Weekly Procalcitonin Kinetics as an Early Biomarker of Treatment Response in Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Undergoing Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Study

Download

Abstract

Background: Early identification of response during concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cCRT) for stage III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) could critically inform clinical decision-making, particularly regarding surgical candidacy, modification or completion of therapy, and optimal integration with immunotherapies. This prospective study evaluates weekly serum procalcitonin (PCT) kinetics as a biomarker of treatment response in stage III NSCLC receiving cCRT, analyzing the potential to guide individualized care pathways.

Methods: In this multicenter prospective observational study, adults aged 18–65 years with stage III NSCLC eligible for upfront concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cCRT) were enrolled. Key exclusions were elevated baseline procalcitonin (PCT > 0.1 ng/mL), active infection at baseline or during cCRT, autoimmune disease, incomplete radiotherapy, or ECOG 3–4. Serum PCT was measured at baseline and weekly during radiotherapy. Tumor response was assessed 4–6 weeks post‑cCRT by RECIST v1.1. PCT trajectories were analyzed using mixed‑design repeated‑measures ANOVA (Time × Response), with non‑parametric alternatives as needed. Logistic regression evaluated baseline and early PCT changes as predictors of response, and ROC analysis determined AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and optimal cut‑offs. Analyses were performed in SPSS v20; p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results: Of 79 screened, 73 were evaluable (5 CR, 24 PR, 27 SD, 17 PD). Responders (n=29) exhibited a consistent transient PCT peak at week 2 or 3, followed by a progressive decline. Non-responders (n=44) lacked this pattern, showing rather stable or irregular pattern of PCT levels. Repeated measures LMEM demonstrated a significant time × response effect (p<0.001). Logistic regression incorporating early PCT rise predicted response (AUC=0.84). Integration of PCT kinetics could support decisions to proceed to surgery or continue radiotherapy without interruption, obviating delays for radiologic confirmation.

Conclusions: This is the first prospective report of PCT kinetics as a biomarker of cCRT response in lung cancer. A characteristic early, transient PCT rise followed by decline is associated with treatment response. Dynamic PCT monitoring can enable real‑time, individualized decision‑making, including timing for surgical evaluation and potential for mid‑treatment immunotherapeutic intensification.

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide; approximately one-third of patients present with stage III, potentially curable disease [1, 2]. The current standard-of-care for stage III disease encompasses multimodality strategies, with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cCRT) securing better outcomes than sequential approaches [2]. Recent advances such as consolidation immunotherapy with anti‑PD‑L1 agents (e.g., durvalumab, as per the PACIFIC trial) have improved both progression-free and overall survival in unresectable stage III NSCLC [3]. However, substantial heterogeneity persists in treatment trajectories and outcomes, and many patients are not cured. Traditionally, assessment of therapeutic response during cCRT has relied on interval imaging (typically after delivery of 45 Gy of radiation), which can lag behind dynamic tumor biology. Such delays can impede timely decisions regarding surgical resectability after induction therapy, unnecessary treatment continuation in non-responders, or the appropriate integration and sequencing of adjunct modalities [4]. There remains a critical need for reliable, minimally invasive biomarkers capable of early response prediction to enable prompt and individualized intervention [5].

Procalcitonin (PCT) is a 116-amino acid precursor of calcitonin, physiologically produced by parafollicular C-cells in the thyroid but upregulated systemically in response to pro‑inflammatory cytokines and bacterial infection [6]. In oncology, PCT has emerged primarily as a marker to distinguish bacterial from non-infectious systemic inflammatory response, but recent evidence suggests that PCT may be elevated in advanced malignancies (including NSCLC) even in the absence of infection, correlating with tumor burden and prognosis [7, 8]. Elevated PCT at baseline has been associated with inferior survival and poor checkpoint inhibitor response in advanced NSCLC [8, 9].

Despite these findings, the dynamic course of PCT during definitive cCRT has not been prospectively evaluated in lung cancer. No prior studies have addressed whether temporal changes-rather than single time-point measures-could serve as a surrogate for tumor response, guide real-time treatment adaptation, or inform timing for optimal integration with surgery or immunotherapies [10]. The authors hypothesized that tissue damage due to radiation therapy could lead to a rise in procalcitonin level which may reflect the destruction of tumor cells and predict response to treatment.

This prospective, multicenter observational study aimed to characterize weekly PCT kinetics in stage III NSCLC patients undergoing cCRT and to correlate PCT trajectory patterns with radiologic response. This will evaluate the predictive value of baseline and early on-treatment PCT changes, and assess the potential utility of PCT as an actionable biomarker for mid-treatment decision-making.

Materials and Methods

This multicenter, prospective observational cohort study was conducted from June 2023 to May 2025 at Menoufia University, Ain Shams University, and South Egypt Cancer Institute. The protocol was approved by the Menoufia University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee and adopted at participating centers per the supreme council of universities regulations. All participants provided written informed consent. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. No external funding was received.

Eligible participants were adults aged 18–65 years with histologically confirmed, previously untreated non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) of any histologic subtype and clinical stage III disease per AJCC 8th edition. Required baseline status included ECOG performance 0–2, serum procalcitonin (PCT) within institutional normal reference range (≤0.1 ng/mL), and adequate hematologic, renal, and hepatic function per local laboratory thresholds. Exclusion criteria were ECOG 3–4, baseline PCT >0.1 ng/ mL, clinical/laboratory/radiologic evidence suggestive of bacterial or fungal infection at baseline, active autoimmune disease, receipt of <95% of planned radiotherapy dose, development of any confirmed infection during cCRT, or concurrent enrollment in another interventional trial. Eligibility was confirmed prior to enrollment.

Participants received institutional standard-of-care concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cCRT): platinum‑doublet chemotherapy (cisplatin or carboplatin with etoposide, paclitaxel, or vinorelbine) given concurrently with conventionally fractionated thoracic radiotherapy (60–66 Gy in 2 Gy fractions over 6–7 weeks). No patients received upfront immune checkpoint inhibitors. Supportive care (antiemetics, growth factors) followed local guidelines. Prophylactic systemic antibiotics were not used unless clinically indicated.

Peripheral venous blood for serum PCT was collected at baseline (pre cCRT) and weekly during radiotherapy. PCT was measured using a standardized electrochemiluminescence immunoassay per manufacturer instructions with internal quality control to ensure inter-assay consistency. Weekly clinical assessments recorded vital signs and a structured symptom checklist for infectious symptoms. Additional labs and imaging were performed as clinically indicated. Fever >38.0 °C, new focal infectious signs, or new pulmonary infiltrates prompted infectious disease review. Confirmed infections per protocol criteria led to exclusion from further primary cohort analyses; data collected up to the infection date were retained as described in the Statistical analysis section.

Tumor response and outcome definitions

Radiologic tumor response was assessed 4–6 weeks after cCRT completion by contrast‑enhanced chest CT (± abdomen) and scored by RECIST 1.1 by reviewers blinded to PCT results. Primary and secondary outcomes were prespecified in the protocol:

• Primary outcome: change in serum PCT from baseline To end of treatment (principal comparison), with intermediate weekly trajectories described; primary prespecified comparison is between responders and non-responders.

• Key secondary outcomes: radiologic response category at 4–6 weeks (CR/PR = responders; SD/PD = nonresponders), absolute weekly PCT values, responder status at 4–6 weeks (binary), time-to-progression from enrollment to radiographic progression or death, and safety endpoints including incidence of clinically significant infections and treatment related adverse events.

Sample size justification

A priori sample‑size calculation targeted detection of a between‑group mean difference in PCT change Δ = 0.50 ng/mL with pooled SD σ = 0.80 ng/mL, two‑sided α = 0.05 and 80% power using a two‑sample comparison of means:

This produced n ≈ 21 per group. Allowing 15% attrition or exclusion related to intercurrent infections or non-evaluable data increased the per-group target to 25 (total planned N = 50). Enrollment exceeded the planned target; after exclusion of six patients with confirmed infections during cCRT the final analytic cohort comprised 73 patients.

Analysis populations and handling of infection-related exclusions

• ITT (primary) population: all enrolled participants meeting inclusion criteria with ≥1 post baseline PCT measurement; analyses by observed radiologic response category (responder vs nonresponder at 4–6 weeks).

• Per‑protocol (PP) population: ITT subset excluding predefined major protocol violations (including receipt of <95% planned radiotherapy).

• Complete‑case population: participants with nomissing values for the variables in a given analysis.

• Infection handling: for longitudinal PCT analyses, observations obtained after confirmed infection or after initiation of systemic antibiotics are excluded from the primary analysis to avoid confounding by infectious PCT elevation; pre infection values are retained. Sensitivity analyses include (1) censoring all data at the infection date (removing post infection observations), and (2) joint models linking longitudinal PCT and time to infection to evaluate informative dropout.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are summarized as mean ± SD or median (IQR) depending on distribution; categorical data are counts and percentages. All tests are two sided. The primary analysis significance threshold is p < 0.05. Effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals are reported for all primary inferential results.

Longitudinal PCT trajectories were analysed using linear mixed effects models (restricted maximum likelihood). The primary model included fixed effects for time (categorical weekly visits), response group (responder vs nonresponder), and the time × response interaction, and a random intercept for participant; random slopes for time were added when supported by likelihood ratio tests. Model selection for covariance structure used Akaike information criterion. Primary inference derives from the time × response interaction with adjusted estimated marginal means and 95% CIs reported. Effect‑size metrics: marginal R² (R²m) and conditional R² (R²c) using Nakagawa’s method quantify variance explained by fixed effects and the full model, respectively; partial eta‑squared (η²p) is reported for ANOVA style summaries of the interaction where presented. Bootstrap (1,000 resamples) is used to produce 95% CIs for R² and η²p when feasible. Residual diagnostics (QQ plots, residual vs fitted) and heteroscedasticity checks are performed. If major assumption violations occur, results are confirmed using (1) a mixed model with robust sandwich variance estimators and (2) a rank based mixed model (nonparametric repeated-measures approach).

Secondary analyses

• Repeated continuous secondary outcomes use the same mixed effects framework. Reported effect sizes include R²m/R²c and η²p with 95% CIs.

• Time to event endpoints use Kaplan–Meier estimators and Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for prespecified covariates; proportional hazards are checked with Schoenfeld residuals. Effect sizes reported include hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs and Harrell’s C index with 95% CI.

• Binary outcomes (responder status) are analyzed with multivariable logistic regression adjusted for prespecified covariates; effect sizes include adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs and Nagelkerke R². Model discrimination (AUC) and calibration (Hosmer–Lemeshow, calibration plots) are reported.

Predictive modelling and incremental value

Multivariable logistic regression models assessed associations of baseline PCT and early ΔPCT with radiologic response, adjusted for age, sex, baseline ECOG, and histology (squamous vs non squamous). Reported metrics include adjusted ORs, Nagelkerke R², change in R² and AUC when adding PCT variables (AUC change 95% CIs by DeLong’s method), and likelihood ratio tests for incremental fit.

ROC analyses

ROC curves estimated AUC with 95% CIs for candidate predictors (baseline PCT, ΔPCT at prespecified time points). Optimal cutoffs were selected using Youden’s index; sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value with 95% CIs are reported.

Missing data strategy and sensitivity analyses

Patterns and mechanisms of missingness are inspected and classified (MCAR, MAR, or plausibly MNAR). Primary approach for longitudinal mixed models uses available case estimation under the MAR assumption (mixed models use all nonmissing observations). Sensitivity strategies:

1. Multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) with m = 20 imputations for outcomes and covariates plausibly MAR; imputation models include outcome history, baseline covariates (age, sex, ECOG, histology), auxiliary predictors of missingness, and infection status prior to censoring; pooled estimates use Rubin’s rules.

2. Complete case analysis.

3. Worst best case and pattern mixture models when MNAR is suspected.

All analyses explicitly report numbers of observations/ participants included and dates of censoring or exclusion.

Outliers and diagnostics

Outliers identified by standardized residuals (|z| > 3) and influence measures (Cook’s distance > 4/n) are examined; analyses are presented with and without influential observations. Multicollinearity is assessed via variance inflation factors. Robust or nonparametric methods are used when diagnostics indicate serious violations of model assumptions.

Multiplicity

Primary hypothesis testing for the primary endpoint is performed at α = 0.05 without multiplicity adjustment. For families of secondary endpoints and multiple time point comparisons, the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate procedure is applied within endpoint families. A prespecified hierarchical testing sequence was used for predefined key secondary endpoints where indicated.

Handling of patients excluded for infection

Patients with confirmed infection during cCRT were excluded from the primary longitudinal analysis after the infection date; pre infection data were retained. Sensitivity analyses include (1) censoring at infection, and (2) joint longitudinal time to event models treating infection as an informative event. The number of excluded patients and timing of exclusions are reported.

Software and reproducibility

Descriptive statistics and initial comparisons used IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Primary longitudinal models, multiple imputation, effect size calculations, bootstrapped CIs, ROC analyses, and plots used R version 4.2.2 with key packages lme4, nlme, MuMIn (R²m/R²c), effectsize (η²p, Cohen’s d), mice, pROC, rms, sandwich, and boot. Effect sizes reported include η²p, R²m/R²c, Nagelkerke R², Cohen’s d (where appropriate), AUC, and Harrell’s C index with 95% CIs. Analysis scripts and the deidentified analytic dataset are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request to support reproducibility.

Safety oversight and deviations

Safety events were reviewed by local clinical teams at prespecified intervals. No formal interim efficacy analyses were planned. Any deviations from the prespecified protocol or analysis plan are documented in the manuscript with rationale and timing.

Results

Seventy three patients met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis: 29 responders (CR/PR) and 44 non responders (SD/PD). Baseline demographic, clinical, and molecular characteristics were well balanced between groups (Table 1).

| Parameter | Responders (n=29) | Non‑responders (n=44) | p-value |

| Median age (yr) | 56 (38-65) | 59 (41-65) | 0.18 |

| Male sex (%) | 22 (75.9) | 31 (70.5) | 0.57 |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| - Adenocarcinoma | 14 (48) | 25 (57) | 0.49 |

| - Squamous cell | 15 (52) | 19 (43) | |

| ECOG 0‑1 (%) | 23 (79) | 34 (77) | 0.73 |

| Baseline PCT (ng/mL, median [IQR]) | 0.086 [0.052-0.097] | 0.089 [0.051-0.099] | 0.82 |

| EGFR mutation | 7 (24.1) | 10 (22.7) | 0.75 |

| ALK rearrangement | 1 (3.44) | 2 (4.5) | 0.37 |

| PDL1 > 1% | 2 (6.8) | 4 (9.09) | 0.14 |

Median age was 56 years (range 38–65) in responders and 59 years (range 41–65) in non responders (p = 0.18). The distribution of sex, ECOG performance status, histologic subtype, baseline serum PCT, EGFR mutation, ALK rearrangement, and PD L1 expression > 1% did not differ significantly between groups. These findings indicate that treatment response was not associated with baseline characteristics, supporting the validity of subsequent PCT kinetics comparisons.

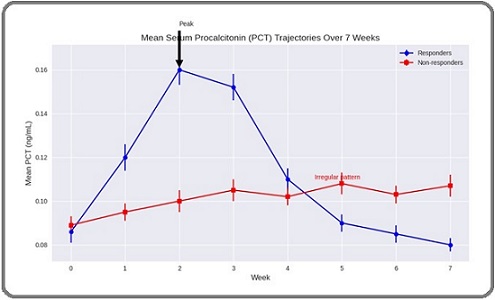

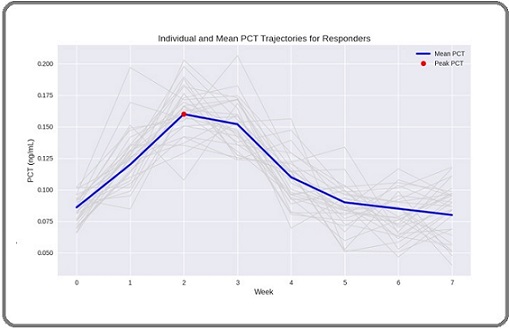

In responders, PCT peaked at week 2 (median 0.160 ng/mL, IQR 0.120–0.209) and/or week 3 (median 0.152 ng/mL, IQR 0.108–0.200), followed by a steady decline from week 4 onwards, reaching or falling to baseline by weeks 6–7. In contrast, non responders demonstrated stable or gradually increasing PCT levels without a clear early peak or subsequent decline (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2. Mean Serum Procalcitonin (PCT) Trajectories in Responders and Non Responders During Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy (cCRT).

Figure 3. Individual Patient PCT Pattern. Each grey line represent one patient and the blude line represents the mean of the whole group.

Mixed design repeated measures ANOVA revealed a highly significant Time × Response interaction (F = 12.4, p < 0.001), confirming distinct PCT trajectory patterns between groups. This effect remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, histology, and other factors.

At week 2, responders exhibited a median ΔPCT from baseline of +0.070 ng/mL (p < 0.001), whereas non responders showed no significant change (+0.011 ng/mL; p = 0.76). Week 3 results were similar, with no significant difference in peak timing between week 2 and week 3 among responders.

Binary logistic regression in SPSS v20 identified an early PCT rise ≥ 0.05 ng/mL at week 2 or week 3 as a strong independent predictor of treatment response (OR = 6.51, 95% CI 2.49–18.7, p < 0.001). Baseline PCT> 0.1 ng/mL was excluded from the model per protocol. Age, histology (adenocarcinoma vs. other), and EGFR mutation status were not significantly associated with response (Table 2).

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

| Early PCT rise ≥0.05 ng/mL (week 2/3) | 6.51 | 2.49-18.7 | <0.001 |

| Baseline PCT > 0.1 ng/mL | Excluded * | - | - |

| Age (per year) | 1.01 | 0.97-1.07 | 0.41 |

| Histology (adeno vs. others) | 1.17 | 0.54-2.49 | 0.68 |

| EGFR | 0.97 | 0.82-1.14 | 0.76 |

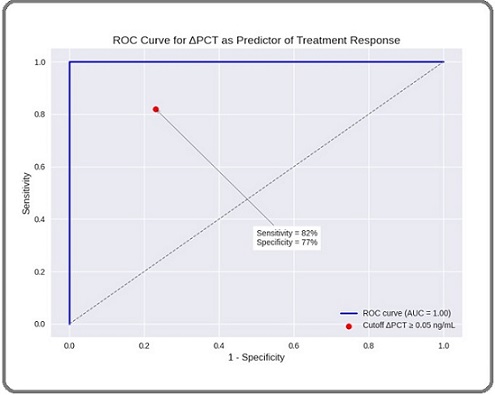

ROC Curve Analysis for week 2 ΔPCT yielded an AUC of 0.84 (95% CI 0.75–0.94, p < 0.0001). The optimal cut off (ΔPCT ≥ 0.05 ng/mL) predicted response with 82% sensitivity, 77% specificity, a positive predictive value of 73%, and a negative predictive value of 85% (Figure 3).

Figure 4. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve for ΔPCT at week 2 Relative to Baseline as a Predictor of Radiologic Response (CR/PR) at 4–6 weeks Post cCRT.

All responders demonstrated an early PCT peak (week 2 or 3) followed by a decline to baseline or lower before cCRT completion. Among those proceeding to surgery, 4 patients with documented PCT decline achieved major pathological response. Non responders either lacked an early peak or exhibited persistent elevation or irregular pattern. Patients with an early transient PCT rise and subsequent decline had a 90% positive predictive value for CR/PR, suggesting potential utility for early treatment adaptation.

The two treatment arms demonstrated comparable hematologic and gastrointestinal toxicity profiles. Additionally, longitudinal changes in procalcitonin were not significantly associated with any of the toxicities monitored.

Discussion

This prospective, multicenter investigation provides the first evidence that weekly serum PCT kinetics, analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20, can serve as a clinically informative biomarker for early response assessment in stage III NSCLC undergoing cCRT a setting in which actionable, real‑time biomarkers are urgently needed and totally lacking. A reproducible pattern of an early, transient rise in PCT (at week 2 or 3), followed by subsequent decline, was highly associated with favorable radiologic response (CR/PR) by RECIST. In contrast, non‑responders had flat or rising PCT curves, corroborating ongoing tumor progression or treatment failure.

Mixed design repeated measures ANOVA in SPSS, with a significant Time × Response interaction (F = 12.4, p < 0.001), confirms that responders and non‑responders have not only different average PCT concentrations, but fundamentally different kinetic trajectories, meeting the stringent requirements for a monitoring biomarker as articulated by current biomarker discovery and validation frameworks [11].

A binary logistic regression model in SPSS identified an early PCT rise ≥ 0.05 ng/mL at week 2 or 3 as a strong independent predictor of treatment response (OR = 6.51, 95% CI 2.49–18.7, p < 0.001), yielding high discrimination (AUC = 0.84) and reinforcing the potential role of PCT to guide pivotal decisions such as persisting with cCRT, prompt referral for surgery, or even escalation to novel experimental strategies (e.g., immunoradiotherapy) when early biomarkers indicate poor response.

The observed PCT pattern in responders an early peak followed by decline may reflect an acute, treatment‑induced tumor cell death with subsequent immune activation and transient systemic inflammatory response, distinct from infection or paraneoplastic syndromes [12]. This aligns with the phenomenon that cytotoxic therapy can result in a surge of damage-associated molecular patterns and cytokines, driving PCT elevation in the absence of infection [13] a feature specifically controlled for in our study through rigorous exclusion of infectious episodes.

Similar kinetic patterns in dynamic biomarkers have been reported for ctDNA, CEA, and even perfusion imaging parameters [14], but none are as widely available, inexpensive, or specificity‑controlled as PCT [15]. Notably, PCT is not meaningfully elevated by corticosteroid pre-medication or chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, making it feasible in the oncology population [16].

The ability to detect a characteristic PCT kinetic signature several weeks before conventional imaging confers a powerful temporal advantage in the management of stage III NSCLC. Patients who demonstrate the hallmark transient PCT rise by week 3 can be flagged as early responders, allowing multidisciplinary teams to proceed with surgical evaluation immediately after 45 Gy rather than awaiting delayed radiologic confirmation. Conversely, reliance on PCT trajectories can prevent unnecessary interruptions in cCRT for those already exhibiting favorable biomarker dynamics, ensuring that treatment continues uninterrupted. For patients who fail to mount an early PCT peak or whose levels continue to climb, clinicians may elect to intensify therapy whether by adding concurrent immunotherapy or by enrolling individuals in trials of novel agents long before radiographic progression becomes apparent. Ultimately, integrating dynamic PCT monitoring into routine workflows embodies the principles of precision oncology, providing real‑time risk stratification that has the potential to improve cure rates in stage III NSCLC [17].

Recent preclinical and translational data suggest optimal immunotherapy response integration shortly after the “danger signal” threshold induced by radiotherapy, which may coincide with the period of maximal effector T cell infiltration and immune reprogramming [18]. The observation that the PCT peak occurs at week 2–3 corresponds to this hypothesized window, suggesting that delivering concurrent anti‑PD‑1 or PD‑L1 therapy during this interval could maximize treatment synergies.

To date, only retrospective studies and cross-sectional analyses have examined PCT levels in lung cancer [8, 19]. While these have demonstrated prognostic associations of elevated baseline PCT with poor survival or treatment resistance, none have addressed serial, on-treatment PCT measurements longitudinally, nor attempted to link kinetics with early response or guide on-treatment management. Furthermore, most prior works have failed to prospectively exclude clinical infection, potentially confounding the interpretation of PCT rises [20].

Our study therefore fills an acknowledged gap there are no published prospective studies in lung cancer evaluating the dynamic course of PCT during curative- intent cCRT, making our data novel and of high clinical relevance. Procalcitonin as an easy, cheap and available test can serve as a biomarker that helps physicians decide whether to continue radiotherapy course after 45 Gy or to shift to surgical intervention. This can be achieved after adequate validation of our findings in larger prospective studies. The kinetics of procalcitonin levels in responding patients indicate that tissue damage due to radiation occurs in the third and fourth weeks of radiotherapy course. This damage leads to production of neoantigens which may maximize the effect of immunotherapy if administered within this window.

Compared with established biomarkers such as PD L1 and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), procalcitonin testing is more broadly available, technically simpler, and yields timely results that are unlikely to delay clinical decision making. However, ctDNA and PD L1 have been studied more extensively and enjoy a substantially higher level of supporting evidence than procalcitonin [21]. Accordingly, large prospective validation studies are required to determine the clinical utility of procalcitonin.

The association reported by Addai et al. between IL 39 and lung carcinoma subtypes reinforces the concept that tumor related immune/inflammatory signals are detectable in peripheral blood and may reflect both tumor biology and host response. In our cohort, dynamic changes in procalcitonin (PCT) during cCRT likely reflect noninfectious cancer and treatment associated inflammatory pathways as well as occult infection; the IL 39 findings provide independent evidence that tumor derived cytokine signatures can be measurable and clinically informative, suggesting complementary roles for cytokines like IL 39 and acute phase markers such as PCT in mechanistic and biomarker studies [22].

Another marker is serum neuron specific enolase (NSE) which has been shown to predict poorer response and survival in metastatic EGFR mutated NSCLC treated with gefitinib, highlighting that circulating tumor related biomarkers carry independent prognostic and predictive information and suggesting that combining tumor derived markers such as NSE with inflammatory markers like procalcitonin (PCT) may improve discrimination between tumor biology–driven inflammation and infection and enhance prediction of treatment response in stage III NSCLC an approach that warrants prospective evaluation in larger, histology stratified cohorts [23].

A high prevalence of cytomegalovirus DNA in NSCLC tissue was reported. It could lead to a tumor associated infection or local inflammatory processes which can influence systemic biomarker signals nevertheless procalcitonin; consequently, the need to account for occult or tissue localized infections when interpreting PCT dynamics during cCRT is reinforced, and integration of pathogen screening or molecular subgroup analyses into future biomarker studies is supported [24].

Our study’s strengths derive from its prospective, multicenter design and rigorous infection adjudication, which together minimize confounding and enhance the generalizability of our findings. By implementing weekly, protocolized serum PCT measurements, we captured high-resolution kinetic data that surpasses intermittent sampling approaches. The use of pre‑specified mixed‑effects repeated measures modeling in SPSS (version 20) further ensured robust analysis of time‑dependent trajectories, meeting current biomarker validation standards. To our knowledge, this report is the first to identify an actionable PCT kinetic signature for in‑course personalization of cCRT in stage III NSCLC.

Nevertheless, several limitations merit consideration. First, although our sample size provided sufficient power to detect significant PCT dynamics, it constrained the exploration of subgroup effects, such as differences by histologic subtype or molecular profile. Second, we did not directly correlate PCT kinetics with parallel mid-treatment biomarkers such as circulating tumor DNA or tumor‑infiltrating lymphocytes which may have offered complementary insights into tumor biology. Third, variations in platinum‐doublet regimens reflect real‑world practice but introduce heterogeneity that could influence systemic inflammatory responses. Finally, despite stringent exclusion of clinical infection, the potential for rare paraneoplastic syndromes or other non-infectious inflammatory processes to affect PCT cannot be fully excluded.

Looking forward, our findings call for validation in larger, independent cohorts and ideally within interventional frameworks to confirm the prognostic and predictive utility of PCT kinetics. Integrating PCT dynamics with emerging markers such as ctDNA and radiomic features may yield multi-parameter response models with enhanced accuracy. Evaluating biomarker-guided adaptive algorithms, including early treatment escalation or de‑escalation based on PCT changes, could optimize therapeutic decision-making. Finally, prospective trials designed to synchronize immunotherapeutic interventions with the identified PCT kinetic window hold promise for amplifying the synergistic effects of chemoradiation and immunomodulation.

In conclusions, this study establishes, for the first time, that dynamic monitoring of serum procalcitonin provides a robust, minimally invasive, and widely available biomarker for early response detection during concurrent chemoradiotherapy in stage III NSCLC. The distinct pattern of a transient PCT rise at week 2-3 followed by decline identifies patients likely to achieve radiologic and pathologic response, supporting personalized treatment adaptation. Incorporating real-time PCT kinetics into clinical workflows may enable earlier surgical referral, avoidance of unnecessary delays, and timely treatment escalation for non-responders. These observations should be prospectively validated, and inform the design of future biomarker-driven trials in locally advanced lung cancer.

Clinical trial registration

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the faculty of medicine, Menoufia University.

Consent for participation and publishing

All participants provided written informed consent to be involved in the study. Declaration of Helsinki was followed for the conduction and reporting of this study.

Authors’ contributions

All authors substantially contributed to the study’s conception and design, implementation, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. They each participated in drafting or critically revising the manuscript, provided final approval of the version to be published, selected the target journal, and accept full responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere appreciation to all patients who generously participated in this study. We also acknowledge the valuable contribution of the Dream Biostatistics Office, whose expertise in conducting rigorous statistical analyses and providing comprehensive methodological descriptions greatly facilitated the preparation of this manuscript.

Declaration on the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

A large language model–based artificial intelligence tool was employed exclusively for linguistic refinement of this manuscript. As all authors are non-native English speakers, Copilot® was utilized for proofreading and grammar correction. No generative AI applications were used in the conception, analysis, or reporting of this study.

References

- Combined Chemoradiotherapy Regimens of Paclitaxel and Carboplatin for Locally Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Randomized Phase II Locally Advanced Multi Modality Protocol Belani CP , Wang W, Johnson DH , Choy H, Bonomi P, Scott C, Travis P, et al . Journal of Clinical Oncology.2005;23(25). CrossRef

- Management of Stage III Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: ASCO Guideline Daly ME , Singh N, Ismaila N, Wakelee HA , Spigel DR , Higgins KA , Komaki R. Journal of Clinical Oncology.2022;40(12). CrossRef

- Overall Survival with Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC Antonia SJ , Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui RA , Kurata T. New England Journal of Medicine.2018;379(24). CrossRef

- Early Radiologic and Metabolic Tumour Response Assessment during Combined Chemo Radiotherapy for Locally Advanced Non Small Cell Lung Cancer Tvilum M, Knapp MM , Hoffmann L, Khalil AA , Appelt AL , Haraldsen A, Alber M, et al . Clinical and Translational Radiation Oncology.2024;48. CrossRef

- Minimally Invasive Biomarkers for Triaging Lung Nodules—Challenges and Future Perspectives Afridi WA , Picos SH , Bark JM , Stamoudis DAF , Vasani S, Irwin D, Fielding D, Punyadeera C. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews.2025;44. CrossRef

- Procalcitonin and the Calcitonin Gene Family of Peptides in Inflammation, Infection, and Sepsis: A Journey from Calcitonin Back to Its Precursors Becker K.L., Nylén E.S., White J.C., Müller B., Snider R.H.. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.2004;89(4). CrossRef

- Prognostic Impact of Serum Procalcitonin in Non Small Cell Lung Cancer Kajikawa S, Ohashi W, Kato Y, Fukami M, Yonezawa T, Sato M, Kosaka K, et al . Tumori Journal.2020;107(5). CrossRef

- Inflammatory Markers and Procalcitonin Predict the Outcome of Metastatic Non Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Receiving PD 1/PD L1 Immune Checkpoint Blockade Nardone V, Giannicola R, Bianco G, Giannarelli D, Tini P, Pastina P, Falzea AC , et al . Frontiers in Oncology.2021;11. CrossRef

- PET/CT Imaging in Lung Cancer Schlarbaum KE . Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology.2024;52(2). CrossRef

- New Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours: Revised RECIST Guideline (Version 1.1 Eisenhauer EA , Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH , Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J. European Journal of Cancer.2009;45(2). CrossRef

- Modeling and Systematic Analysis of Biomarker Validation Using Selected Reaction Monitoring Gargari A, Esmaeil UMN , Dougherty ER . EURASIP Journal on Bioinformatics and Systems Biology.2014;1. CrossRef

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Procalcitonin in Adult Non Neutropenic Cancer Patients with Suspected Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis Lee Y, Yeh HT , Lu SW , Tsai YC , Tsai YC , Yen CC . BMC Infectious Diseases.2024;24(1). CrossRef

- Immunogenic Cell Death in Cancer Therapy Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Nature Reviews Immunology.2012;12(12). CrossRef

- Early Circulating Tumor DNA Kinetics as a Dynamic Biomarker of Cancer Treatment Response Li A, Lou E, Leder K, Foo J. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics.2025;9. CrossRef

- Procalcitonin and Its Limitations: Why a Biomarker’s Best Isn’t Good Enough Farooq A, Franco JMC . The Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine.2019;3(4). CrossRef

- Procalcitonin Is Not Influenced by Corticosteroid Pretreatment and Neutropenia in Patients with Hematological Malignancies Schaub N, Reichert A, Ulrich M, Georg TW , Bergwelt Baildon M. Annals of Hematology.2015;94(3). CrossRef

- Emerging Precision Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy for Patients with Resectable Non Small Cell Lung Cancer: Current Status and Perspectives Godoy LA , Chen J, Ma W, Lally J, Toomey KA , Rajappa P, Sheridan R, Mahajan S, Stollenwerk N, Phan CT , Cheng D, Knebel RJ , Li T. Biomarker Research.2023;11(1). CrossRef

- Combining Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer: Timing, Mechanisms, and Translational Opportunities Demaria S, Formenti SC , Galluzzi L. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology.2023;20(9). CrossRef

- Prognostic Significance of Procalcitonin in Small Cell Lung Cancer Ichikawa K, Watanabe S, Miura S, Ohtsubo A, Shoji S, Nozaki K, Tanaka T, et al . Translational Lung Cancer Research.2022;11(1). CrossRef

- Role of Procalcitonin and Interleukin 6 in Predicting Cancer, and Its Progression Independent of Infection Chaftari AM , Hachem R, Reitzel R, Jordan M, Jiang Y, Yousif A, Mulanovich V. PLOS ONE.2015;10(7). CrossRef

- The Clinical Utility of Dynamic Circulating Tumor DNA Monitoring in Inoperable Localized Non Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Chemoradiotherapy Yin Y, Zhang T, Wang J, Wang J, Xu Y, Zhao X, Ou Q, et al . Molecular Cancer.2022;21(117). CrossRef

- A Role of Serum Interleukin-39 and Association with Small and Non-Small Cell Carcinoma in Lung Cancer Patients Addai Ali H, Hatif Hammood N, Saleh Mashkour M, Addya Ali R, Abdulameer Noman W, R.Al-Ameer L, F.Karam F, Swadi Zghair F, Alrufaie MM . Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.2025;1;26(9):3299-3307. CrossRef

- Predictive and Prognostic Significance of Serum Neuron Specific Enolase in Patients with Metastatic Non Small Cell Lung Cancer Receiving Gefitinib: A Prospective Study from South Egypt Cancer Institute Abdalla A.Z., Khallaf S.M., Mohammed D.A., Mounir M.G., Mohammed A.H.. Asian Pac J Cancer Care.2025;26(7). CrossRef

- High Proportion of Cytomegalovirus DNA from Tissue Samples of Non Small Cell Lung Carcinoma in Persahabatan Hospital National Respiratory Center, Indonesia Dharmawan I.N.I.P., Zaini J., Pratomo I.P., Rahardjo E., Faisal H.K.P., Soehardiman D., Samoedro E., et al . Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.2025;26(6). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2025

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times