospective single-center cohort study of 150 adults with histologically confirmed GU cancers (prostate [38.0%], bladder [28.7%], renal cell carcinoma [26.0%], testicular [7.3%]) treated at King Khaled Hospital, Najran, between 2014 and 2023. Demographic, clinical, and treatment data were analyzed. Overall survival (OS) was assessed using Kaplan-Meier methods. Multivariable Cox regression and propensity score matching were used to identify prognostic factors.

Results: The cohort was predominantly male (85.3%) with a mean age of 64.2 years. At diagnosis, 42.0% had localized disease, 18.0% had regional involvement, and 40.0% had metastatic disease. With a median follow-up of 42 months, 98 deaths were observed. The median OS for the entire cohort was 28.4 months (95% CI: 24.1–32.7). The 5-year OS rates varied significantly by subtype: prostate, 38.5%; bladder, 47.2%; renal cell carcinoma, 51.8%; and testicular cancer, 89.3%. Multivariable analysis identified metastatic disease (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 3.85; 95% CI: 2.91–5.10) and increasing age (per decade, aHR = 1.42; 95% CI: 1.21–1.67) as independent predictors of mortality. Surgical treatment was associated with a significant survival benefit (aHR = 0.52; 95% CI: 0.40–0.68), a finding confirmed in a propensity-matched analysis.

Conclusions: This first comprehensive analysis from Najran reveals a high burden of advanced GU cancers and significant survival disparities. Metastatic disease and older age are key drivers of mortality, while surgical intervention is strongly associated with improved outcomes. These findings underscore an urgent need for enhanced early detection programs and optimized treatment access in this region.

Introduction

Cancer remains a major public health challenge worldwide, with genitourinary (GU) cancers including malignancies of the prostate, bladder, kidney, and testis contributing substantially to global morbidity and mortality [1]. The incidence of these cancers has increased markedly over recent decades, with approximately 2.1 million new cases reported worldwide in 2021, reflecting a 2.5-fold rise since 1990 [2, 3]. This increase is predominantly driven by demographic changes, particularly population aging, as the number of individuals aged 65 years and older is projected to exceed 1.6 billion by 2050. Notably, over 80% of new GU cancer diagnoses occur in persons aged 60 years and above, with prostate cancer being the most prevalent within this age group [3-6].

The impact of aging on GU cancer incidence is especially pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, where limitations in healthcare infrastructure and access may exacerbate disease burden and hinder early detection [3, 5]. Regional epidemiological data from low-resource settings further highlight these challenges. For instance, a study from Nigeria reported a marked male predominance in GU cancers (male-to-female ratio of 16:1), with bladder cancer alone constituting over one- third of all GU cancer cases [7], underscoring the unique epidemiological patterns and diagnostic challenges in such regions. Similarly, mortality from GU cancers in Ethiopia increased substantially between 2000 and 2016, alongside a near doubling of prostate cancer deaths [8]. In Saudi Arabia, GU cancers account for approximately 9.2% of all malignancies and demonstrate a nearly fivefold higher incidence in men compared to women. Although the overall incidence remains lower than in Western countries where GU cancers represent up to 24% of all cancers recent national data reveal significant increases in prostate (48%) and kidney (33%) cancer incidence [9]. Despite these trends, a paucity of region-specific data, particularly from the southern Najran region, has limited the development of targeted cancer control strategies and impeded the optimization of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches [10].

This retrospective cohort study aims to address this critical gap by providing the first comprehensive analysis of the epidemiology, treatment patterns, and survival outcomes of GU cancers in patients treated at a tertiary care center in Najran. By generating region-specific insights, we seek to inform public health initiatives, guide clinical management, and ultimately improve outcomes for patients with GU malignancies in this underserved population.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at King Khaled Hospital, Najran, Saudi Arabia, a tertiary care center serving the southern region. The study included adult patients (aged ≥18 years) diagnosed with histologically confirmed genitourinary (GU) cancers specifically prostate, bladder, renal cell carcinoma (RCC), or testicular cancer between January 2014 and December 2023. Data were locked for analysis in January 2024. This design was chosen to characterize the epidemiology, treatment patterns, and survival outcomes of GU cancers in a previously understudied population.

Study Population

Inclusion Criteria

Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (1) age 18 years or older at diagnosis; (2) histopathological confirmation of a primary GU cancer (prostate, bladder, RCC, or testis); (3) receipt of at least one form of cancer-directed therapy (surgery, radiotherapy, systemic therapy, or palliative care); and (4) availability of comprehensive clinical and outcome data with a minimum follow-up duration of six months from diagnosis.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded for any of the following: (1) diagnosis of a non-GU malignancy; (2) a benign GU condition (e.g., benign prostatic hyperplasia); or (3) incomplete treatment records or follow-up of less than six months (unless due to death).

Patient Selection and Follow-Up

From an initial screening of 221 patients with suspected GU malignancies, 150 met all inclusion criteria and constituted the final study cohort. A flow diagram detailing patient selection and specific reasons for exclusion is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Patient Selection Flowchart. This diagram details the screening process for the retrospective cohort study. From an initial screening of 221 patients with suspected GU malignancies, 71 were excluded for the following reasons: 25 had benign or non-GU malignancies upon histopathological review, 20 were under 18 years of age, 15 were lost to follow-up before 6 months, and 11 had insufficient treatment or outcome data. The remaining 150 patients were included in the final survival analysis. Follow-up duration was calculated from the date of diagnosis to death or last clinical contact. Patients were censored at their last known alive date in survival analyses.

Follow-up duration was calculated from the date of histopathological diagnosis to the date of death from any cause or the last documented clinical contact. The mean follow-up time for the entire cohort was 42.3 months (standard deviation ± 18.7 months). Patients lost to follow-up before six months were excluded per our criteria. For survival analyses, patients were censored at their last known alive date.

Data Collection and Quality Assurance

Data were extracted from electronic health records using a standardized, pre-piloted checklist. Collected variables included:

• Demographics: age, sex.

• Clinical variables: smoking status (categorized as current, former [quit >1 year prior], or never; pack- year data were not routinely available), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (0–4).

• Tumor characteristics: histological subtype, primary tumor location, and stage at diagnosis. Staging was classified according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system. For cases diagnosed between 2014 and 2017, the AJCC 7th edition was used, as it was the institutional standard during those years. From 2018 onward, the AJCC 8th edition was adopted; however, to maintain uniformity and avoid stage migration bias over the entire study period (2014-2023), all tumors were restaged according to the AJCC 7th edition criteria (11).

• Treatment details: All treatments were recorded, including:

- Surgery, with intent categorized as curative (e.g., radical prostatectomy, radical cystectomy, nephrectomy, orchiectomy) or palliative (e.g., debulking, urinary diversion).

- Systemic therapy, including chemotherapy, targeted agents, immunotherapy, and hormonal therapy (for prostate cancer). The line and setting (neoadjuvant, adjuvant, metastatic) of therapy were recorded.

- Radiotherapy.

- Palliative care intent.

• Outcomes: overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival, and cause of death.

Two independent investigators performed all data extraction. Inter-rater reliability was high (Cohen’s κ > 0.90). Discrepancies, which accounted for 4.7% of variables, were resolved by consensus with a senior oncologist (third reviewer). Data on ECOG performance status were missing for 9 patients (6.0%) and were imputed using multivariate chained equations (MICE) with 20 imputations. The results of the primary analysis were consistent in a complete-case sensitivity analysis, suggesting the imputation did not introduce significant bias.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcomes were the distribution of GU cancer subtypes and overall survival (OS), defined as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause. Secondary outcomes included cancer-specific mortality (analyzed with competing risks models) and the identification of independent prognostic factors for mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation (if normally distributed) or median with interquartile range (IQR) (if skewed); normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons for continuous variables were made using ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests, and for categorical variables using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate.

Survival analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier estimators, with between-group differences assessed by the log-rank test. The restricted mean survival time (RMST) was calculated at 60 months, a clinically relevant timepoint for evaluating mid-term survival in GU cancers. For cancer-specific mortality, Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard models were used to account for competing risks of non-cancer death.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify independent predictors of all-cause mortality. The model was adjusted for pre-specified covariates: age, cancer stage, ECOG performance status, treatment modality (surgical vs. non-surgical), and smoking status. The proportional hazards assumption was verified using Schoenfeld residuals, and the absence of multicollinearity was confirmed by variance inflation factors (all VIF < 2.0). Given that all tested predictors were pre-specified based on clinical relevance, no additional correction for multiple testing (e.g., Bonferroni) was applied. Model stability was assessed; the number of events (98 deaths) was adequate for the number of covariates included.

To address potential confounding by indication in the assessment of the surgical treatment effect, we performed propensity score matching (PSM). A logistic regression model was used to generate a propensity score for receiving surgery, incorporating the following confounders: age, cancer type, stage at diagnosis, ECOG status, and comorbidities. We then performed 1:1 nearest- neighbor matching without replacement, using a caliper width of 0.2 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score. Balance after matching was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMD < 0.1 for all variables indicated good balance). The association between surgery and survival was then re-evaluated in the matched cohort using Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses. To address immortal time bias, a landmark analysis at 90 days post-diagnosis was conducted as a sensitivity analysis.

All analyses were performed using Python version 3.9 (lifelines, scikit-learn packages) and R version 4.3.1 (survival, cmprsk, MatchIt packages). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p value < 0.05.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of King Khaled Hospital, Najran (IRB Log: 2025-41A; Approval Date: April 15, 2025). The IRB approval was obtained retrospectively after data lock to ensure formal ethical oversight and compliance with institutional policy for this analysis of pre-existing, de-identified data. The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of the study. The study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patient identifiers were removed and data were encrypted to ensure confidentiality.

Results

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics A total of 150 patients with histologically confirmed genitourinary (GU) cancers were included in the analysis. The cohort was predominantly male (85.3%, n = 128) with a mean age of 64.2 ± 14.3 years. The distribution of cancer types was as follows: prostate cancer (38.0%, n = 57), bladder cancer (28.7%, n = 43), renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (26.0%, n = 39), and testicular cancer (7.3%, n = 11) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Subcategory | n (%) or Mean ± SD | Statistical Test (p-value) |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | Overall | 64.2 ± 14.3 | One-way ANOVA (p < 0.001) a |

| Prostate cancer | 72.0 ± 9.1 | ||

| Bladder cancer | 67.0 ± 12.4 | ||

| Renal cell carcinoma | 58.0 ± 14.3 | ||

| Testicular cancer | 32.0 ± 10.5 | ||

| Gender | Male | 128 (85.3) | Pearson's chi-square (p = 0.08) b |

| Female | 22 (14.7) | ||

| Current Smoking | Yes | 56 (37.3) | Pearson's chi-square (p = 0.03) b |

| No | 94 (62.7) | ||

| Cancer Type | Prostate cancer | 57 (38.0) | — c |

| Bladder cancer | 43 (28.7) | ||

| Renal cell carcinoma | 39 (26.0) | ||

| Testicular cancer | 11 (7.3) | ||

| Presenting Symptoms | Pain | 63 (42.0) | Pearson's chi-square (p = 0.02) b |

| Hematuria | 58 (38.7) | ||

| Palpable mass | 23 (15.3) | ||

| Comorbidities d | Diabetes mellitus | 57 (38.0) | Pearson's chi-square (p = 0.15) b |

| Hypertension | 51 (34.0) | ||

| Stage at Diagnosis | Localized | 63 (42.0) | Pearson's chi-square (p < 0.001) b |

| Regional (lymph nodes) | 27 (18.0) | ||

| Metastatic | 60 (40.0) |

Notes: SD = standard deviation; ANOVA = analysis of variance. Footnotes: ᵃ One-way ANOVA was used to compare the means of a continuous, normally distributed variable (age) across more than two independent groups (cancer types). ᵇ Pearson’s chi-square test was used to assess for associations between two categorical variables (the characteristic and cancer type). ᶜ Cancer type is the primary grouping variable; no statistical comparison was made. ᵈ Comorbidity data were missing for 6 patients; percentages are calculated from the total cohort (N=150) for consistency, but the statistical test was performed on available data.

Age differed significantly between cancer subtypes (ANOVA, p < 0.001), with testicular cancer patients being the youngest (mean 32 ± 10.5 years) and prostate cancer patients the oldest (mean 72 ± 9.1 years). Presenting symptoms included pain (42.0%, n = 63), hematuria (38.7%, n = 58), and palpable mass (15.3%, n = 23). Comorbidities were common, with diabetes mellitus present in 38.0% (n = 57) and hypertension in 34.0% (n = 51) of patients. Six patients had undocumented comorbidities and were excluded from comorbidity analyses. At diagnosis, 42.0% (n = 63) had localized disease, 18.0% (n = 27) had regional lymph node involvement, and 40.0% (n = 60) presented with metastatic disease (Table 1).

Treatment Modalities

Surgical intervention was the most frequently administered treatment, received by 58.0% (n = 87) of patients. Surgical procedures were categorized as curative- intent (e.g., radical prostatectomy, radical orchiectomy, radical cystectomy, nephrectomy) and were distinct from palliative/debulking procedures, which were categorized under palliative care. Other treatment modalities included chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, hormonal therapy (for prostate cancer), and palliative care, with distribution varying by cancer subtype (See Supplemental Tables S1-3 for a detailed breakdown).

Survival Outcomes

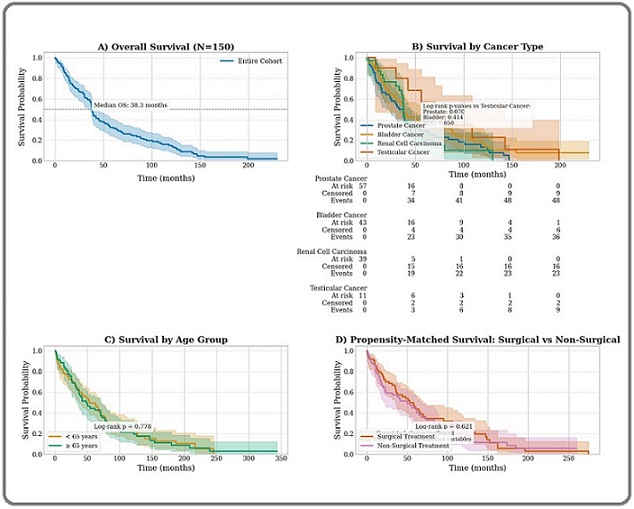

The median overall survival (OS) for the entire cohort was 28.4 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 24.1–32.7) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Survival Analysis of GU Cancer Patients. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve showing overall survival for the entire cohort (N = 150). Median overall survival was 28.4 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 24.1–32.7). Tick marks denote censored observations. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by cancer type (prostate, bladder, renal cell carcinoma [RCC], testicular). The log-rank test indicated significant differences among subtypes (p < 0.001). Shaded areas represent 95% CIs. (C) Kaplan-Meier curves comparing overall survival between patients aged < 65 years (n = 87) and those ≥65 years (n = 63). Younger patients had significantly better survival (log-rank p < 0.001). The dashed vertical line marks the median follow-up of 42 months. (D) Kaplan-Meier curves from the propensity score-matched analysis comparing patients who underwent surgical treatment (n = 63) with those who did not (n = 63). Surgical treatment was associated with significantly improved survival (log-rank p = 0.012). Covariate balance was confirmed with standardized mean differences <0.1 for all matched variables.

With a median follow-up of 42 months, 98 deaths were observed. Survival differed significantly by cancer subtype (log-rank test, p < 0.001) (Figure 2B). The 5-year OS rates were 38.5% (95% CI, 30.1–46.9) for prostate cancer, 47.2% (38.6–55.8) for bladder cancer, 51.8% (43.0–60.6) for RCC, and 89.3% (82.4–96.2) for testicular cancer (Table 2).

| Cancer Type | Median OS (months, 95% CI) | Number of Deaths / N | 5-Year OS % (95% CI) | Log-rank p-valueᵃ |

| All GU Cancers | 28.4 (24.1–32.7) | 98 / 150 | 42.1 (35.7–48.5) | — |

| Prostate Cancer | 26.1 (20.3–31.9) | 38 / 57 | 38.5 (30.1–46.9) | 0.003 * |

| Bladder Cancer | 31.2 (24.8–37.6) | 25 / 43 | 47.2 (38.6–55.8) | 0.08 |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 22.5 (16.4–28.6) | 19 / 39 | 51.8 (43.0–60.6) | <0.001 * |

| Testicular Cancer | Not reached | 2 / 11 | 89.3 (82.4–96.2) | Reference |

Notes: OS = overall survival; CI = confidence interval. Footnotes: ᵃ The log-rank test compares the survival distribution of each group against the reference group (testicular cancer). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Age was a significant determinant of survival, with patients younger than 65 years (n = 87) exhibiting a 5-year OS of 58.1% (95% CI, 49.3–66.9) compared to 31.7% (95% CI, 23.5–39.9) in those aged 65 years or older (n = 63) (log-rank p < 0.001) (Figure 2C).

Metastatic disease at diagnosis was associated with significantly worse survival outcomes. Median OS was 18.2 months (95% CI, 14.1–22.3) for metastatic patients (n = 60) versus 45.6 months (95% CI, 38.9–52.3) for those with localized or regional disease (n = 90) (log-rank p < 0.001).

Multivariable Analysis of Mortality Predictors

In multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression (Table 3), metastatic disease at diagnosis was the strongest predictor of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 3.85; 95% CI, 2.91–5.10; p < 0.001).

| Variable | aHR (95% CI) | p-value | Wald χ 2 |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 1.42 (1.21–1.67) | <0.001 | 18.7 |

| Metastatic at diagnosis | 3.85 (2.91–5.10) | <0.001 | 42.3 |

| Surgical treatment (yes vs no) | 0.52 (0.40–0.68) | <0.001 | 15.2 |

| Current smoker (vs never) | 1.67 (1.20–2.32) | 0.002 | 9.4 |

| Hypertension (yes vs no) | 1.21 (0.95–1.54) | 0.12 | 2.4 |

Notes: aHR = adjusted hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval. Model fit: Concordance = 0.71; Likelihood ratio test χ2 = 58.3 (df = 5, p < 0.001).

Increasing age per 10-year increment was also associated with higher mortality risk (aHR = 1.42; 95% CI, 1.21–1.67; p < 0.001). Surgical treatment conferred a significant survival benefit (aHR = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.40–0.68; p < 0.001). Current smoking status was independently associated with increased mortality (aHR = 1.67; 95% CI, 1.20–2.32; p = 0.002), while hypertension did not reach statistical significance (aHR = 1.21; 95% CI, 0.95–1.54; p = 0.12).

Propensity-Matched Survival Analysis

To address potential confounding in the assessment of the surgical treatment effect, we performed propensity score matching. From the original cohort of 87 surgical patients and 63 non-surgical patients, we matched 63 surgical patients 1:1 with 63 non-surgical patients based on age, cancer stage, ECOG performance status, and comorbidities, without replacement. After matching, surgical intervention remained associated with improved survival. Median OS was 34.1 months for the surgical group versus 22.8 months for the non-surgical group (log-rank p = 0.012). Covariate balance was confirmed with standardized mean differences below 0.1 for all matched variables (Figure 2D). An analysis of regional cancer registry data from 2000 to 2020 revealed a significant and increasing burden of GU cancers in the Najran region, with an overall age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) of 10.2 per 100,000, a pronounced male predominance (male-to-female ratio: 4.3:1), and a significant annual increase in incidence (APC +1.8%; p < 0.05) (Table 4).

| Category | Crude Incidence Rate (CIR) | ASIR (WHO Standard) | Male:Female Ratio | Annual Percent Change (APC) |

| Overall | 12.4 | 10.2 | 4.3:1 | +1.8% * |

| Males | 19.8 | 16.3 | — | +1.5% * |

| Females | 4.6 | 3.8 | — | 0.90% |

Notes: ASIR = age-standardized incidence rate (per 100,000 person-years); APC = annual percent change. •p < 0.05 for a significant trend. Data source: Saudi National Cancer Registry, Najran branch.

Discussion

This comprehensive analysis provides the first detailed characterization of the epidemiology, treatment patterns, and survival outcomes of genitourinary (GU) cancers in the Najran region of southern Saudi Arabia. Our findings, derived from a retrospective cohort of 150 patients, highlight a pronounced male predominance and a high incidence of advanced-stage disease at diagnosis, with nearly 40% of patients presenting with metastases. These patterns mirror national data from Saudi Arabia and trends observed in neighboring Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) countries, underscoring persistent regional challenges in early detection [12-15]. The overall 5-year survival rate was 42.1%, with significant disparities by cancer type, strongly influenced by metastatic burden, age, and access to surgical intervention.

The observed 5-year survival rates prostate cancer (38.5%), bladder cancer (47.2%), renal cell carcinoma (RCC; 51.8%), and testicular cancer (89.3%) are consistent with recent reports from the Saudi Cancer Registry [16]. The superior survival for testicular cancer aligns with global trends, reflecting the high efficacy of platinum-based chemotherapy and the young age at diagnosis [17]. However, our rates are slightly lower than those reported in some high-resource Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states like Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, where 5-year survival for prostate and bladder cancers can exceed 50-60% % [18-20]. This discrepancy may be attributed to variations in stage at presentation, access to multidisciplinary care, and the availability of newer systemic therapies. In contrast, our outcomes appear more favorable than those reported in resource-constrained settings in Africa, reinforcing the role of healthcare infrastructure [7, 8, 21]. Our data also aligns with patterns seen in other Middle Eastern populations; for instance, studies from Northern and Southern Iran found bladder cancer to be a significant burden with a male predominance [22, 23], similar to our cohort , while long-term data from Izmir, Turkey, shows comparable temporal trends in GU cancer incidence [22].

Consistent with global literature, our multivariable analysis identified metastasis at diagnosis (aHR 3.85, p < 0.001) and advancing age (aHR 1.42 per decade, p < 0.001) as the strongest independent predictors of mortality [24, 25]. Conversely, surgical intervention was independently associated with a significant reduction in mortality risk (aHR 0.52, p < 0.001), a finding robust to propensity score matching and a landmark analysis to mitigate immortal time bias. This reinforces the established benefit of curative-intent surgery for localized GU malignancies, as demonstrated in studies of radical prostatectomy and nephrectomy [26, 27]. It is important to note that this observed association is likely influenced by confounding by indication, as healthier patients with less advanced disease are selected for surgery. Furthermore, for prostate cancer, potential lead-time bias resulting from variable PSA testing practices could artificially inflate survival estimates in screened populations, though this is less likely to be a major factor in our region where organized screening is not prevalent. The rising incidence of GU cancers in Saudi Arabia, also noted in national surveys from Iran [28], underscores the urgency of developing effective early detection strategies that are tailored to the region’s specific needs and resource constraints.

Our study also reveals notable gender-based differences. Females accounted for 20.9% of bladder cancer and 35.9% of RCC cases, consistent with global patterns where these cancers are more common in males but not exclusively so [17, 29]. Importantly, 5-year survival rates for bladder cancer and RCC were comparable between genders, supporting existing evidence that outcomes are driven more by stage and treatment than by sex itself [30].

Implications for Practice and Public Health

The findings from this cohort underscore several critical avenues for intervention within the healthcare system of southern Saudi Arabia. First, the high proportion of patients presenting with metastatic disease signals an urgent need for enhanced public awareness campaigns focused on the early symptoms of genitourinary cancers (e.g., hematuria, urinary obstruction, and palpable masses), particularly targeting high-risk groups such as older males [31]. Second, primary care protocols should be strengthened to facilitate timely urology referrals for patients with these warning signs, thereby reducing diagnostic delays. Third, given the strong association between surgical intervention and improved survival, ensuring equitable and rapid access to surgical oncology expertise is paramount. This may require strategic resource allocation and the development of standardized, multidisciplinary care pathways within the region [32]. Finally, the independent risk associated with current smoking reinforces the necessity of integrating robust, culturally adapted smoking cessation programs into both primary care and oncology practice. To sustainably address these challenges and monitor progress, the establishment of a comprehensive, region-wide cancer registry is indispensable for guiding evidence-based public health strategy and resource distribution [33].

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations inherent to its retrospective, single-center design, which may introduce selection and information biases. By including only patients who received cancer-directed therapy, we may have excluded those with advanced disease deemed unfit for treatment, potentially skewing survival estimates upwards. The relatively small sample size, particularly for testicular cancer, limited the power of some subgroup analyses. While we adjusted for key confounders, unmeasured factors such as socioeconomic status, detailed treatment protocols (e.g., specific chemotherapy regimens), and molecular profiles could contribute to residual confounding. The use of the AJCC 7th edition, while justified for consistency, may limit direct comparability with studies using the 8th edition. Finally, the absence of data on recurrence or patient-reported outcomes (e.g., quality of life) limits the scope of our analysis. Future research should prioritize prospective, multicenter designs that incorporate molecular profiling and longer-term longitudinal data to validate these findings and advance personalized medicine for GU cancers in the MENA region.

In conclusion, this study provides foundational insights into the burden of GU cancers in southern Saudi Arabia. As the first comprehensive analysis from the Najran region, our findings reveal a significant male predominance, a high rate of advanced-stage presentation, and substantial survival disparities across cancer subtypes, strongly influenced by metastatic burden and tumor histology. Surgical intervention was independently associated with improved survival, highlighting the critical importance of timely diagnosis and access to effective treatment. These findings underscore several urgent needs: enhanced public awareness of GU cancer symptoms, the implementation of targeted early detection initiatives, and the optimization of clinical care pathways to reduce delays. The prognostic significance of metastatic disease, age, and smoking status supports the adoption of individualized risk stratification to guide clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgments

Statement of Transparency and Principals:

• Author declares no conflict of interest

• Study was approved by Research Ethic Committee of author affiliated Institute.

• Study’s data is available upon a reasonable request.

• All authors have contributed to implementation of this research.

References

- Secular trends of morbidity and mortality of prostate, bladder, and kidney cancers in China, 1990 to 2019 and their predictions to 2030 Huang Q, Zi H, Luo L, Li X, Zhu C, Zeng X. BMC Cancer.2022;22(1). CrossRef

- Cancer Statistics, 2021 Siegel RL , Miller KD , Fuchs HE , Jemal A. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.2021;71(1). CrossRef

- Global burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia, urinary tract infections, urolithiasis, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, and prostate cancer from 1990 to 2021 Zi H, Liu M, Luo L, Huang Q, Luo P, Luan H, Huang J, et al . Military Medical Research.2024;11(1). CrossRef

- Trends and risk factors of global incidence, mortality, and disability of genitourinary cancers from 1990 to 2019: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 Tian Y, Yang J, Hu J, Ding R, Ye D, Shang J. Frontiers in Public Health.2023;11. CrossRef

- Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer in the Arab World: 2019 Global Burden of Disease Data Al Saidi I, Mohamedabugroon A, Sawalha A, Sultan I. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.2022;23(9). CrossRef

- Global Burden of Urologic Cancers, 1990–2013 Dy GW , Gore JL , Forouzanfar MH , Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C. European Urology.2017;71(3). CrossRef

- Review of urological cancers in Damaturu, Nigeria Tela UN , Adamu AI , Abubakar BM , Abubakar A, Dogo HM . International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences.2021;9(2). CrossRef

- Pattern of genitourinary tract cancers in southern Ethiopia: A retrospective document review Gebretsadik A, Bogale N, Dulla D. Ethiopian Journal of Medical and Health Sciences.2023;3(2). CrossRef

- Genito-urinary cancer in Saudi Arabia Abomelha MS . Saudi Medical Journal.2004;25(5). CrossRef

- Trends of genitourinary cancer among Saudis Abomelha MS . Arab Journal of Urology.2011;9(3). CrossRef

- The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual and the Future of TNM Edge SB , Compton CC . Annals of Surgical Oncology.2010;17(6). CrossRef

- The incidence rate of prostate cancer in Saudi Arabia: an observational descriptive epidemiological analysis of data from the Saudi Cancer Registry 2001-2008 Alghamidi IG , Hussain II , Alghamdi MS , El-Sheemy MA . Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy.2014;7(1). CrossRef

- Arab world’s impact on bladder cancer research and opportunities for growth: A bibliometric review study Saleh M, Raffoul P, Akil A, Bassil P, Salameh P. Medicine.2024;103(12). CrossRef

- Genitourinary cancers in the Arab world: A bibliometric study Ibrahim S, Farhat T, Baalbaki R, Aoun M, Toumieh G, Kaddoura M, Jaber L, Taher AT , Abdul-Sater Z. Frontiers in Urology.2022;2. CrossRef

- Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer in 2023: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors Jubber I, Ong S, Bukavina L, Black PC , Compérat E, Kamat AM , Kiemeney L, et al . European Urology.2023;84(2). CrossRef

- Saudi Cancer Registry. Cancer Incidence Report Saudi Arabia 2020. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Ministry of Health. Available from: https://nhic.gov.sa/eServices/Documents/E%20SCR%20final%206%20NOV.pdf, accessed 07 May 2025. Available from. .

- Global cancer statistics Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM , Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2011;61(2). CrossRef

- Incidence of cancer in Gulf Cooperation Council countries, 1998-2001 Al-Hamdan N., Ravichandran K., Al-Sayyad J., Al-Lawati J., Khazal Z., Al-Khateeb F., Abdulwahab A., Al-Asfour A.. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal = La Revue De Sante De La Mediterranee Orientale = Al-Majallah Al-Sihhiyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassit.2009;15(3). CrossRef

- Kuwait National Cancer Registry. Cancer Incidence Report Kuwait 2015. Kuwait City: Ministry of Health, Kuwait. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.kw/EN/Pages/Statistics.aspx (accessed 07 May 2025). Available from .

- United Arab Emirates National Cancer Registry. Cancer Incidence Report UAE 2017. Abu Dhabi: Ministry of Health and Prevention. Available from: https://mohap.gov.ae/en/Pages/Statistics.aspx (accessed 07 May 2025). .

- Cancer Incidence in Egypt: Results of the National Population-Based Cancer Registry Program Ibrahim AS , Khaled JM , Mikhail NN , Baraka H, Kamel H. Journal of Cancer Epidemiology.2014;2014. CrossRef

- Epidemiologic and Socioeconomic Status of Bladder Cancer in Mazandaran province, Northern Iran Ahmadi M, Ranjbaran H, Amiri MM , Nozari J, Mirzajani MR , Azadbakht M, Hosseinimehr SJ . Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.2012;13(10). CrossRef

- Epidemiologic status of bladder cancer in Shiraz, southern Iran Salehi A, Khezri A, Malekmakan L, Aminsharifi A. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2011;12(5). CrossRef

- A Genitourinary Cancer-specific Scoring System for the Prediction of Survival in Patients with Bone Metastasis: A Retrospective Analysis of Prostate Cancer, Renal Cell Carcinoma, and Urothelial Carcinoma Owari T, Miyake M, Nakai Y, Morizawa Y, Hori S, Anai S, et al . Anticancer Research.2018;38(5). CrossRef

- Disparities and Trends in Genitourinary Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the USA Schafer EJ , Jemal A, Wiese D, Sung H, Kratzer TB , Islami F, Dahut WL , Knudsen KE . European Urology.2023;84(1). CrossRef

- The role of surgery in the management of metastatic kidney cancer: an evidence-based collaborative review Mir MC , Matin SF , Bex A, Spiess PE , Thompson R , Grob B, Van Poppel H. Minerva Urology and Nephrology.2018;70(2). CrossRef

- Comparison of mortality outcomes after radical prostatectomy versus radiotherapy in patients with localized prostate cancer: A population‐based analysis Abdollah F, Schmitges J, Sun M, Jeldres C, Tian Z, Briganti A, Shariat SF , Perrotte P, Montorsi F, Karakiewicz PI . International Journal of Urology.2012;19(9). CrossRef

- Incidence Trend and Epidemiology of Common Cancers in the Center of Iran Rafiemanesh H, Rajaei-Behbahani N, Khani Y, Hosseini S, Pournamdar Z, Mohammadian- Hafshejani A, Soltani S, Hosseini SA , Khazaei S, Salehiniya H. Global Journal of Health Science.2015;8(3). CrossRef

- Gender differences in incidence and outcomes of urothelial and kidney cancer Lucca I, Klatte T, Fajkovic H, De Martino M, Shariat SF . Nature Reviews Urology.2015;12(10). CrossRef

- Sex differences in metastatic surgery following diagnosis of synchronous metastatic colorectal cancer Ljunggren M, Weibull CE , Palmer G, Osterlund E, Glimelius B, Martling A, Nordenvall C. International Journal of Cancer.2023;152(3). CrossRef

- Towards a comprehensive cancer control policy in Saudi Arabia Alessy SA , Al-Zahrani A, Alhomoud S, Alaskar A, Haoudi A, Alkheilewi MA , Alhamali M, Alsharm AA , Asiri M, Alqahtani SA . The Lancet Oncology.2025;26(7). CrossRef

- Cancer Incidence in Saudi Arabia: 2012 Data from the Saudi Cancer Registry Bazarbashi S, Al-Eid H, Minguet J. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.2017;18(9). CrossRef

- Causative relationship between diabetes mellitus and breast cancer in various regions of Saudi Arabia: an overview Arif JM , Al-Saif AM , Al-Karrawi MA , Al-Sagair OA . Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2011;12(3). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2025

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times