Innovative Practice Report on Nurse-led Interfaith Symbol Translation and Adaptive Clinical Nursing Technology: A Qualitative Interview-based Study

Download

Abstract

Introduction: To summarize and analyze the innovative, culturally adaptive interventions developed and implemented by frontline oncology nurses to resolve conflicts between patients’ religious practices and clinical care protocols.

Materials and Methods: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nurses working in a hospital oncology department. The interviews focused on documenting real-world challenges and the practical solutions nurses created in response to patients’ religious needs. Through thematic analysis of the interview data, three representative cases were summarized, detailing the nurses’ interventions for Buddhist chanting, Muslim Ramadan fasting, and Christian cross-holding.

Results: The analysis documented several nurse-led interventions that successfully resolved clinical conflicts. To manage chanting-induced blood pressure fluctuations, nurses developed and introduced a “mantra counting breathing card” to guide rhythmic breathing. For a fasting Muslim patient at risk of hypoglycemia, nurses designed and implemented a sunset-centered, time-phased intravenous infusion schedule. In the case of ECG interference from a metal cross, nurses innovated by applying a medicalgrade silicone pad to shield the object, which eliminated the artifact. These nurse-initiated solutions were reported to enhance patient compliance and psychological comfort.

Conclusion: This study summarizes a transferable framework for faith-sensitive care derived directly from the clinical innovations of frontline nurses. It demonstrates that nurses are pivotal agents in culturally adaptive care, capable of creatively translating religious symbols into safe clinical practices. By documenting and systematizing these grassroots innovations, this research provides a model for leveraging existing nursing expertise to reconcile cultural needs with medical requirements, promising improved patient-centered outcomes in multi-faith settings.

Introduction

Cancer is one of the most common causes of death worldwide. Current treatment options for cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy [1, 2]. However, humanitarian care for patients is also important and necessary. In an oncology ward, a Buddhist patient repeatedly chanted Buddhist scriptures before surgery, which caused blood pressure fluctuations and delayed anesthesia induction; a Muslim patient’s Eid fasting triggered hypoglycemic shock, and a Christian’s holding a metal cross to his chest affected the results of an electrocardiogram, among others. These scenarios reveal a central paradox: modern medical technology attempts to standardize processes but struggles to respond to the physiological-psychological needs derived from patients’ cultural beliefs, and technological innovations in cross-cultural care based on empirical data are urgently needed. Existing studies have mostly considered religious rituals as objects of ‘cultural sensitivity training’, but have neglected their function as non-pharmacological regulatory tools, and their non-pharmacological intervention value has been underestimated. Existing studies have shown that religion can help cancer patients better adapt to and cope with the disease psychologically [3-5]. Religion and spirituality can be helpful for patients and their caregivers from diverse cultural backgrounds to cope with cancer [6]. Spiritual care is a fundamental component of high-quality compassionate health care and it is most effective when it is recognized and reflected in the attitudes and actions of both patients and health care providers. A focus on spirituality improves patients’ health outcomes, including quality of life [7]. Studies show that while clinicians such as nurses and physicians regard some spiritual care as an appropriate aspect of their role, patients report that they provide it infrequently [8]. Nurses lack a systematic approach to transforming patients’ ritual behaviors into physiological intervention strategies, resulting in a dichotomy between ‘technological intervention’ and ‘cultural needs’. Religious affiliation influences healthcare preferences and the implementation of clinical care practices. This increasingly multicultural society presents healthcare providers with a challenging task: providing appropriate care to individuals with different life experiences, beliefs, value systems, religious beliefs, languages, and healthcare perspectives [9]. Healthcare providers must be equipped with appropriate knowledge and skills to address these spiritual needs effectively [10]. The research significance lies in the following: to solve the problem of ‘decoding cultural symbols’ and ‘adapting technology’, and to develop nursing technology solutions that can be directly applied to clinical practice. The significance of the research lies in: breaking the binary opposition between “cultural sensitivity” and “operational norms”, revealing the correlation mechanism between religious ritual behavior and physiological indicators, and explaining that religious and spiritual traditions can become a rich theoretical basis and practical service resource [11], providing a reference for optimizing nursing operations and providing low-cost, highly feasible cultural adaptation solutions for resource-constrained settings where advanced treatment modalities may not be readily available [12].

This study aimed to explore, through semi-structured interviews with oncology nurses, the representative clinical challenges and innovative solutions arising from patients’ religious practices. By summarizing and analyzing three emblematic cases (involving Buddhist chanting, Muslim Ramadan fasting, and Christian cross-holding), we sought to codify a nurse-led, culturally adaptive intervention framework. The ultimate goal was to develop a transferable model for safely integrating faith-based practices into standard oncology care, thereby mitigating physiological conflicts and enhancing patient-centered outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Design

This qualitative study employed a semi-structured interview approach to explore nurses’ experiences and perspectives regarding cultural-clinical conflicts in an oncology setting. The primary objective was to identify and summarize representative cases where religious practices intersected with clinical care, and to derive practical nursing interventions. This pilot study was guided by a constructivist/interpretivist paradigm, emphasizing the socially constructed nature of clinical reality and the importance of understanding nurses’ interpretive accounts. The study design was exploratory and descriptive, aiming to generate rich, context-specific insights rather than to test pre-defined hypotheses.

Sample

Purposive sampling was used to recruit nurses working in the oncology department of a tertiary care hospital. Participants were eligible if they had at least one year of direct patient care experience and had encountered situations where patients’ religious practices influenced or conflicted with clinical outcomes. Sampling continued until thematic saturation was reached the point at which no new significant themes emerged from subsequent interviews. A total of 15 nurses were interviewed over a one-month period. From these interviews, three emblematic cases were selected for in-depth analysis each representing one of the target religious groups (Buddhism, Islam, Christianity). The selection of these cases was based on their clarity, representativeness of common conflicts, and the richness of the adaptive interventions described.

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in person by the principal investigator in a private room within the hospital to ensure confidentiality and minimize disruption. Each interview was audio-recorded with participant consent and transcribed verbatim by a trained research assistant. The interview guide was developed based on a review of the literature and preliminary discussions with two senior oncology nurses (not included in the study sample). The guide included open-ended questions and probes covering four key areas: (1) descriptions of specific incidents involving religious practices; (2) observed physiological or clinical conflicts; (3) nursing responses and interventions; and (4) patient reactions and outcomes. Interview durations ranged from 30 to 60 minutes. Field notes were also taken to capture non-verbal cues and contextual details.

Data Analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis, following the six-phase approach outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). Initially, two researchers independently performed open coding on the first three transcripts to identify key incidents, nursing responses, and perceived outcomes. Codes were then discussed and consolidated into a preliminary coding framework. This framework was applied to the remaining transcripts, with new codes added iteratively as needed. Codes were subsequently grouped into broader thematic categories based on conceptual similarity. From these categories, three representative cases were synthesized to illustrate the most salient cultural-clinical conflicts and adaptive strategies. Physiological data (e.g., BP, glucose, ECG) mentioned in the interviews were summarized descriptively to contextualize the clinical impact of each case. To enhance analytical rigor, regular peer debriefing sessions were held among the research team to challenge interpretations and ensure consistency.

Results

The following three cases were synthesized from interviews with oncology nurses, illustrating typical scenarios where religious practices intersected with clinical care.

1. Buddhists: Mantras Regulate Autonomic Nervous System Function

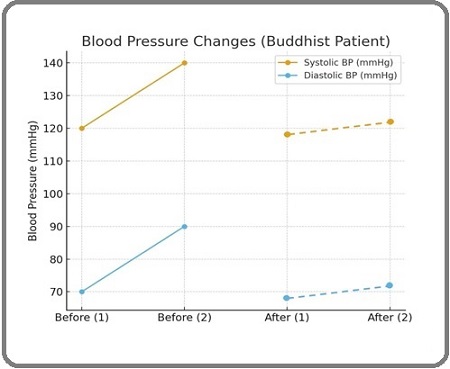

A 63-year-old Thai Buddhist patient chanted mantras silently for 30 minutes the morning before surgery, resulting in blood pressure fluctuations as high as ±20 mmHg (Table 1).

| Patient ritual behavior | Time | Nurse Response | physiological indicators |

| Buddhist patient reciting mantras silently before surgery | During pre-anesthesia period, before second surgery induction | Introduced and explained the use of the " Mantras counting breath card" | BP fluctuation: 140/90 mmHg to about 120/70 mmHg (±20 mmHg) |

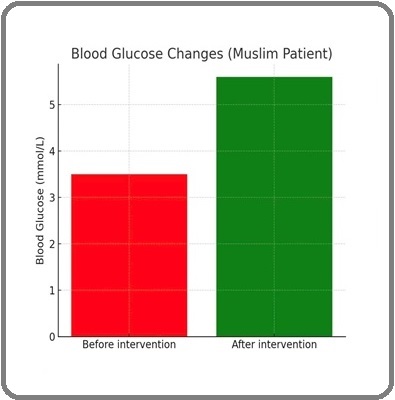

| Muslim patient fasting during Ramadan | 06:00 - 19:00 (Daytime) | Initiated circadian rhythm-adapted IV infusion protocol | Blood glucose: 3.5 mmol/L (at 16:00); stabilized at 5.6 mmol/L post-infusion |

| Christian patient holding metal cross on chest | During ECG monitoring | Placed medical-grade silicone cushion over electrode | ECG signal artifact resolved; clear waveform obtained |

This delayed anesthesia and prevented surgery that day. The nurse observed a negative correlation between the mantra rhythm and respiratory rate. Under the nurse’s guidance, the mantra rhythm was adjusted to a standard breathing pattern of 6 breaths per minute. The nurse also created “mantra counting breathing cards” to guide the patient in adjusting the meditation rhythm. After the intervention, the patient underwent elective surgery and used the breathing cards to guide chanting before anesthesia. The standard deviation of blood pressure before and after chanting decreased and remained stable (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Blood Pressure Changes (Buddhist Patient).

2. Muslims: Metabolic Interventions for Eid Fasting

A 68-year-old male Muslim cancer patient from Saudi Arabia observed a daytime fast during Ramadan and refused to drink water. This resulted in a blood glucose level of 3.5 mmol/L at 4 pm (Table 2), indicating hypoglycemia.

| Period | Nursing focus | Nursing Operations |

| Sunset → Maghrib (Iftar) | Quick energy boost | 1. Start the first round of intravenous nutrition (such as glucose + electrolytes) immediately after the adhan of Maghrib. 2. The initial rate is adjusted to 80% of the normal rate, and resumes the full rate after 30 minutes if there is no discomfort (such as a sudden increase in blood sugar). |

| Maghrib → midnight (free feeding period) | Maintain a stable nutritional supply | 1. Switch to full balanced intravenous nutrition (such as amino acids + fat emulsion + trace elements), and adjust the rate according to the patient's metabolic needs. 2. Monitor blood sugar/electrolytes every 2 hours. 3. Oral solid food is recommended for patients who can eat independently |

| From Midnight → Before Fajr (Suhoor preparation period) | Prolong satiety and store energy during the day | 1. Add hypertonic glucose (10%) 1 hour before the end of Suhoor to delay hunger during the daytime. 2. For diabetic patients, use sustained-release fat emulsion (such as SMOF) to reduce daytime blood sugar fluctuations. |

| Fajr → sunset (Fast time) | Ensure basic medical needs while respecting fasting practices | 1. For patients who are not critically ill and insist on fasting: stop the infusion and pay attention to monitoring all vital signs. 2. For patients who are critically ill and insist on fasting: explain the necessity of infusion to the patient and family members, and contact the local Islamic association to explain the basis of medical exemption to the patient. |

Older patients may not be able to tolerate the conventional chemotherapy due to its toxicity [13]. The toxicity of chemotherapy combined with the physical weakness caused by a restricted diet is extremely detrimental to cancer treatment. The nurse implemented a phased intravenous nutrition regimen (Figure 2): 60% of the daily caloric requirement was administered after sunset, and blood glucose was regulated using an insulin pump that aligned with the fasting-feeding cycle.

Figure 2. Blood Glucose Change (Muslim Patient).

Quranic verses regarding recovery were printed on the infusion schedule. The patient called this schedule “God’s timer.” After the intervention, blood sugar levels stabilized at 5.6 mmol/L (Table 2), and treatment adherence improved.

3. Christians: The Cross as a Psychological Support

A 78-year-old Polish patient placed a metal cross on his chest during electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring, which resulted in persistent signal artifacts. A nurse placed a medical-grade silicone pad over the electrodes, resolving the interference and producing clear waveforms. This technical improvement allowed examinations to be performed without requiring the cross to be removed. Following the intervention, the patient’s engagement with the treatment process improved.

Discussion

The following discussion illustrates the findings from our interview-based pilot study, which summarized three representative cases. It was important to emphasize that the insights and mechanisms proposed in this article are intended to construct a conceptual framework for understanding how religious rituals might be systematically translated into nursing interventions, based on the analysis of three representative cases derived from nurse interviews. While conceptually innovative, these propositions require larger-scale validation to confirm their generalizability and validity.

1. Case study

The integration of spiritual care within nursing practice can be understood as a component of person-centered care and humanized focus on supporting patients’ search for meaning and support during illness. Furthermore, an awareness of the need to provide spiritual support to patients can promote and enhance support of dignity and compassionate approaches to care for those patients for whom faith or spirituality is important. Spirituality, though defined and interpreted differently based on individual experiences and worldviews, is a fundamental aspect of our lives that provides meaning for some around experiences. Spirituality plays a crucial protective role in health and well-being that can alleviate challenging crises in patients and caregivers in healthcare settings. Spirituality is not a static phenomenon; rather, it is a dynamic source of strength [14].

1.1 In response to the Buddhist chanting behaviors, the nurse cleverly used the respiratory-blood pressure coupling effect

Low-frequency respiration during silent chanting of Buddhist scriptures may activate the parasympathetic nerves, inducing bradycardia and fluctuations in blood pressure. By standardizing the breathing rhythm (6 breaths/ minute), the nurse transformed the original disorderly chanting into a rhythmic breathing exercise to stabilize blood pressure. In this specific case, the nurse-developed ‘Mantras Counting Breathing Cards’ suggest a potential pathway for transforming the religious behavior of chanting into a structured, quantifiable breathing exercise, which was associated with reduced blood pressure fluctuations and may contribute to anxiety management. Anxiety management and physiological stabilization. Rather than denying the religious significance of chanting, the nurse combines its ritualized features (repetition, rhythm) with biofeedback techniques, giving traditional practices a new therapeutic function. This case illustrated a potential model for culturally appropriate innovation, by exploring the functional utility of an act of faith within a clinical context. Oncology nurses must be aware of their patients’ specific cultural values and religious beliefs when providing care to them [15] and need to understand the spiritual needs of patients in order to provide better care [16]. Therefore, religiosity is the resource used by cancer patients to help cope with the disease [17].

1.2 To address the metabolic characteristics of Muslims in Ramadan

Daytime fasting leads to diurnal fluctuations in insulin sensitivity, postprandial hyperglycemia easily occurs after eating at night, and prolonged fasting may trigger hypoglycemia. This shows that Muslim patients’ cognition and behavior towards cancer are influenced by social and cultural factors [18]. Cancer patients are highly susceptible to short- and long-term nutritional problems related to their underlying disease and to side effects of multimodal treatment [19], and inadequate nutritional intake will aggravate malnutrition and worsen the condition. Nurses should actively assess changes in clinical signs in cancer patients, and it is crucial to select appropriate nutritional interventions for patients with religious beliefs to maximize the nutritional status of patients and improve their survival and quality of life [20]. For this patient, nurses designed a ‘sunset centralized infusion + dynamic insulin pump’ program in an attempt to better align with the physiological eating window and to prevent metabolic disorders. Religious adaptation of blood glucose fluctuation: delaying the infusion of 60% of calories until after sunset not only complies with the fasting rule but also conforms to the human circadian rhythm (cortisol secretion peaks in the early morning), reducing the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia. Patients associated the infusion schedule with religious symbols (Allah) as “timepieces of Allah”, creating cognitive coordination, a reinterpretation of cultural symbols that reduces treatment resistance and reflects the positive drive of cultural beliefs towards health behaviors. Nurses adjusted the infusion schedule according to the Islamic calendar, an approach that aimed to synchronize medical care with religious rituals and which, in this instance, appeared to be associated with improved patient compliance. Research indicates that cancer patients who rely on spiritual and religious beliefs to cope with their illness are more likely to use an active coping style in which they accept their illness and try to deal with it positively and purposefully [21].

1.3 Faith practices may be particularly helpful in improving spiritual well-being among Christians [22].

Patients view the cross as a talisman or spiritual support so forcibly removed may trigger resistance, the nurse complied with the principles of cultural sensitivity in the nursing process: respecting the patient’s beliefs and establishing trust with the patient. Dignified care protects the patient’s rights and provides appropriate ethical care while improving the quality of nursing care [23]. The nurses use silicone pads to isolate the contact between the metal cross and the skin to reduce current interference, and at the same time, maintain stable contact between the electrodes and the skin. This ensures the accuracy of the signals. In this case, the approach was low-cost and easy to use, offering a means to avoid direct interference with the patient’s religious object. The nurse demonstrated respect for cultural practices by resolving the conflict through technical means. The nurse’s initiative conveys a message of ‘respect for personal choice’ and enhances the patient’s sense of acceptance, which leads to cooperation with the treatment, a non-confrontational approach that helps to build trust between the patient and the practitioner. A bond between doctor and patient that is based on trust has been an integral part of patient care and has been described to promote recovery, reduce relapse, and enhance treatment adherence [24]. In this case, the synergy of technical adjustment and cultural respect achieved a win-win situation, successfully reconciling the medical goal of obtaining a clear ECG reading with the patient’s need to retain his religious object. By explaining that ‘adjustments are made to ensure the accuracy of the examination’, the nurse combines technical needs with the patient’s beliefs, so that the patient understands the need to make adjustments rather than being forced to compromise.

2. Clinical Translation Pathway

Although culturally sensitive nursing is highly valued today, patients may come from different countries and have different cultural norms, expectations, and behaviors [25]. Therefore, uniform nursing behaviors may not meet the needs of patients, which requires nurses to take some targeted support measures. Based on the above case study and evaluation, a systematic clinical translation strategy is proposed below, aiming to extend culturally sensitive nursing interventions to a wider range of contexts, while ensuring medical validity and ethical compliance:

2.1 Cultural Competence and Standardized Training

2.1.1. Development of a Cultural Decoding Toolkit

Establishment of a list of contraindications and a library of adapted protocols for the mainstream religions (Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, etc.), e.g., contraindications, adaptations, and protocols. Develop a library of contraindication lists and adaptive solutions covering mainstream religions (Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, etc.), e.g.: contraindication lists: metal interference (EKG), metabolic management during fasting period, conflict between prayer time and treatment; adaptive solutions: replacement of silicone cushion, time-slot infusion, respiratory rhythm restructuring; Symbol Meaning Quick Reference Handbook: analyze the potential physiological/psychological functions of common religious symbols (crucifixes, Buddhist beads, worship actions), and guide healthcare workers to quickly identify translatable resources.

2.1.2 Establish a training system

Spirituality was an important part of the care for the nurses when meeting the needs of their patients and the patients’ families. Therefore, nursing education should enhance nurses’ understanding and awareness of spiritual issues and prepare them to respond to human spiritual needs [26]. To enhance competency, it is recommended to implement structured, continuous in-service education programs on spiritual care practices, such as providing training on ‘cultural precision nursing’ for nurses with serious and chronic illnesses, combined with case simulations (e.g., metabolic control during Ramadan, meditative behavioral interventions) and collaborating with religious consultants and anthropologists to train healthcare workers to interpret patient behavior from the perspective of belief systems to strengthen technical and cultural synergies. Additionally, support should be provided for nurses’ personal and professional development, addressing factors such as work–life balance and family commitments [27].

2.2 Technology adaptation and tool innovation

2.2.1 Religion-adapted medical tool development

Production of low-cost intervention kits: to address the problem of metal interference, develop medical-grade silicone products in different shapes (electrode patch pads, necklace fixation pads); upgraded version of the respiratory counting card: embedded with an adjustable LED to indicate the rhythm of respiration (e.g., flashing 6 times/minute), adapted to different religious meditation scenarios; integration of Islamic calendars, Islamic charts, and other medical devices in insulin pumps and monitors.

2.2.2 Evidence-based technology validation process

Cultural appropriateness test: before the promotion of the new tool, conduct a small-sample cultural appropriateness test (e.g., inviting Buddhists to experience the breath counting card), and collect feedback to optimize the design. Cross-cultural validity studies: Compare the difference in effectiveness between standardized and culturally appropriate interventions (e.g., ECG quality in the silicone pad group versus the traditional metal removal group) to drive guideline updates.

2.3 Interdisciplinary Collaborative Processes

2.3.1 ‘Faith Advisor’ Consultation System

Collaborate with the hospital’s Religious Office to initiate a multidisciplinary consultation for complex cases (e.g., a patient of a particular religion who refuses to have a blood transfusion) and produce a written adaptation plan.

2.3.2 Nurse-pharmacist-dietitian linkage

In response to the fasting needs of Muslim patients, confirm the alcohol content of medications with the pharmacy department in advance, and design enteral nutrition formulas in line with the metabolic characteristics of Ramadan with the nutrition department.

2.4 Culture-related risk plan

2.4.1 Hypoglycemia emergency kit

Equip Ramadan patients with ‘Allah’s First Aid Box’ containing glucose gel, labeled with Arabic/English instructions, to ensure that it can be used in emergencies when they are not awake.

2.4.2 Alternative to metal interference

In case of allergy to silicone pads, an alternative to conductive paste + gauze wrapped around the metal object, with an explanation to the patient.

2.4.3 Add a ‘cultural appropriateness statement’ to the informed consent form, e.g.,

‘This protocol has been adapted to your beliefs and practices, and the specific risks and benefits have been included.’

3. limitations

3.1 While this study pioneers a practical framework for integrating religious practices into clinical nursing, its scope necessitates cautious interpretation

The culturally adaptive interventions discussed by nurses were implemented in their specific clinical contexts. Consequently, direct application to other healthcare systems or faith traditions requires further validation. Additionally, the one-month observation period prioritized capturing immediate physiological responses to ritual-technological integration, leaving longer-term sustainability effects (e.g., adherence to breathing standardization protocols post-discharge) as an avenue for future investigation. Future research should include a full-scale with a larger sample size to further validate these findings [28].

3.2 A key limitation is that the interventions and their outcomes were reported by the nurses themselves

There was no independent assessment or use of validated patient-reported outcome measures to corroborate these reports, which introduces the potential for reporting bias. Future research should incorporate independent evaluations to objectively confirm the efficacy suggested by this exploration.

In conclusion, this study proposed a new framework for understanding and resolving cultural-clinical conflicts in oncology nursing. The continuous advancement of globalization has made medical and health professionals more aware of the importance of multicultural nursing [29]. Nurses must integrate the patient’s cultural background with clinical practice to provide culturally appropriate care, thereby respecting individual choices while reconciling traditional values and further optimizing nursing services [30], leaping over cultural conflict to nursing innovation. In a globalized context, the core competency of nurses lies not only in their professional skills but also in their ability to build a two-way empowering mechanism of “cultural sensitivity-technical precision.” The synergy between technical adaptation and cultural respect can achieve a win-win situation in balancing medical goals and patient needs. Successful treatment relies not only on professional expertise but also on attention to the patient’s psychosocial context and the ability to resolve potential conflicts with empathy and creative thinking. Furthermore, nursing itself embodies the spirit of compassion shared by many religions whether it’s the Buddhist concept of “compassion,” the Islamic concept of “duty to do good,” or the Christian concept of “love your neighbor as yourself” all of these concepts resonate with the empathy and dedication inherent in the nursing profession. Understanding this connection can help nurses rekindle their sense of purpose amidst their demanding workload and treat patients with greater spirituality. The results suggested that religious rituals may have the potential to serve as an interface between physiological and psychological interventions. Rather than being an obstacle to the medical process, religious rituals serve as a natural interface between physiological and psychological interventions. Cultural adaptation is not a compromise but an innovation, and nurses, through their professional judgment, can transform cultural beliefs into therapeutic resources. However, it is important to emphasize that this study provided a transferable template for future research to build upon. The effectiveness of the proposed model requires rigorous validation in larger, controlled studies across diverse cultural and clinical settings.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical Statement

This qualitative study was conducted in accordance with the core ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research involved semi-structured interviews with oncology nurses to summarize and analyze de-identified clinical cases. This study is essentially a summary of nursing quality management and educational innovation. Its core purpose is to summarize and disseminate excellent clinical practice experience, rather than conducting a prospective study on “human subjects”. In commitment to the highest standards of research integrity, the following stringent ethical safeguards were implemented and upheld throughout the research process:

1. Informed Consent: Prior to the interviews, all nurse participants were provided with a detailed information sheet and gave written informed consent. The consent process explicitly detailed the study’s aims, the voluntary nature of participation, the right to refuse to answer any question or withdraw at any time without consequence, and all measures for ensuring confidentiality.

2. Protection of Anonymity

a. Nurse Participants: All potentially identifying information of the interviewed nurses (e.g., names, specific workplace details, colleagues’ names) has been rigorously removed from the transcripts and the final manuscript. Participants are referred to using non-identifiable codes (e.g., Nurse A, Nurse B).

b. Patient Cases: The clinical cases described by the nurses are presented as fully de-identified, composite scenarios. All specific patient identifiers (e.g., exact age, nationality, unique medical details) have been altered or generalized to prevent any possibility of identification, ensuring the cases are illustrative but not linked to real individuals.

3. Data Security: All audio recordings and interview transcripts were stored on a password-protected secure server. Audio recordings were permanently deleted following verbatim transcription and validation.

4. Minimal Risk: The study was classified as minimal risk as it involved discussions with healthcare professionals about their standard work experiences and did not involve any clinical intervention or access to sensitive personal patient records.

The authors affirm that the welfare and rights of all individuals involved have been the paramount consideration throughout this study.

Conflict of interest Statement

The author declares no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, related to this work. No funding sources influenced the design, execution, or reporting of this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all anonymous patient participants for their profound collaboration, whose courage and cultural resilience inspired this work. The authors thank the spiritual counsellors from the local Buddhist, Islamic, and Christian communities for their background insights. Thank you to our family and friends for their support and help.

Author contributions

Zhenyu Zou: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing (Original Draft, Editing), Visualization, Project Administration.

Bingyan Zhai: Conceptualization, Review.

References

- Outcome of hypofractionated breast irradiation and intraoperative electron boost in early breast cancer: A randomized non-inferiority clinical trial Fadavi P, Nafissi N, Mahdavi SR , Jafarnejadi B, Javadinia SA . Cancer Reports (Hoboken, N.J.).2021;4(5). CrossRef

- Clinical Efficacy and Side Effects of IORT as Tumor Bed Boost During Breast-Conserving Surgery in Breast Cancer Patients Following Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Homaei Shandiz F, Fanipakdel A, Forghani MN , Javadinia SA , Mousapour Shahi E, Keramati A, et al . Indian Journal of Gynecologic Oncology.2020;18(2):46. CrossRef

- Religion and cancer: examining the possible connections Crane JN . Journal of Psychosocial Oncology.2009;27(4). CrossRef

- Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of Concurrent Use of Crocin During Chemoradiation for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Ebrahimi N, Javadinia SA , Salek R, Fanipakdel A, Sepahi S, Dehghani M, Valizadeh N, Mohajeri SA . Cancer Investigation.2024;42(2). CrossRef

- Efficacy of Melatonin in Alleviating Radiotherapy-Induced Fatigue, Anxiety, and Depression in Breast Cancer Patients: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial Sadeghi Yazdankhah S, Javadinia SA , Welsh JS , Mosalaei A. Integrative Cancer Therapies.2025;24. CrossRef

- Influence of religion and spirituality on head and neck cancer patients and their caregivers: a protocol for a scoping review Seneviwickrama M, Jayasinghe R, Kanmodi KK , Rogers SN , Keill S, Ratnapreya S, Ranasinghe S, Denagamagei SS , Perera I. Systematic Reviews.2025;14(1). CrossRef

- Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus Puchalski CM , Vitillo R, Hull SK , Reller N. Journal of Palliative Medicine.2014;17(6). CrossRef

- Spirituality and religion in oncology Peteet JR , Balboni MJ . CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2013;63(4). CrossRef

- Cultural and religious considerations in pediatric palliative care Wiener L, McConnell DG , Latella L, Ludi E. Palliative & Supportive Care.2013;11(1). CrossRef

- Awareness, Practices and Challenges of Myanmar Health Professionals in Spiritual Care for Advanced Cancer Zu Wah WM , Tin TMH, , Aye SM . International Journal Of Care Scholars (ISSN: 2600-898X).2025;8(2):3-10. CrossRef

- Nursing research on religion and spirituality through a social justice lens Reimer-Kirkham S. ANS. Advances in nursing science.2014;37(3). CrossRef

- Handmade Patient-Specific Bolus Combined With Photon Radiation Therapy for Skin Cancer Robatjazi M, Jamalabadi SS , Beynabaji S, Baghani HR , Javadinia SA . Case Reports in Oncological Medicine.2025;2025. CrossRef

- Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy for Older Patients with Oligometastases: A Proposed Paradigm by the International Geriatric Radiotherapy Group Nguyen NP , Ali A, Vinh-Hung V, Gorobets O, Chi A, Mazibuko T, Migliore N, et al . Cancers.2022;15(1). CrossRef

- Trends in Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Nursing-A Discursive Paper Timmins F, Attard J, Dobrowolska B, Connolly M, Caldeira S, Parissopoulos S, De Luca E, Whelan J. Journal of Advanced Nursing.2025. CrossRef

- Thai Buddhist patients with cancer undergoing radiation therapy: feelings, coping, and satisfaction with nurse-provided education and support Lundberg P. C., Trichorb K.. Cancer Nursing.2001;24(6). CrossRef

- Buddhism and medical futility Chan TW , Hegney D. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry.2012;9(4). CrossRef

- Relationship Between Religion/Spirituality and the Aggressiveness of Cancer Care: A Scoping Review Santos Carmo BD , Camargos MG , Santos Neto MFD , Paiva BSR , Lucchetti G, Paiva CE . Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.2023;65(5). CrossRef

- Preventive Cancer Screening Among Resettled Refugee Women from Muslim-Majority Countries: A Systematic Review Siddiq H, Alemi Q, Mentes J, Pavlish C, Lee E. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health.2020;22(5). CrossRef

- Role of Nutrition in Pediatric Patients with Cancer Pedretti L, Massa S, Leardini D, Muratore E, Rahman S, Pession A, Esposito S, Masetti R. Nutrients.2023;15(3). CrossRef

- Nutrition in Cancer Patients Ravasco P. Journal of Clinical Medicine.2019;8(8). CrossRef

- The role of religion/spirituality for cancer patients and their caregivers Weaver AJ , Flannelly KJ . Southern Medical Journal.2004;97(12). CrossRef

- Spiritual Well-being Among Palliative Care Patients With Different Religious Affiliations: A Multicenter Korean Study Yoon SJ , Suh S, Kim SH , Park J, Kim YJ , Kang B, Park Y, et al . Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.2018;56(6). CrossRef

- Respectful care of human dignity: how is it perceived by patients and nurses? Aydın Er R, İncedere A, Öztürk S. Journal of Medical Ethics.2018;44(10). CrossRef

- The enigma of doctor-patient relationship Harbishettar V, Krishna K. R., Srinivasa P, Gowda M. Indian Journal of Psychiatry.2019;61(Suppl 4). CrossRef

- Social participation challenges and facilitators among Chinese stroke survivors: a qualitative descriptive study Wan X, Sheung Chan DN , Chun Chau JP , Zhang Y, Gu Z, Xu L. BMC public health.2025;25(1). CrossRef

- Spiritual care provided by Thai nurses in intensive care units Lundberg PC , Kerdonfag P. Journal of Clinical Nursing.2010;19(7-8). CrossRef

- Assessment of spiritual care competency and influencing factors among nurses at the National Institute of Cancer Care, Sri Lanka: a descriptive cross-sectional study Rajapaksha T, Wijesinghe D, Adikari G, Malaweera C, Udari R, Ranaweera N, Amarasekara T. BMJ open.2025;15(7). CrossRef

- Multi-modal intervention for managing symptom cluster of cancer-related fatigue-sleeping problem-depressed mood in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: A pilot randomized controlled trial Wong WM , Sheung Chan DN , Wei So WK . Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing.2024;:11. CrossRef

- 'Global health' and 'global nursing': proposed definitions from The Global Advisory Panel on the Future of Nursing Wilson L , Mendes Ia , Klopper H , Catrambone C , Al-Maaitah R , Norton Me , Hill M . Journal of advanced nursing.2016;72(7). CrossRef

- Chinese values, health and nursing Chen Y. C.. Journal of Advanced Nursing.2001;36(2). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2026

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times